Comments

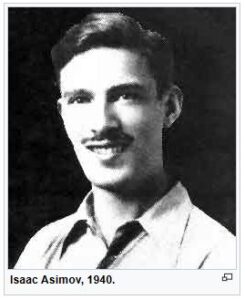

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992)  was born in Russia sometime in 1919, with a birth name of Isaak Iudich Azimov. His records lost, he adopted his family’s anglicized name and gave himself a birthday of January 2, 1920. Asimov worked in his father’s Brooklyn candy store continually from a young age into graduate school and became enamored of the science fiction pulp magazines sold there. When still a pre-teen, the writing bug seized him, although his first professional story did not sell until Raymond Palmer published “Marooned Off Vesta” in the March 1939 Amazing Stories. Only 19, Asimov was almost a college graduate. He’s usually credited with a degree from Columbia College, but, as he often bitterly noted, as a Jew he was barred from registration at the ivy league school proper and relegated to affiliated campuses; he formally graduated from Columbia’s University Extension. Nevertheless, Columbia’s graduate schools had no such prohibitions and he received his Master’s and Doctorate in Chemistry there after WWII.

was born in Russia sometime in 1919, with a birth name of Isaak Iudich Azimov. His records lost, he adopted his family’s anglicized name and gave himself a birthday of January 2, 1920. Asimov worked in his father’s Brooklyn candy store continually from a young age into graduate school and became enamored of the science fiction pulp magazines sold there. When still a pre-teen, the writing bug seized him, although his first professional story did not sell until Raymond Palmer published “Marooned Off Vesta” in the March 1939 Amazing Stories. Only 19, Asimov was almost a college graduate. He’s usually credited with a degree from Columbia College, but, as he often bitterly noted, as a Jew he was barred from registration at the ivy league school proper and relegated to affiliated campuses; he formally graduated from Columbia’s University Extension. Nevertheless, Columbia’s graduate schools had no such prohibitions and he received his Master’s and Doctorate in Chemistry there after WWII.

Even before his first story sold, Asimov made regular visits to John W. Campbell’s office to submit stories to Astounding. Local writers had a tremendous advantage in those days. Campbell would make the time to meet and encourage budding writers. Not only did he sit and talk to them but when they came to pick up a rejected story, he would offer long critiques of their work. After he started buying stories, Campbell would fling ideas at them and bombard them with suggestions that were more like commands. Marty Greenberg used dozens of stories from the core writers Campbell shaped and guided, and was as important to Asimov’s later fame as Campbell was.

In 1939, though, Asimov was a teenager still grappling with basic writing skills. He only sold one story to Campbell before 1941, with his other work going to lesser magazines. Frederik Pohl, only a month older than Asimov, was somehow editing two magazines on a budget very near zero. To fill pages, he relied heavily on marginal work from his friends in the New York science fiction society known as the Futurians, of which Asimov was a member. Campbell had rejected a robot story of Asimov’s back in 1939 and it sat in a drawer until Pohl asked for it. The September 1940 issue of his Super Science Stories ran “Strange Playfellow,” a gentle tale of a girl and her robot caretaker. Asimov was later frank that the idea came from Eando Binder’s “I, Robot,” a cover story in the January 1939 Amazing Stories. “It certainly caught my attention,” Asimov wrote. “Two months after I read it, I began [what got retitled as] ‘Robbie’, about a sympathetic robot, and that was the start of my positronic robot series.”

Asimov had dropped robots as a subject after the initial rejection, but the story’s publication got him thinking again. In late 1940 he wrote two puzzle tales starring the U.S. Robotics and Mechanical Men troubleshooters Donovan and Powell, “Reason” and “Liar,” both of which were snatched up by Campbell. Always looking to build stories on top of stories to make series that kept readers coming back, Campbell noticed that “Strange Playfellow” had included a line about the First Law of Robotics, which makes it impossible for a robot to harm a human being. He told Asimov that implied three laws, since repeated infinitely often.

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Asimov codified these in his fourth robot story, “Runaround,” appearing in the April 1942 Astounding. Note that the contents of I, Robot shifts this story up to second, right after “Robbie,” making it appear as if the Three Laws had been intended all along. The entire timeline is further scrambled to group the Donovan and Powell stories followed by the Susan Calvin stories and ending with the Stephen Byerly stories, more proof that I, Robot is a collection of short stories rather than a novel.

