Paper ruled the world of communication back in the 1940s and 1950s. For sure, some business could be done over the telephone, although long-distance charges were horrendous by today’s standards, and sending a telegraph might be justified in certain cases. The far-flung world of science-fiction writers made face-to-face meetings rare and arduous, even when many of them lived in New York. As a result, the filing cabinet industry thrived on the masses of paper generated by every business. Greenberg and Kyle, true to form, threw off mountains of paper consequential to running a business that consisted of nothing more than selling decorated paper.

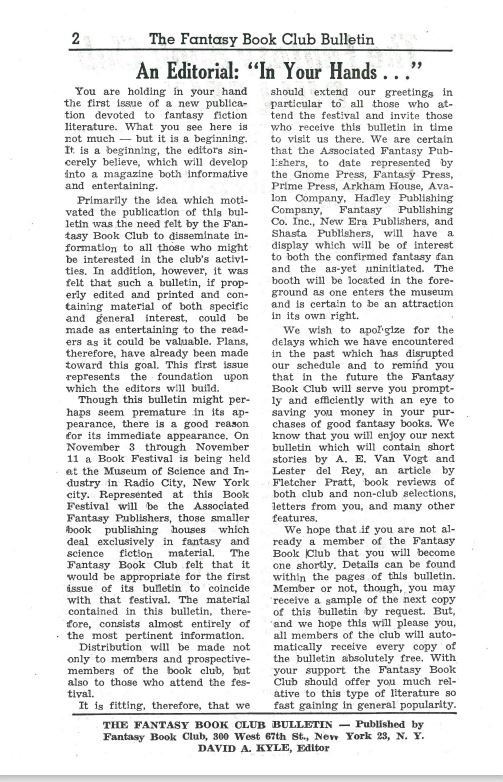

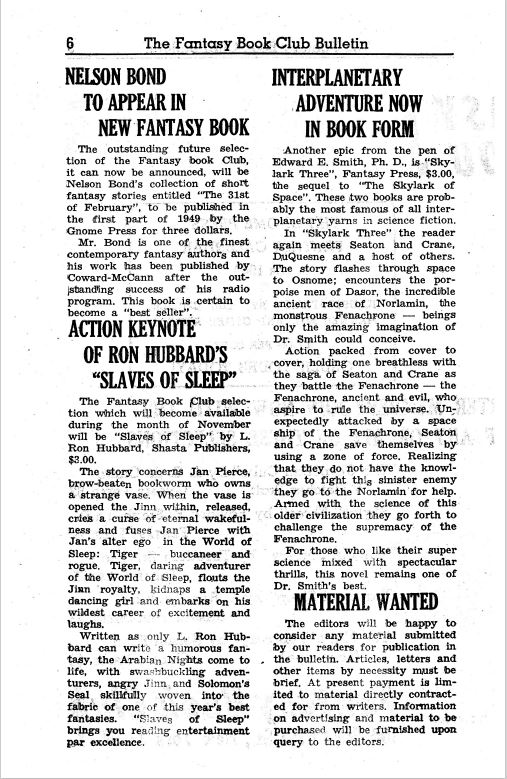

The Fantasy Book Club Bulletin

Gnome’s first piece of ephemera were the 1949 Fantasy Calendar (see The Fantasy Calendars) and the Fantasy Book Club (FBC) Bulletin. ESHBACH says that in:

November 1948 a Fantasy Book Club “Bulletin” was published as a sort of miniature news magazine about the club, its selections and items of general interest. … The FBC continued limping along for several years, but it was never really successful. … Conceived primarily to sell Gnome Press books, it used selections from other publishers as well, purchased as I recall it, at a 50% discount. They made special offers including premiums, and they did sell books. Whether the club created new customers or simply deprived the other specialist publishers of direct sales is an open question.

Not much in that paragraph is true, except the most basic, obvious information. As with virtually all book clubs, the FBC offered premiums, one for every two books purchased, and included a small selection of books from other publishers. Beyond that is failed memory. Neither the FBC nor the Bulletin limped along for several years; they barely lasted longer than a mayfly. CHALKER says that two issues of the Bulletin were produced, but I know of no evidence for that second one. Even the first one continues to be one of the scarcest items of memorabilia. I used to say that they existed nowhere outside a couple of fanzine collections in institutions, until I found one for sale.

