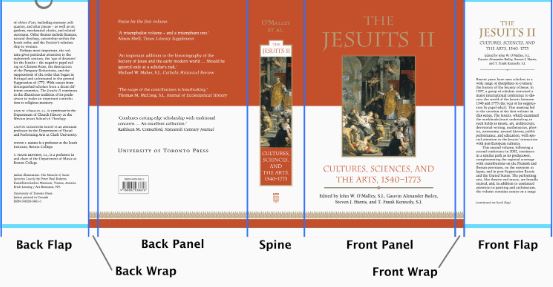

Dust jackets, unlike Gaul, are divided into five parts. From left to right they are the back flap, the back panel, the spine, the front panel, and the front flap. (Purists and printers may want to add a back wrap and a front wrap to account for the tiny sections that wrap around the boards.) Each area is valuable real restate. Rare is the book which leaves any of the five blank. The front panel, familiarly known as the cover, is a billboard for the book, an advertisement of the author and the title set in what is usually a colored background of art, photography, or typography meant to catch the eye and entice potential buyers’ interests. The front flap is the equivalent of a press release, many hundreds of extravagant words that extol the book, the author, or the subject, whichever is most likely to lead to a sale. The rear flap might continue the sales pitch, add a photograph of the author, or tout other books by the publisher.

For most books today, the back panel contains gassy blurbs by friends of the author or a precis of the contents or a short bio or a photograph or any combination of these. Nobody really knows what sells a book; publishers throw tantalizing tidbits at the page and hope that some work much the same way that menus offer pasta, chicken, and steak and presume that at least one from the variety will appeal to all tastes.

The small f&sf presses in the 1940s and 1950s had a more complex problem. In addition to selling a specific book, they also needed to sell themselves. They did not employ squadrons of salespeople, as the large mainstream presses did. They had small to nonexistent advertising budgets. They had little expectation at first that libraries would automatically buy their books, for the field was generally considered sub-literary, a bastion of pulp hacks and juvenile illiterates. They had to educate buyers to form new habits, for the simple reason that virtually no hardcover f&sf titles had ever been published before World War II. Booksellers needed to be taught to look for the catalogs and announcements that the presses put forward and to create new sections in their stores. Libraries had to be convinced that these books were worthy to sit alongside the famous names of mainstream fiction. Individual buyers had to learn that such books now existed, and be persuaded to pay the price of a hardcover book for material they were more accustomed to seeing in cheap magazines. And all of this effort had to be put forth for no more than a tiny niche of the overall book market, whose collective total of readers undoubtedly numbered less than the buyers of a single bestseller.