(As a sidenote, Asimov got scooped as the inventor of three laws of robotics. Buried deep in the June 1941 issue of Fantastic Adventures lay “Sidney, the Screwloose Robot,” by William P. McGivern. These should-be immortal lines are spoken to Sidney: “You must be industrious, you must be efficient, you must be useful. Those are the three laws that are to govern your behavior.”)

Gnome Notes

Asimov finished “The Evitable Solution” in early 1950 and mailed Marty Greenberg a copy in June, after it had appeared in the June issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Campbell had rushed the story into print and Greenberg must have felt the same way. The book appeared totally unexpectedly in bookstores without once being mentioned on the cover of another Gnome title even though Greenberg’s practice in those days was to announce all forthcoming books, some of whom never forthcame. The only possible guess for an answer to this Gnome Press mystery is that Greenberg felt that getting an Asimov title out immediately was more valuable than postponing it, damn the schedule and the value of building word-of-mouth.

When did it appear? Asimov wrote that I, Robot was published on December 2, 1950. That’s probably too early. Newspapers normally reported on new titles shortly after their publication, but the first mention I’ve found isn’t until January 7, 1951. That would fit with the copyright registration being December 20, 1950. Perhaps Asimov meant to say something like December 22 or 27 and a number got lopped off accidentally.

I, Robot was not the title of any of Asimov’s stories. Where did it come from? Memories differ. Authors usually provide their own titles, unless publishers demand a change. Yet the middleman between, the author’s agent, handles most of the paperwork. Frederik Pohl, who was Asimov’s agent at the time, shared his memories on his The Way the Future Was blog.

When I handed the manuscript over to Marty, he said, “I don’t have to read this, I’ve already read them all. I’ll write a contract. But I need a title and there isn’t one on the script.”

He was right. No new title occurred to me, but I’d admired the title on an Eando Binder robot story — “I, Robot,” borrowed from the great Robert Graves novel, I, Claudius — and it wouldn’t matter what we put in the contract, because the title could always be changed and titles aren’t copyrightable anyway. So said the contract, and the Binder title just never got changed.

(Pohl drolly notes the irony that the movie titled I, Robot kept nothing at all of Asimov’s most famous book but the title and the Three Laws of Robotics, neither of which were his idea.)

In counterpoint, Asimov gave some history about his relations with Marty Greenberg in I, Asimov: A Memoir:

Martin Greenberg of Gnome Press was a glib young man [actually two years older than Asimov] with a mustache, quite charming, as glib young men often are, but, as I found out in the end, not quite reliable.

However, he seemed willing to publish collections of my old stories and that rather glorified him in my eyes. I put together nine of my robot stories – eight that had appeared in ASF [Astounding Science Fiction] and the first one, which I now restored to its original title of “Robbie.” He published it toward the end of 1950 under the name of I, Robot, a name that Martin himself had suggested. I pointed out that there was a well-known short story by that name by Eando Binder, but Martin shrugged that off….

Greenberg may have done more than shrugged. James Gunn, in Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction, puts the exchange more strongly. “’Fuck Eando Binder,’ Greenberg said.” Could be. Asimov would certainly not use that language in his family-friendly bio.

The two accounts are possibly reconcilable. Pohl may not have mentioned his interim solution to Asimov at the time and when giving Asimov the contract with I, Robot on it, Greenberg may have taken credit for the name. Gunn noted that, “Asimov credit[ed] the title with helping sell the book,” and it was a hit from the beginning, for Greenberg at least.

Back to Asimov:

Virtually all the books Martin published, including mine, have since been recognized as great classics of science fiction and it boggles the mind that Martin had them all.

However, he could not exploit them properly. He had no capital, he could not advertise, had no distribution facilities, no contacts with bookstores, and the result was that he didn’t sell many copies.

In addition, Martin had a peculiarity. He had an unalterable aversion to paying out royalties and, in point of fact, never did. At least, he never paid me. The royalties could never have been very high, but, no matter how small they were, he wouldn’t pay.