It was printed on four sheets of standard 8.5″ x 11″ paper, folded in half to make eight pages. As can be seen on the last image below, the torn stamp at top and bottom presumably means the Bulletin was folded in half again and sealed with a one cent stamp for mailing. These nice bright images come from Fanac.org and somehow do not seem to have that fold visible. My copy, much darkened, was not mailed out and so has neither the stamp nor the addressee nor Dave Kyle’s signature nor the fold.

Review Slips

Announcing the publication of a small press title in the days after WWII required not merely intense work on the part of the publisher but a network of correspondents on the receiving end to make readers aware of forthcoming titles. Throughout the 1940s, book review columns were almost exclusively found in fanzines rather than professional magazines. Fans of the era were almost manically fervent in spreading the word about books, but they had tiny circulations and irregular schedules. The pro magazine boom of the early 1950s corrected this fault with a number of regular review columns that reached virtually everyone in the core f&sf reading community. Very few mainstream publications had a column dedicated to f&sf. The New York Times Book Review and the Saturday Review had occasional columns; only the Capitol Times of Madison, WI, had one that more frequently appeared, written by August Derleth, the founder of Arkham House.

Gnome undoubtedly reached out to all the likely suspects, not a task that would cut greatly into sales: at no time in its existence were there even a dozen professional book review columns running at one time. No evidence of advance review copies has ever surfaced, nor am I aware of any galleys of Gnome titles extant, although we know they were produced. Presumably all the books sent out were standard review copies.

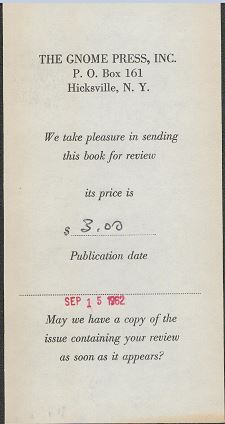

At some unknown point in Gnome’s lifetime, review slips started being included in review copies. Amazingly, a few exist today and the lucky collector will find one unexpectedly in a purchase. That’s happened to me more than once.

The first was inserted into Groff Conklin’s Science Fiction Terror Tales, which had a copyright registration date of February 15, 1955. Sending out the printed book a month later is what you would expect. The off-center printing on the slip may be a clue that many slips were printed onto a single sheet and cut apart as necessary.

The second was in the enigmatic The Philosophical Corps by E. B. Cole, whose date of release has been a mystery for 60 years. The copyright date is December 10, 1962. The publication date given on the slip is September 15, 1962. Before one leaps to the conclusion that here’s an exception to the rule of no advance copies, a newspaper archive search finds that the book was added to the shelves of the Moline [IL] Public Library on June 15, 1962. Indubitably, the library received a standard first edition.

I know of slips for Sands of Mars, The Complete Book of Outer Space, and The Menace from Earth. More surely exist.

Gnome Correspondence

Forget the Atomic Era. In the mundane world, people lived in the Typewriter Era. Every business created paper relics by the score each day. Gnome’s Greenberg and Kyle, and later its assistants, wrote to their writers and artists, to book stores and reviewers, to fans and pros, to printers and distributors, to lawyers and accountants.

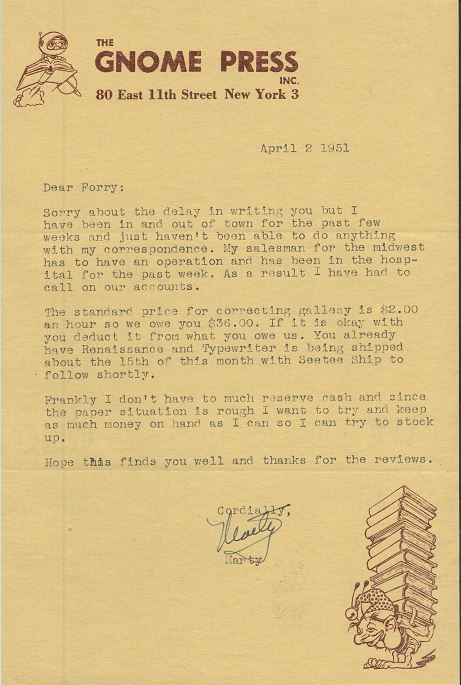

I have two examples in my collection. The first is a 1951 letter from Greenberg to superfan, reviewer, collector, etc. Forry Ackerman, which shows he was being paid to proofread galleys for Gnome, and that therefore galleys existed and might someday be found.

The second is a letter to a fan who wrote in about the Pick-A-Book program.