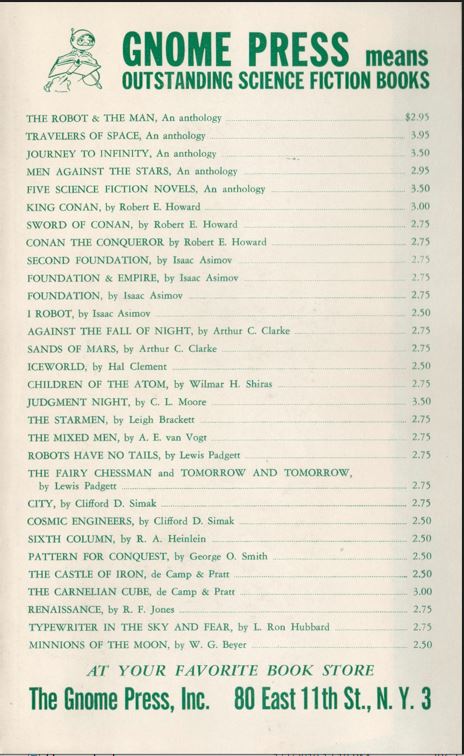

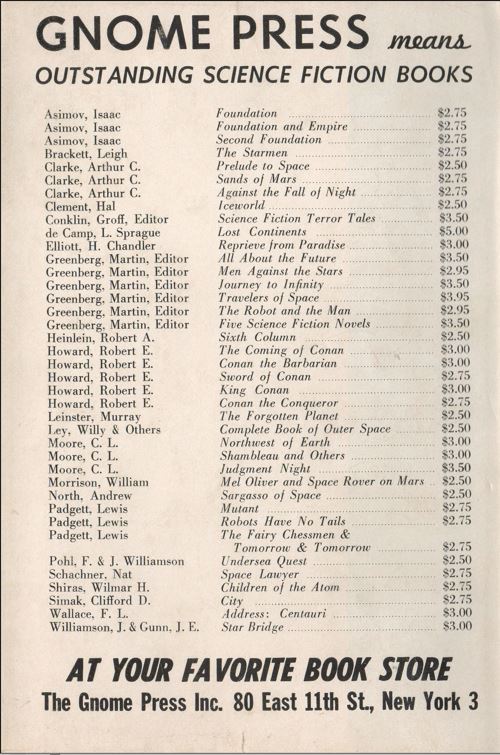

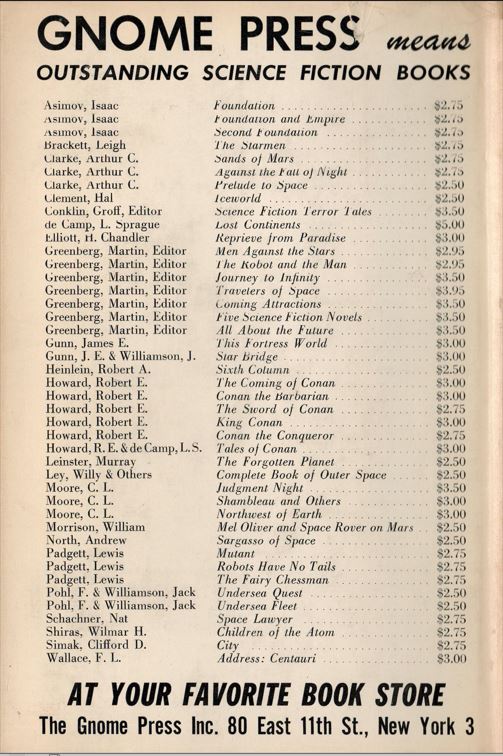

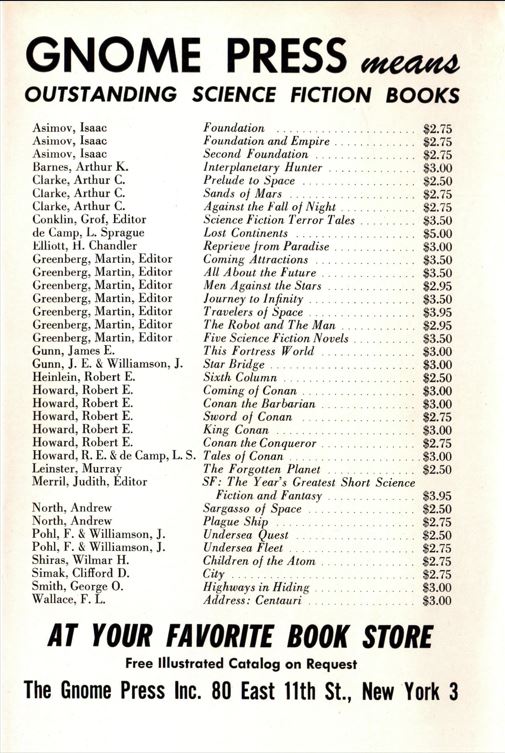

Small presses quickly learned – or simply assumed – that the best and highest use of a back panel was not to tout the author or the book but to advertise the publisher. The cover and flaps sold the current book; the back panel sold all the other books by the publisher. Anticipating Amazon, back panels grew into ever longer lists of titles, implying that if you liked the book in your hands you would be equally delighted with any of these similar books by the publisher, someone who understood and anticipated your tastes.

Marty Greenberg could look at the back panels from other presses for inspiration. (For convenience I will be using Greenberg’s name as shorthand for the unknown hands who were actually responsible for the copy over the years.) Arkham House, the pioneer, had been publishing for a decade before Gnome. The back panel for Ray Bradbury’s collection, Dark Carnival, proudly listed sixteen titles as “Ready,” available to buy. Under those were six titles “Coming in 1947.” Those must have engendered the same anticipation that a trailer for a new superhero blockbuster does today. That three of the books slipped to 1948 and one title never appeared at all doesn’t lessen the importance of such coming attractions, although it should have served as a reminder to both publishers and readers that the future is always uncertain and those of small presses especially chancy. Greenberg would stumble over this reality more than once.

Gnome used 41 different back panels for its 86 titles. I’ll display and discuss each of them in order of the release dates I discussed in the last chapter. Later variant back panels on reprints or rebindings will be inserted in the timestream as appropriate, thereby giving valuable information on their release dates. Much of the discussion will examine whether the ordering is substantiated by the titles listed – and just as importantly, not listed – on the back panels. The following information will be displayed under each back panel image:

Back Panel: My assigned numbering of unique back panels used by Gnome as given in Table 1.

Title(s) on: Title(s) of books using this unique back panel.

Titles displayed: Publishing order of titles on back panels as given in Table 1.

Forthcoming: Not yet published titles with that designation.

Title(s) on back flap: New publishing order of titles as given in Table 1, if any. (Titles not given if repeated from back panel.)

