Robert Anson Heinlein (1907-1988) graduated close to the top of the United States Naval Academy in 1929. Although the Academy didn’t confer formal degrees at the time, he received a retroactive Bachelor of Science degree in 1937. By that time, Heinlein had served as a radio and gunnery officer, reached the rank of Lieutenant, and was forced to leave after a lengthy hospitalization for tuberculosis. His later writing shows that this personal crisis and the breakout of WWII would forever haunt him, and he produced multiple stories extoling men in uniforms and demonstrating a fierce patriotism and loyalty to the U.S. government. Unable to serve formally, he moved to Philadelphia to work at the Navy Yard there and recruited Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague de Camp to his team. He also met Navy Lt. Virginia “Ginny” Gerstenfeld, who would become his third wife shortly after the war.

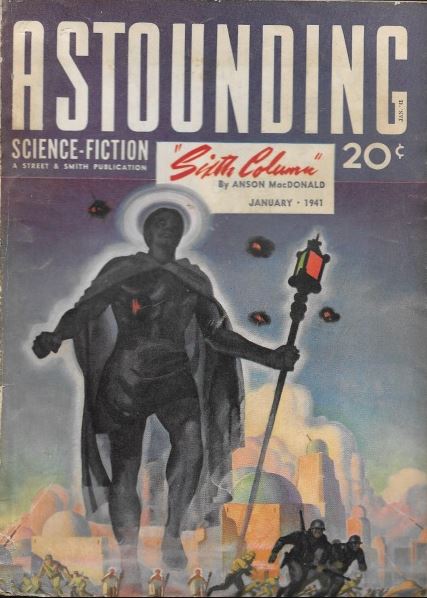

Leaving the Navy made him dependent on his tiny naval pension, and after a short, unhappy fling with left-wing politics (serious enough that the Navy only took him back as a civilian) and many failed jobs, he looked back at his youthful passion for H. G. Wells and tried writing science fiction. His first attempt sold to John W. Campbell’s Astounding in 1939. So did his next couple of dozen. Heinlein was so prolific in his first few years of writing that Campbell had to run some of the stories under pseudonyms so that he could crowd more than one story into an issue. That was the policy in those days; actually, more like a Rule. Presumably the thinking was that readers who didn’t like an author or who wanted the greatest variety in their reading would pass over a table of contents that contained the same name more than once. It was true throughout the pulp era and into the 1950s that some editors ran their magazines on the cheap, filling whole issues with single authors writing tripe at red-hot speed. Hard to imagine that Campbell, helming the best magazine on the market, would be suspected of pawning off such inferior stories, though. Like so many things in the publishing industry, editors just knew what readers would or wouldn’t accept and hewed to those precepts with rigid adherence. In any case, Heinlein had fourteen appearances (including two three-part serials) in Astounding in 1941, competing against himself six times. Perhaps even more surprising, Campbell packed those into eight issues. Why he left Heinlein out of four issues, never used his name again until after the war, invented a second pseudonym, Caleb Saunders (for “Elsewhen” in the September 1941 issue), published only stories as by Anson MacDonald in 1942, and used yet another pseudonym, John Riverside, for his appearance in the Campbell-edited Unknown for “The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag” seems deeply odd at this remove.

Of all the rocket-like rises to stardom of Campbell authors in the prewar years, Heinlein’s was steepest and fastest. He was the Guest of Honor at the third Worldcon, held appropriately on July 4, 1941, after only fabled artist Frank R. Paul and E. E. “Doc” Smith. He lived in Los Angeles, far from the center of the sf world, and yet gathered a group of professionals in the jokingly-titled Mañana Literary Society (i.e, I’ll start working on that tomorrow) equal to those of the later Hydra Club. Gnome author members included Arthur K. Barnes, Leigh Brackett, L. Sprague de Camp, L. Ron Hubbard, Henry Kuttner, C. L. Moore, and Jack Williamson, and others attending were Brackett’s husband Edmond R. Hamilton, Astounding stalwart Cleve Cartmill, wannabe writer Ray Bradbury, and all-everything Anthony Boucher. Under the pseudonym H. H. Holmes, Boucher wrote a mystery titled Rocket to the Morgue (published 1942, set in 1941) using very thinly disguised versions of Society members and featuring probably the first murder plot where the death implement was a rocket ship. Often reprinted under Boucher’s name, the novel is surely the best internal look at the tiny world of 1940s science fiction writers we’re ever going to get. He described the character based on Heinlein as “the biggest name in all Stuart’s [John W. Campbell’s] stable of writers. In fact, I think he’s three of the biggest names.” He had been selling for just over two years at the time Boucher wrote the book.

Were readers in on the joke of Heinlein’s pseudonyms? The fandom in-crowd knew almost as soon as the ink was dry on the page. All the way over in England, the Futurian War Digest shouted the news about MacDonald in its June 1941 issue, though the Sands of Time still thought the announcement, “At long last the news has been released in USA so we might as well tell you that both Anson MacDonald and Lyle Monroe are pseudonyms of Robert Heinlein,” was big news in its March 1942 issue. American fanzines obviously had the news sooner than mail reaching Britain during WWII. Some must have had suspicions when such classic Heinleinisms as “Solution Unsatisfactory” and “By His Bootstraps” appeared under the name Anson MacDonald in the May and October 1942 Astoundings. It’s harder to see how anyone would have guessed it earlier that year, when “Sixth Column” was the first MacDonald signed story, serialized in the January, February, and March 1941 issues and after only seven previous Heinlein stories. Sam Moskowitz, in Seekers of Tomorrow, calls the pseudonym “one of the poorest kept secrets in science fiction” but adds “among the general readers, it may have understandably seemed that an important new talent had appeared on the science-fiction horizon.” Campbell treated Heinlein and MacDonald as separate writers when talking about what was forthcoming – except once, when he assigned “Gulf” to Heinlein but ran it as MacDonald. If fans didn’t know, their heads must have exploded when Fantasy Press published Beyond This Horizon, another MacDonald serial, in 1948 and this book appeared under Heinlein’s name in 1949 without as much as a mention of MacDonald or Astounding.