Serendipitously, this letter contains valuable information about Gnome titles.

In the case of The Shrouded Planet a lot of new material has been added and in Earthman’s Burden we added a new story. We realize the problems of the steady readers of the magazines and try to do this (addition of material) in most books we publish. Methuselah’s Children as an example has been completely rewritten.

That it had been rewritten is a fact given nowhere on or inside Methuselah’s Children. Only the 1959 Pick-A-Book catalog mentions that the book is expanded; no alterations appear in any other catalog or ad. The letter also reveals that Greenberg was writing his own correspondence in 1958, rather than fobbing it off to a secretary or assistant. That was a return to the early days of 1951 before he could afford one: the upside-down U-shaped curve of Gnome’s finances in two letters. The 1958 is standard letter-sized paper, but the 1951 version is only 6.1 x 9.2″. Perhaps this also is an indication of the ways Greenberg pinched pennies to get the firm started.

What catches the eye in the 1958 letter, of course, is not the text but the beautiful letterhead. Drawn by Hannes Bok, it was apparently work that had been paid for but unused until Greenberg found a way to repurpose it, make his business shine, and save the cost of commissioning new work all at the same time.

Many more Greenberg letters still exist. Ackerman kept a bunch of Greenberg letters that my item somehow escaped from. They are probably heading for an institution. Kyle’s small number of known letters is odd for the open market, but again, they appear in institutional collections.

The Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries, contains a box labeled Gnome Press Records.

The Gnome Press Records consist of correspondence, one subject file, production material, publicity material, and published material. Correspondence contains incoming and outgoing correspondence, arranged together chronologically. Subject files consists of a single file of blank contract forms. Production material contains book jackets, correspondence, financial papers, and blank forms. Publicity material consists of advertising brochures. Published material contains a single book.

See The History of Gnome for more details on the printer proposals. Those were sent to Kyle. Some of Greenberg’s letters offer fascinating looks at an alternate history, like a 1950 letter to Fletcher Pratt that read, “A Voice Across the Years would be a fine book if rewritten slightly.” Greenberg offered a $500 advance but I can find no evidence that this ancient 1932 story was ever reprinted by anyone.

Other boxes at Syracuse include papers donated by Gnome writers, although only a few letters actually refer to Gnome. Most, like those of Murray Leinster, pleaded for money. Frederik Pohl, agent for many Gnome writers, wrote stronger and stronger messages, as Greenberg seemed unable to do the smallest things.

I will remind you one more time, and then I will start detesting you. For Christ’s sake, send copies of anthologies to the authors represented so that they won’t think they are being swindled, even if they are.

Other letters from Pohl remind us that pushing science fiction was like rolling huge boulders up hills in the publishing world of 1951.

I guess you know that Mac Talley is bouncing “I, Robot” until “we know a little more about what large numbers of non-science-fiction newsstand buyers will take to under the very general heading of science fiction.”

(Truman Macdonald Talley was a young Associate Editor at New American Library at the time. He spent his life in publishing, becoming part of Weybright & Talley, which printed some notable science fiction, and then creating his own imprints. Victor Weybright started NAL and Talley was his young assistant. And Weybright’s stepbrother. [Wikipedia says stepson. Wrong. Talley’s mother married Victor’s father.] Lest you think only the f&sf publishing world was small.)

The Weinberg Diaspora

Robert Weinberg was another of the multi-hyphenates the field depends on. Fan, convention chair, writer, historian, publisher, collector, dealer, and anthologist with the Other Marty, Martin H. Greenberg, he left not a facet untouched. In 2011, he started writing reminiscences about his activities, including an article about his dealings with Marty Greenberg. From it we hear about vast troves of Gnome items, which were bought from Greenberg and sold to collectors in the 1970s and 1980s. A few tidbits.

Gerry [de la Ree] had bought the cover paintings for the seven Conan books published by Gnome Press, as well as the cover art for I Robot and the Foundation series, all by Isaac Asimov.

I was the only person who had ever asked him [Greenberg] about [dust] jackets and he had hundreds of unused ones. Would I care to make an offer? … Greenberg, I learned, had four hundred unused jackets. I bought them all. They were a terrific investment and I did quite well selling them.