Missing: New publishing order of already published title as given in Table 1 if not listed on either back panel or back flap; titles not listed on their own back panel are not considered missing.

| New | Old | Back Cover | Author | Title | Short Title | Pub. date | Copyright | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | L. Sprague de Camp & Fletcher Pratt | The Carnelian Cube | Carnelian | 1948 | 11/1/1948 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | Frank Owen | The Porcelain Magician | Porcelain | 1948 | 2/20/1949 | |||

| 3 | 5 | 3 | Nelson Bond | The Thirty-first of February | February | 1949 | 6/18/1949 | |||

| 4 | 3 | 4 | George O. Smith | Pattern for Conquest | Pattern | 1949 | 11/16/1949 | |||

| 5 | 4 | 5 | Robert A. Heinlein | Sixth Column | Sixth | 1949 | 12/7/1949 | |||

| 6 | 6 | 6,19 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | Men Against the Stars | Men | 1950 | 3/20/1950 | |||

| 7 | 7 | 7 | L. Sprague de Camp & Fletcher Pratt | Castle of Iron, The | Castle | 1950 | 7/1/1950 | |||

| 8 | 8 | 8 | William Gray Beyer | Minions of the Moon | Minions | 1950 | 7/15/1950 | |||

| 9 | 9 | 9 | Robert E. Howard | Conan the Conqueror | Conqueror | 1950 | 10/17/1950 | |||

| 10 | 11 | 10 | Clifford D. Simak | Cosmic Engineers | Cosmic | 1950 | 11/25/1950 | |||

| 11 | 10 | 11 | Isaac Asimov | I, Robot | I, Robot | 1950 | 12/20/1950 | |||

| 12 | 17 | 12,21 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | Journey to Infinity | Journey | 1951 | 1/3/1951 | |||

| 13 | 14 | 13 | Raymond F. Jones | Renaissance | Renaissance | 1951 | 4/15/1951 | |||

| 14 | 15 | 14 | L. Ron Hubbard | Typewriter in the Sky and Fear | Typewriter | 1951 | 5/15/1951 | |||

| 15 | 12 | 15 | Will Stewart | Seetee Ship | Seetee | 1951 | 7/15/1951 | |||

| 16 | 18 | 16,27 | Isaac Asimov | Foundation | Foundation | 1951 | 9/15/1951 | |||

| 17 | 13 | 16 | Lewis Padgett | Tomorrow and Tomorrow and The Fairy Chessmen | Tomorrow | 1951 | 12/1/1951 | |||

| 18 | 16 | 17,21 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | Travelers of Space | Travelers | 1951 | 1/3/1952 | |||

| 19 | 23 | 18 | Robert E. Howard | The Sword of Conan | Sword | 1952 | 4/1/1952 | |||

| 20 | 24 | 19 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | Five Science Fiction Novels | King | 1952 | 4/1/1952 | |||

| 21 | 25 | 20,27,37 | Arthur C. Clarke | Sands of Mars | Sands | 1952 | 4/15/1952 | |||

| 22 | 19 | 20 | A. E. van Vogt | The Mixed Men | Mixed | 1952 | 5/1/1952 | |||

| 23 | 20 | 20 | Lewis Padgett | Robots Have No Tails | Robots | 1952 | 5/15/1952 | |||

| 24 | 21 | 20 | Clifford D. Simak | City | City | 1952 | 5/15/1952 | |||

| 25 | 27 | 21,32,39 | Isaac Asimov | Foundation and Empire | Empire | 1952 | 9/15/1952 | |||

| 26 | 26 | 21 | Leigh Brackett | The Starmen | Starmen | 1952 | 11/15/1952 | |||

| 27 | 22 | 21 | C. L. Moore | Judgment Night | Judgment | 1952 | 12/15/1952 | |||

| 28 | 34 | 21 | Robert E. Howard | King Conan | King | 1953 | 3/2/1953 | |||

| 29 | 35 | 22 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | The Robot and the Man | Robot | 1953 | 3/15/1953 | |||

| 30 | 36 | 23 | Hal Clement | Iceworld | Iceworld | 1953 | 4/15/1953 | |||

| 31 | 37 | 23 | Arthur C. Clarke | Against the Fall of Night | Against | 1953 | 4/15/1953 | |||

| 32 | 28 | 23 | Wilmar H. Shiras | Children of the Atom | Children | 1953 | 5/15/1953 | |||

| 33 | 38 | 23 | Isaac Asimov | Second Foundation | Second | 1953 | 5/15/1953 | |||

| 34 | 30 | 24 | Lewis Padgett | Mutant | Mutant | 1953 | 10/20/1953 | |||

| 35 | 32 | 25 | Jeffrey Logan (ed) | The Complete Book of Outer Space | Complete | 1953 | 10/20/1953 | |||

| 36 | 33 | 24 | Robert E. Howard | The Coming of Conan | Coming | 1953 | 10/25/1953 | |||

| 37 | 29 | 24 | Nat Schachner | Space Lawyer | Lawyer | 1953 | 11/1/1953 | |||

| 38 | 31 | 24 | C. L. Moore | Shambleau and Others | Shambleau | 1953 | 11/1/1953 | |||

| 39 | 45 | 26 | Arthur C. Clarke | Prelude to Space | Prelude | 1954 | 3/10/1954 | |||

