Comments

The theme of the book is life on other worlds. Willy Ley’s “Introduction: Other Life Than Ours” is typically excellent work, clearly yet deeply summarizing what was then known about the possibilities of life elsewhere in the solar system, the chemistry of silicon-based lifeforms, how to determine if an alien world could support life, familiar or not, and the possibility of life originating not on Earth but in spores from outer space, panspermia. He then proceeds to attempt to calculate how many other planets in the galaxy are “on the verge of space travel.”

If that sounds familiar, you’re probably thinking of the much more famous Drake Equation, written in 1961 by astronomer Dr. Frank Drake. Ley proceeds down a virtually identical pathway a full decade earlier.

We can reason like this: Our island universe, our galaxy, contains at least 15 billion suns. … Being as pessimistic as is consistent with good sense we’ll put the number of suns with planets down as one billion, or 1,000,000,000. Each of these can be expected to have at least two planets of the type of Earth and Mars. This gives us two billion planets in our galaxy that can be expected to harbor life.

If we say that just one out of a hundred of these planets has progressed far enough to produce intelligent life of some sort, we arrive at the fantastic figure of twenty million planets with intelligent beings. Again, if only one out of a hundred of these intelligent types have progressed as far in the engineering sciences as we have, we get two hundred thousand planets on the verge of space travel.

And if, again, one out of a hundred is no longer just “at the verge” – but here begins the realm of science fiction.

Maybe we need to start a campaign to relabel it the Ley equation.

Gnome Notes

As usual with Gnome, a fair number of oddities crept into the production of the book. Samuel Anthony Peebles is listed on the Contents page for his preface to a “Science Fiction Dictionary,” but the actual entry is titled “A Dictionary of Science Fiction” and credited to David A. Kyle, Martin Greenberg, and Samuel A. Peeples, that being the correct spelling. The Dictionary covers terms not often seen in the mundane world, from ANDROID, B.E.M., and BLASTER to SPACEOPHONE and VISI-PLATE.

The Contents page deserves a second and third and fourth and fifth look. The pseudonyms Robert Heinlein used early in his career had long been known. Gnome itself had published Sixth Column, originally as by Anson MacDonald, as a Heinlein book without ever mentioning MacDonald. Yet “Columbus Was a Dope,” is credited to Heinlein’s secondary pseudonym of Lyle Monroe, the one he used from 1940-1942 in second- and third-rate markets before rising to the top in Astounding. The Monroe moniker is listed on the Contents page, in the body of the text, and on the spine, yet anything checking the credits on the copyright page would see that it was by “Robert A. Heinlein.” The discrepancy is even odder given the circumstances. Written after WWII, when Heinlein had success selling to major mainstream magazines, the slight, punchline tale had been bounced by all the “slicks” and wound up in Startling Stories under Heinlein’s name. Yet he had had multiple requests to reprint the piece in anthologies. Heinlein assumed that his name was all that others wanted. He told his agent to offer it to Greenberg only under the otherwise long forgotten Monroe pseudonym, the logic being that if he bit he must want the story for itself. In that case, he could use Heinlein’s name. Well, Greenberg did want the story and then didn’t use the valuable name. Did the agent forget to make the offer? Greenberg normally made a fetish of crediting stories as they had first appeared in magazines, so why the glaring exception this time?

Christopher Youd is another less famous name for a famous author, though Greenberg could hardly have known that at the time. Sam Youd (not Samuel) adopted the name Christopher as his confirmation name, and published one poem as C. S. Youd as a teen. “Christmas Tree,” which appeared in the February 1949 Astounding, seems to be the first story Youd published and one of only four under that name. In 1951 he switched to using Samuel Youd for a half dozen novels while simultaneously using John Christopher for short stories. As John Christopher he would gain huge fame for The Death of Grass (No Blade of Grass in the U.S.).

Campbell had a good eye for young authors, but so did Greenberg. Remarkably, there were two other first stories in Travelers, Keith Bennett’s “The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears,” and Robertson Osborne’s “Action on Azura,” both from Planet Stories. That’s Bennett’s only story listed on the ISFDB and one of only two for Osborne, the other as by Richardson Osbourne. Absolutely nothing is known about them. My guess is they were pseudonyms that have slipped by everyone.

Edd Cartier contributed 16 black-and-white illustrations of aliens, which were colorized for the book, with Dave Kyle writing a story about an “Interstellar Zoo” to describe them. The native of Jupiter’s moon Callisto looks remarkably like Chewbacca and is just slightly taller at nine feet.