It took me several months to buy almost all the pieces Martin Greenberg still owned. There were color sketches done for the covers, finished paintings, and even some black and white interiors available from several of the books. I took just about everything, negotiating prices that both Greenberg and I felt were fair. The pieces I bought included:

Cover Painting for Undersea Fleet

Cover painting for Undersea City

Cover painting for Undersea Quest

Cover painting for Northwest of Earth

Unused endpapers painting for Gnome juveniles by Ed Emsh

Cover painting for Men Against the Stars by Edd Cartier

Cover painting for SF Terror Tales

12 black-and-whites for the Interplanetary Zoo – art by Edd Cartier

Preliminary painting for Seetee Ship by Cartier

Preliminary painting for Iceworld by Rick Binkley

Preliminary painting for Judgment Night by Kelly Freas

6 Hannes Bok sketches for possible Gnome insignia…

and miscellaneous color proofs and cover sketches.

Among the art souvenirs, I bought one of the few copies of the jacket for the C.L. Moore collection, Northwest of Earth, that was alternately titled Northwest Smith of Earth. Greenberg later decided to drop the Smith because it made the title too long.

— TangentOnline.com, January 31, 2011

These jaw-dropping collectibles must still mostly be out in the world somewhere, in many collections, unpublicized and unknown to the public. I don’t follow art auctions the way I do book auctions, so I may have missed sales. Edd Cartier’s work is a prized and pricey collectible today, so his Gnome work could bring a fortune.

Marty Greenberg’s Estate

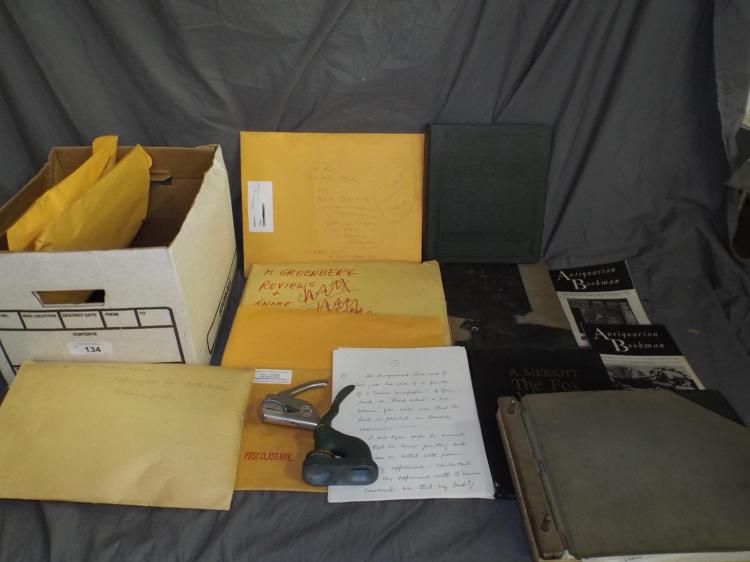

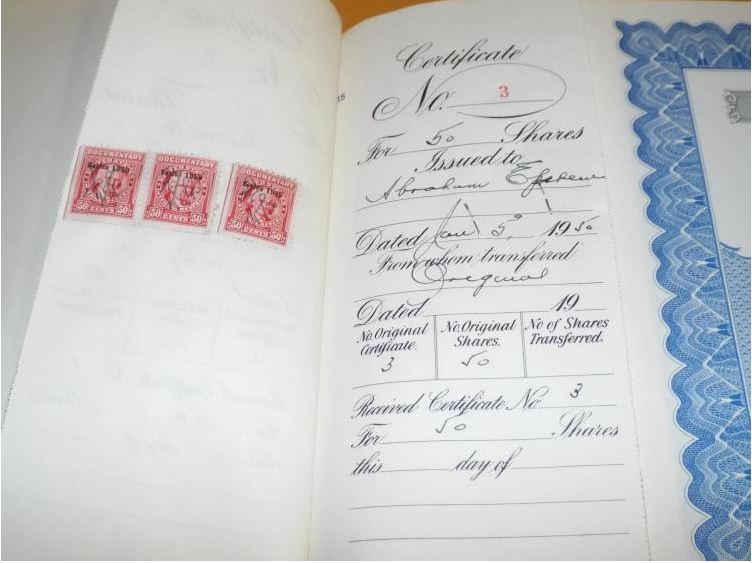

On February 15, 2015, Weiss Auctions presented a trove that is for paper what Weinberg is for art.