| 40 | 44 | 27 | L. Sprague de Camp | Lost Continents | Lost | 1954 | 3/25/1954 | |||

| 41 | 41 | 26 | William Morrison | Mel Oliver and Space Rover on Mars | Mel | 1954 | 7/15/1954 | |||

| 42 | 43 | 26,27 | Murray Leinster | The Forgotten Planet | Forgotten | 1954 | 7/21/1954 | |||

| 43 | 42 | 28 | C. L. Moore | Northwest of Earth | Northwest | 1954 | 10/25/1954 | |||

| 44 | 39 | 28 | Robert E. Howard | Conan the Barbarian | Barbarian | 1954 | 11/1/1954 | |||

| 45 | 40 | 26 | Frederik Pohl & Jack Williamson | Undersea Quest | Quest | 1954 | 11/25/1954 | |||

| 46 | 51 | 28 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | All About the Future | All | 1955 | 1/15/1955 | |||

| 47 | 53 | 29 | Groff Conklin (ed) | Science Fiction Terror Tales | Science | 1955 | 2/15/1955 | |||

| 48 | 46 | 29 | Jack Williamson & James Gunn | Star Bridge | Star | 1955 | 3/25/1955 | |||

| 49 | 47 | 29 | F. L. Wallace | Address: Centauri | Address | 1955 | 4/25/1955 | |||

| 50 | 48 | 29 | Andrew North | Sargasso of Space | Sargasso | 1955 | 5/25/1955 | |||

| 51 | 52 | 29 | H. Chandler Elliott | Reprieve from Paradise | Reprieve | 1955 | 7/25/1955 | |||

| 52 | 50 | 30 | James Gunn | This Fortress World | Fortress | 1955 | 10/25/1955 | |||

| 53 | 49 | 29 | Robert Howard & L. Sprague de Camp | Tales of Conan | Tales | 1955 | 12/5/1955 | |||

| 54 | 56 | 31 | Andrew North | Plague Ship | Plague | 1956 | 2/5/1956 | |||

| 55 | 58 | 31 | Arthur K. Barnes | Interplanetary Hunter | Interplanetary | 1956 | 3/15/1956 | |||

| 56 | 57 | 31 | Judith Merril (ed) | SF: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy | SF: 56 | 1956 | NA | |||

| 57 | 54 | 31 | George O. Smith | Highways in Hiding | Highways | 1956 | 7/15/1956 | |||

| 58 | 55 | 31 | Frederik Pohl & Jack Williamson | Undersea Fleet | Fleet | 1956 | 9/1/1956 | |||

| 59 | 64 | 33 | Martin Greenberg (ed) | Coming Attractions | Attractions | 1957 | 3/15/1957 | |||

| 60 | 66 | 33 | James Blish | The Seedling Stars | Seedling | 1957 | 4/1/1957 | |||

| 61 | 62 | 33 | Murray Leinster | Colonial Survey | Colonial | 1957 | 4/15/1957 | |||

| 62 | 63 | 34 | Fritz Leiber | Two Sought Adventure | Two | 1957 | 5/15/1957 | |||

| 63 | 61 | 34 | Judith Merril (ed) | SF: ’57: The Year’s Greatest Science | SF: 57 | 1957 | 7/9/1957 | |||

| 64 | 67 | 34 | Poul Anderson & Gordon Dickson | Earthman’s Burden | Earthman’s | 1957 | 7/25/1957 | |||

| 65 | 60 | 34 | Bjorn Nyberg & L. Sprague de Camp | The Return of Conan | Return | 1957 | 8/25/1957 | |||

| 66 | 59 | 36 | Robert Randall | The Shrouded Planet | Shrouded | 1957 | 9/25/1957 | |||

| 67 | 65 | 34 | Mark Clifton & Frank Riley | They’d Rather Be Right | Rather | 1957 | 10/25/1957 | |||

| 68 | 74 | 36 | Tom Godwin | The Survivors | Survivors | 1958 | 2/25/1958 | |||

| 69 | 73 | 34,35 | Robert A. Heinlein | Methuselah’s Children | Methuselah’s | 1958 | 4/15/1958 | |||

| 70 | 70 | 34 | Frederik Pohl & Jack Williamson | Undersea City | Undersea | 1958 | 7/1/1958 | |||

| 71 | 72 | 36 | Judith Merril (ed) | SF: ’58: The Year’s Greatest | SF: 58 | 1958 | 7/15/1958 | |||

| 72 | 71 | 36 | Talbot Mundy | Tros of Samothrace | Tros | 1958 | NA | |||

| 73 | 69 | 36 | Robert Silverberg | Starman’s Quest | Starman’s | 1958 | NA | |||

| 75 | 68 | 48 | George O. Smith | The Path of Unreason | Path | 1958 | 7/25/1958 | |||