And then there’s the utter mystery that is the second printing cover. After the printing accident that occurred with his first book, The Carnelian Cube, Greenberg never again acknowledged that any Gnome book went into a second printing. The few which did are usually easily detected when they are placed side by side, although note below. Two of Asimov’s Foundation books were also stripped of one or more of the colors used, a ploy that made printing cheaper. Money was a consideration in most of the other variants as well. Greenberg bound only as many books as he thought he could easily sell and stored the unbound pages for years until he had a need to bind them, thereby lowering his printing costs at the outset. The new boards were whatever the binder had available on the cheap.

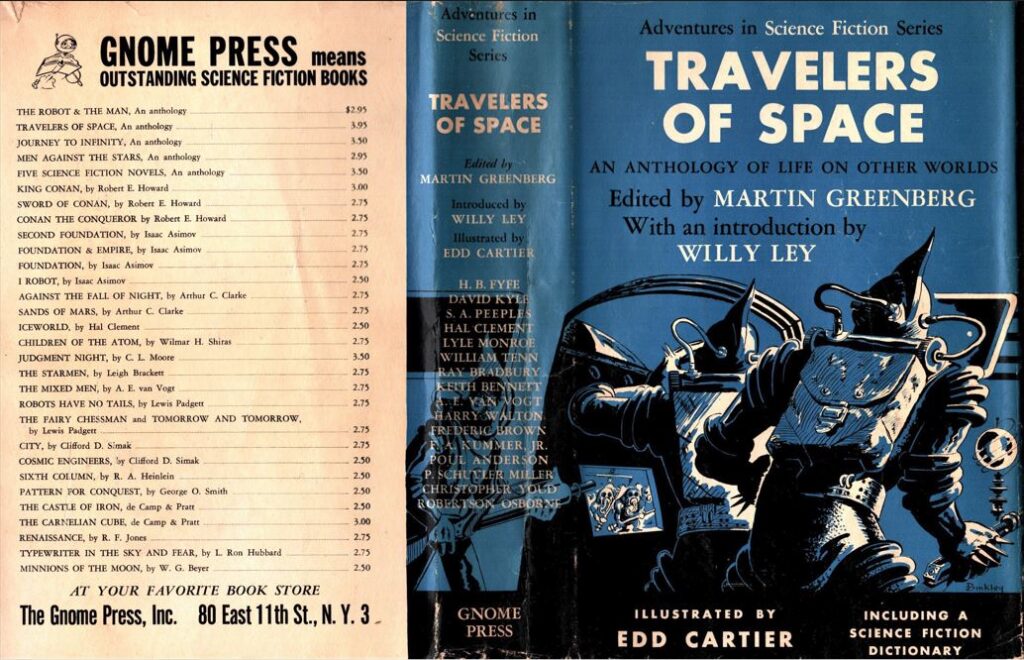

Travelers reverses this norm. ESHBACH lists it as having a true second printing, but the boards and the paper seem identical. Only the cover has changed. For no obvious reason, Greenberg used a Ric Binkley painting to create an entirely new front cover to go along with the new back panel enhanced to list 20[!] new titles released since the first edition. Despite being stuck with a blue one-color overlay, again presumably to save money, the astronauts facing off toward eternity strike these modern eyes as much more intriguing than the stereotypical green aliens on a red and black background that Kyle took from Cartier’s illustrations for the first printing. This is the only time in Gnome history that a totally different variant cover was produced for the standard trade market. The other variant cover, on Murray Leinster’s The Forgotten Planet, is its own unique story.

Or is it? In 1979, collector and dealer Robert Weinberg bought a huge closet-full of leftover Gnome art and dust jackets from Greenberg. Reminiscing decades later, he wrote that Greenberg told him that he had an alternate cover done for Travelers because – just as with Forgotten – librarians thought the original was “too garish.” In retrospect, this seems unlikely. For one thing, if the first printing of 5000 copies sold out, presumably libraries weren’t being overly squeamish. For another, during that period Gnome printed jackets that were equally garish and no complaints are recorded. For a third, not a single newspaper reference before an impossible 1957 comes from a library buying the book that could be from the time the second edition was released.

When exactly was that? That’s not an easy question either. The ISFDB gives the date as 1953. KEMP and CHALKER give 1955. That can’t be right: the titles listed on the rear cover only go through Second Foundation, from May 1953. The Robot and the Man was published as a new title in March 1953 with this back panel and the second printing of Journey to Infinity also uses it, marking them as a set certainly released together. What shakes to the core any certainty I might have is that my copy has a previous owner’s inscription of May 1952. That’s utterly impossible. Possible solutions are that the dust jacket was taken from another copy or that the owner meant 1953 or that time travel was involved. Dating Gnome releases gives me the fantods.