He always had excuses, enormous excuses. His partner was sick. His accountant was dying. He had been caught in a tornado. I suggested that I was willing to wait for the money but couldn’t I at least get a statement of sales and earnings so I could keep track of what he owed me? But no, that too seemed to be against his religion.

Whoever thought of the title should have been remembered in Asimov’s will. The title became instantly iconic, the name Asimov the associational word to robot in any quick quiz. He garnered millions from the simple, instantly memorable phrase. Asimov was a major name in the 1940s, of course, but most of his contemporary acclaim came from the Foundation stories. His robot stories were at best a solid second. Impossible as it seems today, not one of the stories in I, Robot was thought major enough to earn cover art.

I, Robot was one of the four trade paperbacks Gnome released. (see The Trade Paperbacks) CURREY states it was done in 1951, but I know of no other evidence for that. CHALKER states “5000 copies printed, hardbound; 2500 additional copies were bound in 1951 as trade paperback “Armed Forces Edition.” KEMP says “Identical Armed Services edition, 1,000 copies bound sold for 35¢.” ESHBACH also gives 1,000 for the trade paperback. Well, maybe. It is much scarcer than the hardback with only single examples occasionally surfacing.

Reviews

Groff Conklin, Galaxy Science Fiction, April 1951

Here is a continuously fascinating book. … Unreservedly recommended.

John S. Harris, St. Louis Post-Dispatch February 9, 1951

It is in such stories as these that the practical value of science fiction, if there is any at all, is found.

unsigned, Startling Stories, May 1951

About the best thing we can say for it is that, although we are left singularly gelid by the whole robot-idea, we found the book excellent reading all the way.

Contents and original publication

• “Introduction” (original to this volume).

• story introductions (original to this volume).

• “Robbie” (Super Science Stories, September 1940 as “Strange Playfellow”).

• “Runaround” (Astounding Science-Fiction, March 1942).

• “Reason” (Astounding Science-Fiction, April 1941).

• “Catch That Rabbit” (Astounding Science Fiction, February 1944).

• “Liar!” (Astounding Science-Fiction, May 1941).

• “Little Lost Robot” (Astounding Science Fiction, March 1947).

• “Escape!” (Astounding Science Fiction, August 1945 as “Paradoxical Escape”).

• “Evidence” (Astounding Science Fiction, September 1946).

• “The Evitable Conflict” (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1950).

Bibliographic information

I, Robot, by Isaac Asimov, 1950, copyright registration 20Dec50, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number not given [retroactively 51-9134], title #11, back panel #11. 253 pages, $2.50. 5000 hardback copies printed, 1950; unknown number of trade paperback copies printed, 1951?. Jacket design by Edd Cartier. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Book Design by David Kyle. Printed in the U.S.A. Back panel: 2 titles. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th Street, New York 3, N. Y.

Variants in order of priority

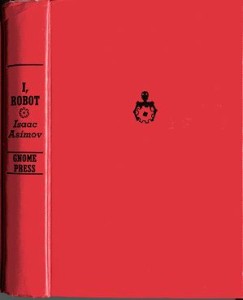

1) Hardback, red cloth, spine lettered in black. Robot holding gearwheel on front cover, gear only on spine.

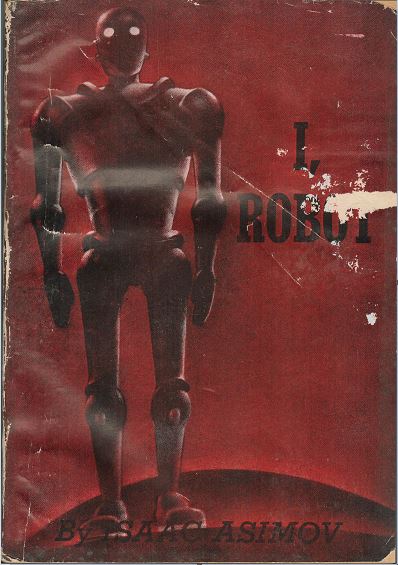

2) Trade paperback, front cover identical to hardback dust jacket, back cover is blank white. Spine reads I, ROBOT by Isaac Asimov in black lettering on white spine. Stated “FIRST EDITION” but is later issue.

Images

— I, Robot, red cloth, black lettering, variant 1

— I, Robot, trade paperback, variant 2