| 74 | 77 | 36 | Talbot Mundy | Purple Pirate | Purple | 1959 | NA | |||

| 76 | 78 | 38 | Judith Merril (ed) | SF: ’59: The Year’s Greatest | SF: 59 | 1959 | 6/30/1959 | |||

| 77 | 76 | 38 | Robert Randall | The Dawning Light | Dawning | 1959 | 8/25/1959 | |||

| 78 | 75 | 38 | Wallace West | The Bird of Time | Bird | 1959 | 10/25/1959 | |||

| 79 | 80 | 38 | Robert A. Heinlein | The Menace from Earth | Menace | 1959 | 11/25/1959 | |||

| 80 | 79 | 38 | Robert A. Heinlein | The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag | Unpleasant | 1959 | 12/25/1959 | |||

| 81 | 82 | 38 | James A. Schmitz | Agent of Vega | Agent | 1960 | 3/25/1960 | |||

| 82 | 81 | 38 | Edward E. Smith | The Vortex Blaster | Vortex | 1960 | 6/25/1960 | |||

| 83 | 83 | 39 | Frederick Pohl | Drunkard’s Walk | Drunken | 1960 | ||||

| 84 | 84 | 39 | John W. Campbell | Invaders from the Infinite | Invaders | 1961 | 3/15/1961 | |||

| 85 | 85 | 40 | Edward E. Smith | Gray Lensman | Gray | 1961 | ||||

| 86 | 86 | 41 | Everett B. Cole | The Philosophical Corps | Philosophical | 1962 | 12/10/1962 | |||

The first Gnome Press title would of course not have a list on the back panel. Lists take years to build.

Title(s) on: The Carnelian Cube

Titles displayed: none

Title(s) on back flap: 2

Missing: none

The back panel (1) of the first Gnome book, L. Sprague de Camp & Fletcher Pratt’s The Carnelian Cube, used the space for “Meet the Authors” biographies. Full four-color printing is expensive; someone – presumably jacket designer Kyle – decided to go with only two colors, which worked acceptably on the front panel but made the back panel barely readable. Although I’ve centered the text for this scan, the books themselves show a problem chronic to Gnome: the wrapping of the jacket was often off-center. The buyer would see the text moved much closer to the left edge and part of what should have been spine copy on the right.

The address is the only other piece of information, repeated from the back flap, which contained a tantalizing come-on: “Descriptive list of other current books sent on request.” This is foreshadowing. All future books would include some form of the Gnome mailing address on the back panel, another means for tracking the order in which the editions were released.