Description: Lot includes Original Corporate Seals, Books and Ledgers, Signed Stock Certificate issuing the first 50 shares, Correspondance with Authors and Companies ordering books, 20+ unused Gnome Press Dust Jackets, a wonderful collection for theScience Fiction Historian or Researcher. From the Estate of Gnome Press Publisher Martin Greenberg. [cut and pasted from the original]

The auction consisted of much more than these few images convey. Does the lot still exist somewhere? Was it tossed as worthless relics of a forgotten past? Can it still be stored in someone’s attic? We can only hope.

Wait! There’s More

Odds and ends of Gnomeiana, a coinage that I hope does not catch on, continue to pop up.

As weirdly mysterious as many other Gnome puzzles is the story behind the Conan endpaper. In the 1930s, Robert E. Howard sketched out several maps of the quasi-Europe/African continent in which he set his Conan stories. Dave Kyle took the maps and elaborated it with provincial names, mountain ranges, wavy oceans, and fancier ships, and called it “The World of Conan in the Hyborean Age.” (Why he misspelled or respelled Hyborian isn’t known, but the spelling was used consistently for the first five Gnome Conans, until it was belatedly changed.) Browsing through a dealer’s box of ephemera at a 2019 convention, I found a copy of the map, signed by Kyle. It has a larger border than do the endpapers, but seems to be of the same paper stock. It can confidently be dated to the 1950 first appearance, in Conan the Conqueror, because all later appearances were in different colored ink. As far as I know, this is the first mention of such a prize in print so no other information about it can be offered. Did Kyle pull a few endpapers before they were cut to size? Was this a separate run? Who were these given to? Was there ever more than one? An exceptional Gnome mystery.

Weinberg’s buyers are not the only ones to have a crisp new dust jacket. For reasons unimaginable, my copy of Plague Ship came covered by two dust jackets. Naturally, the inner one, untouched by light over the decades, is especially bright. (Although the other cover rivals it, apparently stored properly away by someone who appreciated what they had. My Gnome collection occupies a large bookcase in an inner hallway with no windows.) The book is the rare tan boards variant, bought for that purpose despite its being in terrible condition. Odd to think that perhaps my worst boards are covered by perhaps the best dust jacket.