Reviews

Groff Conklin, Galaxy Science Fiction, May 1952

Publisher-Editor Greenberg has given us a really portentous volume here, full of miscellaneous apparati and whammies.

Unsigned, Oakland Tribune, January 27, 1952

A starred Baedecker [sic] guide for the sightseer to other plants [sic] both real and imagined… and a special descriptive piece introducing color illustrations which make Dali look like a sidewalk photographer by comparison.

Clark Kinnard, San Francisco Examiner, February 26, 1952

The future rushes at us with the speed of light. The healthy-minded are aware of our head-long plunge into a strange and different future. The more they speculate about it now, the less terrifying it will be. Science-fiction is a much more significant force than the deductions according to Freud or Jung and the V-neckline, with which the literary Arguses are so preoccupied.

Contents and original publication

• “Foreword,” Martin Greenberg (original to this volume).

• “Introduction: Other Life Than Ours,” Willy Ley (original to this volume).

• “Preface,” Samuel Anthony Peeples (original to this volume).

• “A Dictionary of Science Fiction,” Samuel A. Peeples, David A. Kyle, and Martin Greenberg (original to this volume).

• “The Interstellar Zoo,” David Kyle (original to this volume).

• “Life on Other Worlds,” illustrations by Edd Cartier (original to this volume).

• “The Rocketeers Have Shaggy Ears,” Keith Bennett (Planet Stories, Spring 1950).

• “Christmas Tree,” Christopher Youd (Astounding Science Fiction, February 1949).

• “The Forgiveness of Tenchu Taen,” F. A. Kummer, Jr. (Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1938).

• “Episode on Dhee Minor,” Harry Walton (Astounding Science-Fiction, October 1939).

• “The Shape of Things,” Ray Bradbury (Thrilling Wonder Stories, February 1948).

• “Columbus was a Dope,” Lyle Monroe (Startling Stories, May 1947).

• “Attitude,” Hal Clement (Astounding Science Fiction, September 1943).

• “The Ionian Cycle,” William Tenn (Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1948).

• “Trouble on Tantalus,” P. Schuyler Miller (Astounding Science-Fiction, February 1941).

• “Placet is a Crazy Place,” Fredric Brown (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1946).

• “Action on Azura,” Robertson Osborne (Planet Stories, Fall1949).

• “The Rull,” A. E. van Vogt (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1948).

• “The Double-Dyed Villains,” Poul Anderson (Astounding Science Fiction, September 1949).

• “Bureau of Slick Tricks,” H. B. Fyfe (Astounding Science Fiction, December 1948).