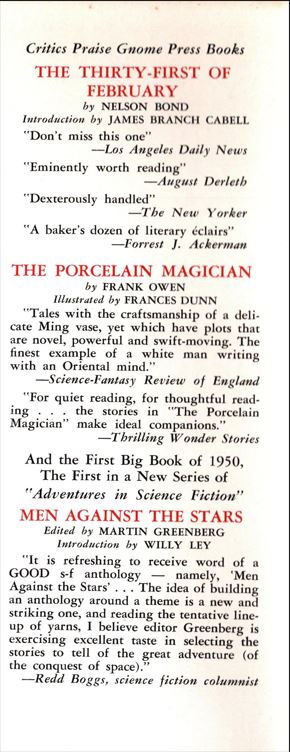

Title(s) on: The Porcelain Magician

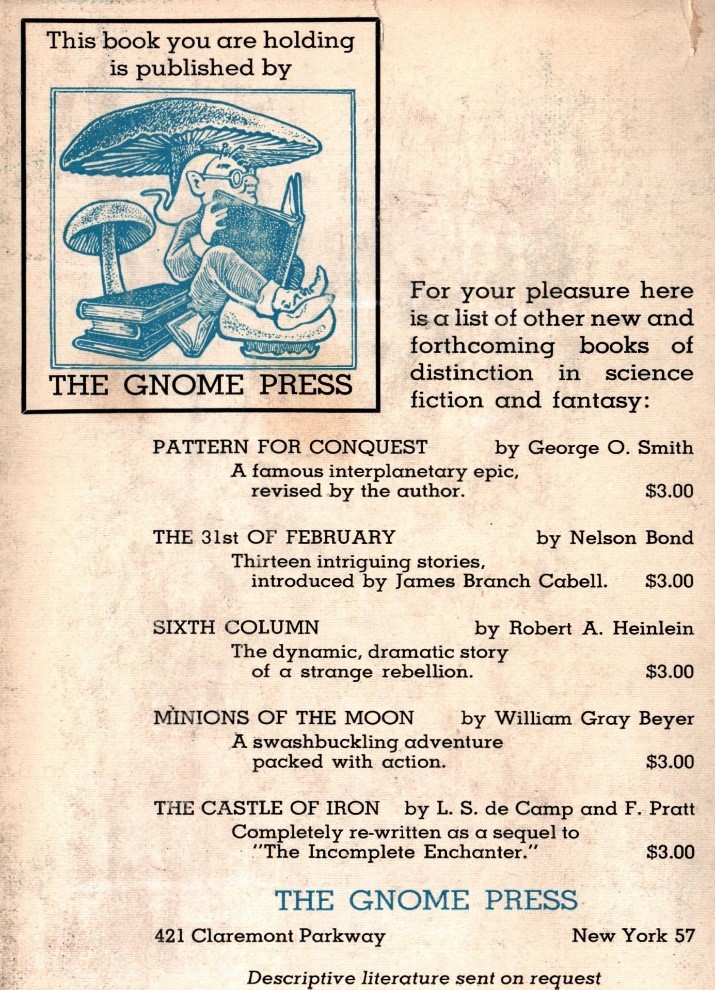

Forthcoming: 3, 4, 5, 7, 8

Title(s) on back flap: 1

Missing: none

One book sure to have been on that list of other current titles was Frank Owen’s The Porcelain Magician. The entirety of the back flap on Carnelian is devoted to it. By the time Owen’s book was released, Gnome could implicitly boast that it was a going concern with big and confirmed plans for the future, a claim somewhat belied by the decision to go down to a one-color cover. At least the use of black for the type made the text far more readable. Carnelian was relegated to the back flap and five forthcoming titles were displayed on the back panel (2). The panel also boasted the new Gnome logo: a bespectacled gnome reading a book, sheltered under a mushroom umbrella.

The list of forthcoming titles held an unanticipated flaw. Unlike Arkham’s miscalculation, all of these titles would eventually appear over the next eighteen months. The glitch was subtler. When released each book except one would sell for only $2.50 rather than $3.00. That’s far better news for buyers than a title that never appeared. Still, I wonder how many readers faithfully sent in their $3.00 in anticipation of the works, and whether they got refunds.

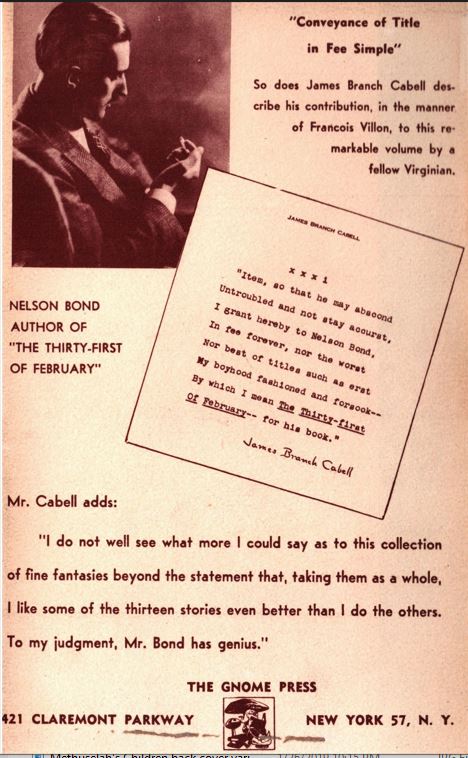

Title(s) on: The Thirty-first of February

Titles displayed: none

Title(s) on back flap: 1, 2

Missing: none

Nelson Bond was a major name in 1949; publishing one of his books was a coup. Naturally the back panel (3) was a hagiography of Bond. Gnome’s earlier titles were relegated to the back flap. The fact that the back flap mentions only Carnelian and Porcelain as “books now available to you” is powerful evidence that February is Gnome’s third release and not its fifth as the traditional listing has it. Succeeding back panels will only strengthen the evidence for a new dating, despite a few instances of uncertainty.