Gnome Notes

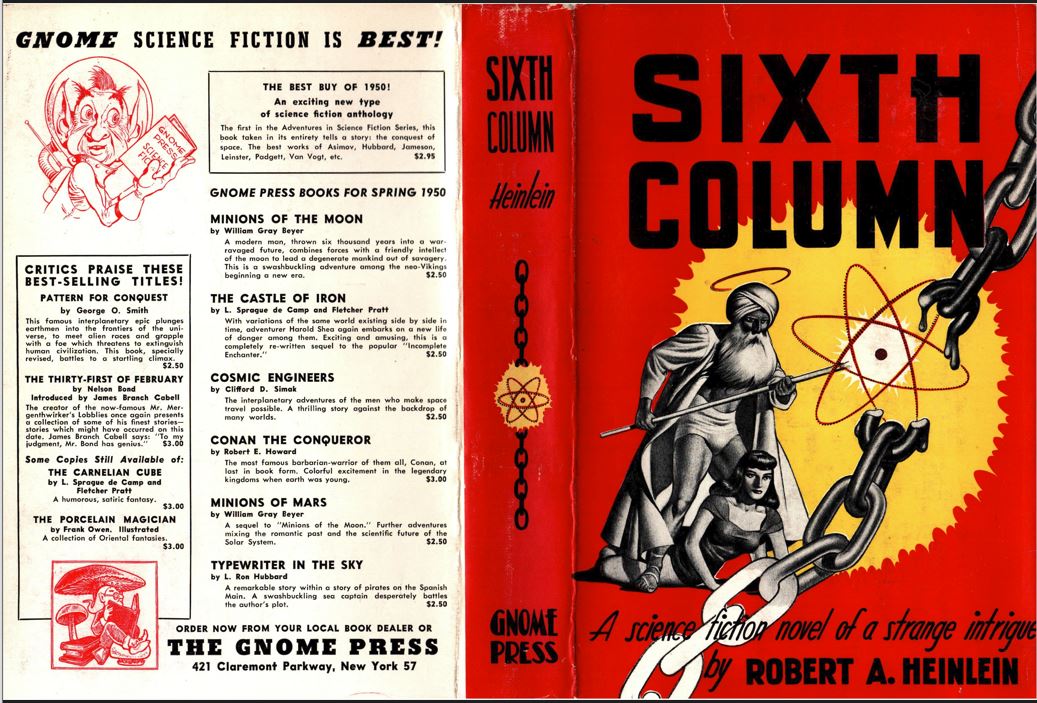

The exact publication date of Sixth is hard to pin down. The copyright registration is from December 7, 1949 but they preceded publication by about a month in these early days. When the Library of Congress assigned Catalog Card Numbers long after the fact it gave Sixth 50-5003, which presumably implies that it came after Pattern for Conquest, which got 50-3818, and before Men Against the Stars, which got 50-6637. Judging by a January 2, 1950 newspaper report that the Tampa library already had Pattern on its shelves, it must have been released in 1949, though probably late in the year. The first mention of Sixth comes in a review column of new science fiction books on January 14, one that also includes Pattern. That’s so early in the year that either a 1949 or 1950 date can be supported.

An obscure, possibly self-published, book on the French Resistance was released earlier in 1949 and was also titled Sixth Column. Since fifth columnists were spies, making resistance forces a sixth column occurred to multiple people, although the term never caught on widely.

Heinlein revised the original for Gnome, the world having changed since 1941. In a 1973 letter, he said, “It was a hard story to write, as I tried to make this notion plausible to the reader – and to remove the racism which was almost inherent to his story line.” Unfortunately, in that same letter he also explained that he incorporated a notion from a British science journal “that the subraces of h. sapiens might be told apart by spectral analysis of blood.” The world that Gnome inhabited can never live up to modern standards. It must be considered historically, almost anthropologically. Even so, Sixth is a low point.

— cover art by Hubert Rogers

Reviews

August Derleth, Madison Capitol Times, February 24, 1950.

[B]etter than average science fiction.

Forrest J. Ackerman, Other Worlds Science Stories, September 1950.

I am saying run, do not walk, to the nearest bookstore or dealer’s ad and be good to yourself by buying a copy of Sixth Column for your favorite shelf.

Contents and original publication

- Chapters 1-12 (rewritten from Astounding Science-Fiction, January, February, and March 1941, as by Anson MacDonald).

Bibliographic information

Sixth Column, by Robert A. Heinlein, 1949, copyright registration 7Dec49, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number [retroactively 50- 5003], title #5, back panel #5, 256 pages, $2.50. 5000 copies printed. Hardback, black cloth, spine lettered in red. Red atomic symbol trailing chains to each side on front cover. Jacket design by Edd Cartier. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Manufactured in the United States of America. No designated printer. Title page, jacket, and copyright registration add “A science fiction novel of a strange intrigue.” Back panel: 10 titles plus “The Best Buy of 1950″ untitled. Gnome Press address given as 421 Claremont Parkway, New York 57.

Variants

None known.

Images