Bibliographic Information

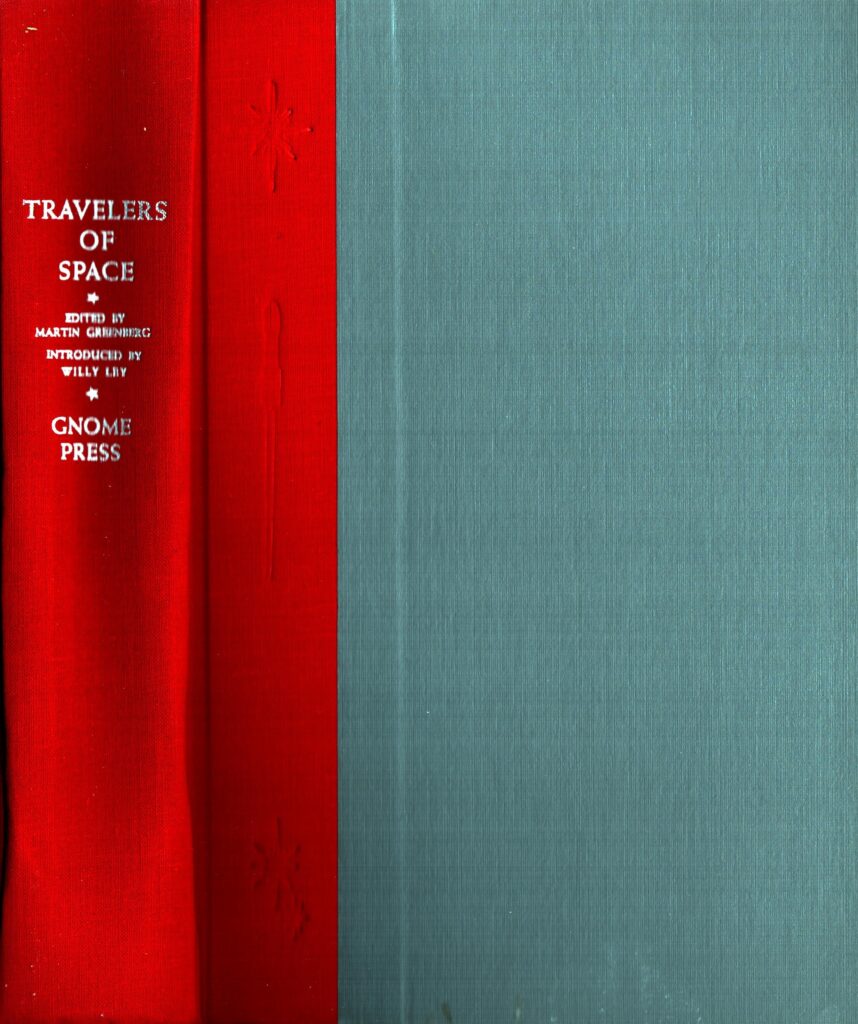

Travelers of Space, Edited by Martin Greenberg, Adventures in Science Fiction Series 3, 1951, copyright registration 3Jan52 [in notice: 1951], Library of Congress Catalog Card Number none [52-6594], title #18, back panels #17,22, 400 pages, $3.95. 5000 copies printed 1951; 2500 printed 1953? Hardback, red cloth-backed spine with gray cloth and silver lettering. Rocket ship traveling between stars embossed into front cloth. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Manufactured in the United States of America. Colonial Press, Inc. Printers. David Kyle, Book Designer.

Variants

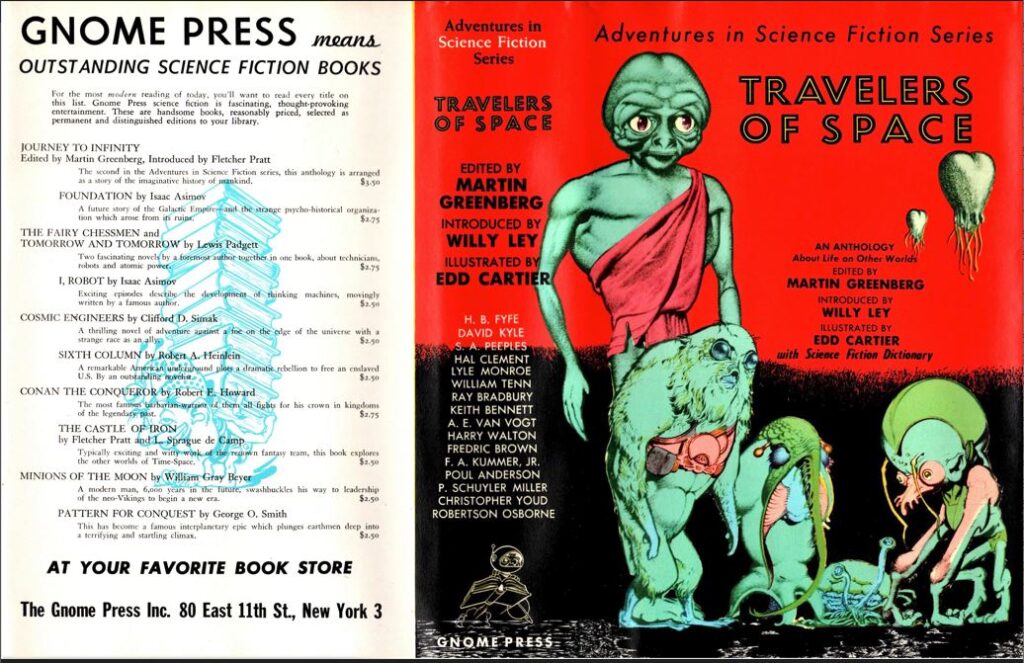

1) Red and black jacket depicting aliens; front flap: Jacket Illustrations by Edd Cartier with Design by David Kyle; Back panel: 10 titles, prose intro. Gnome Press address is given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

2) Blue two-color cover; front flap: Illustrations by Edd Cartier with Jacket Design by Ric Binkley; Back panel: 30 titles, no intro. Gnome Press address is given as 80 East 11th St., N. Y.

Images