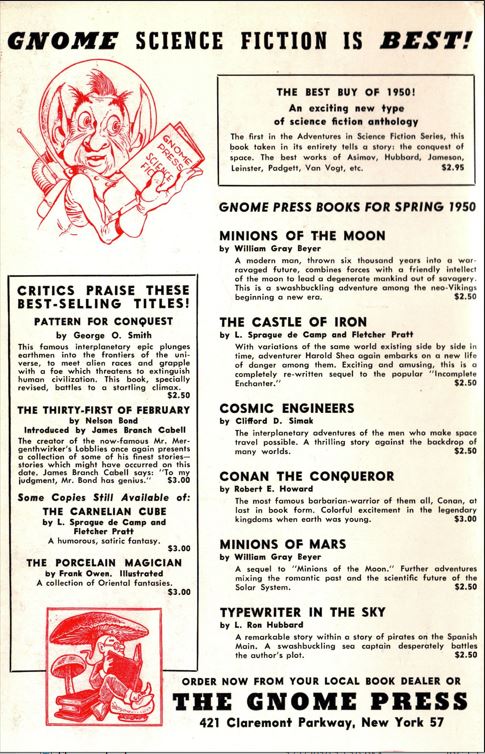

Title(s) on: Pattern of Conquest

Titles displayed: 1, 2, 3, 5

Forthcoming: [6], 7, 8, 9, 10, 14

Title(s) on back flap: 6

Missing: none

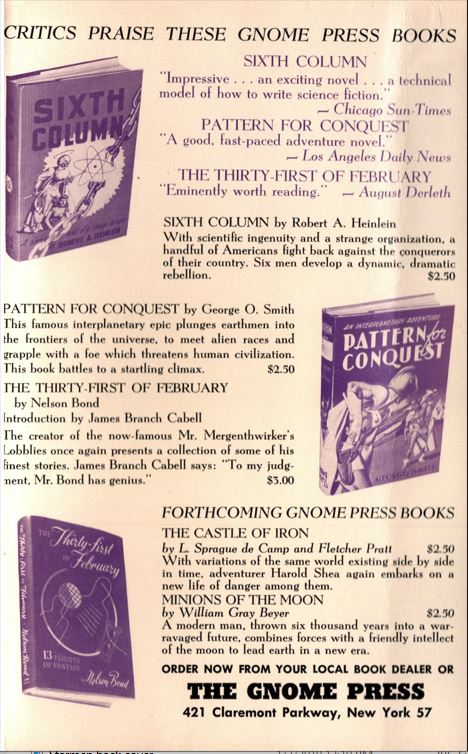

Title(s) on: Sixth Column

Titles displayed: 1, 2, 3, 4

Forthcoming: [6], 7, 8, 9, 10, 14

Title(s) on back flap: 6

Missing: none

George O. Smith’s Pattern for Conquest and Robert A. Heinlein’s Sixth Column must be discussed together. Their registrations were less than a month apart at the end of 1949. Their back panels (4,5) are identical except that Smith’s mentions Heinlein and Heinlein’s mentions Smith. It seems clear that the two books were meant to be publicly released at the same time or nearly so.

But it’s the rear cover that tells the best story of all, at least to historians looking back at Gnome. To emphasize that Gnome published science fiction, right under the banner headline GNOME SCIENCE FICTION IS BEST! a comically large-eared alien in a transparent bubble space helmet is pictured reading a book that is labeled GNOME PRESS SCIENCE FICTION on its rear cover. Aliens apparently read right to left, as in Hebrew or Japanese. The Elf under the toadstool official logo is smaller and at the bottom of the page. Half the titles on the page are still fantasy, though. From now through the end of Gnome’s run science fiction subsumed fantasy as the label for what the press published.

Gnome’s back covers were advertising for the press, not for the author. The box on the left side on Pattern’s back cover is example number one. “Some Copies Still Available of:” Carnelian and Porcelain. “Many,” “Lots,” or “Huge Piles” Still Available wouldn’t have given the image of a successful company that had to put forward. Even odder is the headline above, “CRITICS PRAISE THESE BEST-SELLING TITLES,” said titles including Column and Pattern. From today’s perspective, nothing is amiss about a critic praising these titles, but there is no record of any mention of them in 1949 when the dust wrappers were printed. Critics may have seen advance copies, but I have no evidence that they did.

The seven titles on the right-hand side of the page would become Gnome titles number 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14. I’m not playing a game with this: that’s really only six. There’s a story behind that. In fact multiple untold stories can be teased out of that list. This is the sort of hidden-in-plain-sight history that Ph.D. candidates only dream of for their dissertations.

Start from the top. The 1949 or 1950 buyer would see something very cool. “THE BEST BUY OF 1950! An exciting new type of science fiction anthology” Magazines were ephemeral. You bought them during the short window they appeared at a newsstand or, if you were lucky, obtained them from someone who had. Any story you missed was gone forever, unless it happened to appear in one of the cheaper mags that relied on reprints to bulk out their contents page. After seeing magazines get away with this, publishers slowly realized that an audience existed for reading major stories of the past that were unavailable to current readers.

The first anthology that fell within the genre of f&sf was The Other Worlds: 25 Modern Stories Of Mystery & Imagination, edited by Phil Stong and published by Garden City Publishing Co., Inc. in 1941. The contents reflected the mishmash that was f&sf in those days, a mixture of old fantasy and weird tales, modern horror, and that new-fangled scientifiction stuff. “Scientifiction” as a term is today associated with Gernsback and the 1920s, but it lasted a good long while and came to be the term that the general public used to describe the genre. Orwell used it in a 1940 essay and Stong’s introduction refers to it frequently. Only the small fan community used “science fiction” to refer to the field in the 1930s, but that was about to change.