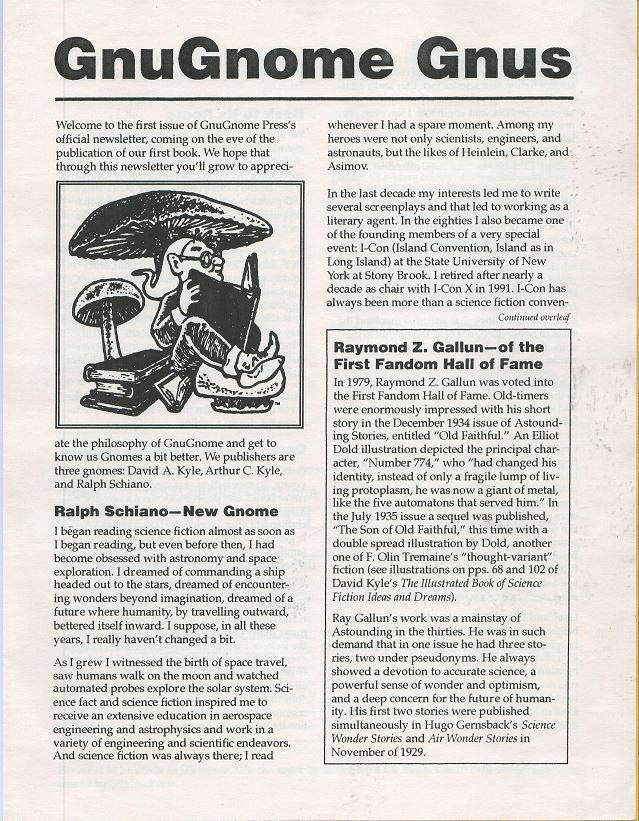

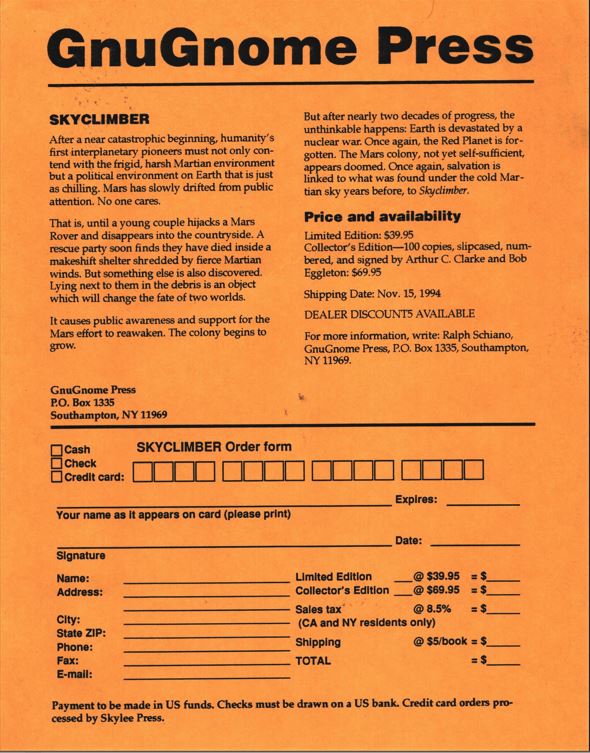

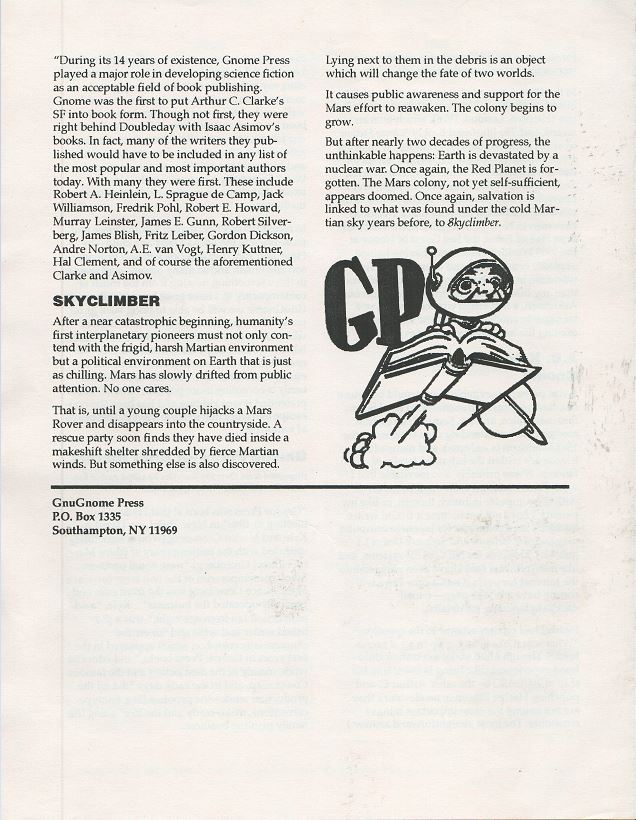

In 1994, Dave Kyle, with some assistance, made yet another in a string of attempts to relaunch Gnome Press, this time as GnuGnome Press – gnu being a fannish spelling of “new”. Oh, the chortles they had. The first issue from GnuGnome was to be a hardback reprint of Raymond Z. Gallun’s 1981 paperback Skyclimber. Sadly, Gallun died just as the venture was announced, leaving only a newsletter and order form behind.

Wait, There’s More?

I’ve referenced all the ephemera that I know about, either from my collection, from institutional collections personally visited, from images online, or from writings detailing holdings. There must be more. Other institutions have letters from other Gnome writers that may provide Gnome information. Fanzine collections in or out of institutions may have untapped information that has not been scanned by fanac.org or efanzines.com. Dealers may have boxes of unsorted ephemera that could be gone through and put online for sale.

Most especially, other collectors must surely have their own troves of treasured items. Nobody knew about the many items in my collection until I put them online here. I hope that with this website, all manners of hidden Gnomeiana (Blast, there’s that word again) will surface. Please get in touch with me using the comment field about ephemera or any other Gnome topic. If you want to remain anonymous I will strictly adhere to your wishes.

Thank you for reading to the end. I started work on making this the ultimate Gnome resource a full decade ago. The more work I did, the more work proved necessary to research and add. With so many mysteries and missing pieces, the history of Gnome can never be truly complete without a very intrusive time machine. Calling this site the Complete History and Bibliography is therefore a bit of hubris. Putting it on the web for easy correction will make it ever more Completer. (Remember that James Fixx followed The Complete Book of Running with the all-new Jim Fixx’s Second Book of Running.) I hope that with your help, I’ll be busy adding more and better information for many years to come.

April 15, 2024.