Possibly the most influential, and certainly most active, insider’s insider was Donald A. Wollheim. As a fan he organized the first science fiction convention. He was part of Gernsback’s New York Science Fiction League, and then helped form the Futurians when schisming fans left the League. He started the Fantasy Amateur Press Association. He wrote sf beginning in 1934 and edited sf starting in 1940. And in 1943 he got Pocket Books, by far the leading paperback publisher in the country, to put out The Pocket Book of Science-Fiction, which may be the very first book title to include the words science fiction. Included are early proto-sf stories, but more importantly he ran stories almost hot off the presses from John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science-Fiction. (“Science-fiction” retained its vestigial hyphen then; Campbell’s removing it for the October 1943 issue marked a beginning of the modern era). Pocket never did another sf anthology in this era, so Wollheim moved to Avon and began cranking out Avon Fantasy Readers starting in 1947. The occasional indisputable science fiction story snuck in – heck, the first story in the first issue was Murray Leinster’s “The Power Planet” – but mostly the series was geared around names like A. Merritt, Robert E. Howard, and H. P. Lovecraft. The trend line was obvious, though, and Wollheim put out the Avon Science Fiction Reader starting in 1951 and followed that with two issues of an Avon SF and Fantasy Reader in 1953.

Greenberg must have had a more immediate concern. As a nexus in the small world of science fiction, he probably knew in advance that Wollheim would be editing a major anthology for the mainstream publisher Frederick Fell – a theme anthology with individual stories set on the nine planets, the Moon, the asteroid belt, and even the Sun. When released in 1950 it bore the title Flight Into Space: Great Science Fiction Stories of Interplanetary Travel. Having tiny Gnome be the first to publish a hardback theme anthology – something that author and editor Ellery Queen had already proved valuable in the mystery field – loomed like a golden trophy.

Men Against the Stars: An Anthology Arranged as a Future Story of the Conquest of Space would be Gnome title #6, the first of its books to appear in 1950. The race against Wollheim is the only reason I can think of for touting the forthcoming anthology on Pattern and Sixth without a title or editor’s name. Think about it. The point of listing these titles was to goad readers to order these titles, in advance if possible. How do you order such a book from your book dealer? Even if you brought in the cover all you could do was point to the description and ask the dealer to do the work of contacting Gnome to figure out what the heck it was.

The weirdest part of this mystery is that the title and editor appear on the back flaps of both books. Back flaps are on the same side of the dust jacket as the back panel. How could they have known the title for one but not the other? The implication is that the omission of the title and editor was deliberate. But that’s as implausible as any of the stories in the anthology.

Pattern and Sixth were announced far ahead of publication. A fanzine, Fanscient #9, cover dated Fall 1949, reports them as forthcoming on September 30 and October 15 respectively. That the title of the anthology was a last-minute choice is belied by the quoted review on both back flaps. The reviewer must have had the anthology by its final title before November 11, 1949, when Pattern was registered. I haven’t been able to trace where and when Redd Boggs’ review ran – “a leading newspaper of the science fiction world” means a fanzine and Boggs wrote prolifically for many – but the timing should have given Greenberg plenty of leeway to adjust his back panels.

Nevertheless, Greenberg’s propaganda worked. Ever since, historians of Gnome and sf in general point to Men Against the Stars as the first theme sf anthology. Greenberg himself doesn’t quite claim this, though. In his Foreward he calls it “a science fiction anthology which, taken in its entirety, tells a complete story.” Why the difference? Maybe because by 1950 he knew that the race was lost. Dell Books #305, published in 1949, was Invasion from Mars: Interplanetary Stories, selected by Orson Welles. Howard Koch’s radio script for “The War of the Worlds” leads off the volume, and the others are stories by big names – including Gnome authors like Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and Nelson Bond – from mostly minor and therefore harder to find magazines. It’s unquestionably a theme sf anthology and unquestionably earlier than Men Against the Stars and unquestionably would have been seen by an audience 100 times larger, especially with Welles’ name on the cover. You can’t control your destiny. Greenberg would run smack into this wall over and over in Gnome’s short history.

Another example of future propaganda appears in the list of six books that follows, under GNOME PRESS BOOKS FOR SPRING 1950. Did Greenberg honestly think he could publish seven books (those six plus the unnamed anthology) by Spring of the next year? More likely he knew he was stretching reality just as much as any of his authors. Readers, even if they had already been burned by the unreliable schedules and short lives of the small presses, were given many reasons to suspend their disbelief. The list had something for everyone: thrilling science fiction tales of an incredible future, the first appearance of Conan in book form, fantasy from name authors.

More was promised than possibly could be delivered, though. In fact, Greenberg published a total of six books in all of 1950. Minions of Mars never saw print in that year. Or ever. Why is a mystery I’ve never seen answered. William Gray Beyer has only six titles listed in the ISFDB and four of the six are multi-part Minions stories. Minions of the Moon appeared in the leading pulp magazine of the time, Argosy, in 1939. Minions of Mars and Minions of Mercury followed in 1940, Minions of Shadows in 1941. As with almost every title Gnome published in those years, all Greenberg had to do was secure the rights to already written and printed stories, set them up in type, and find a cover artist. He must have had the rights or else why list the book as a forthcoming title? Did Beyer balk for some reason? He is an utterly obscure author, and no more than a sentence of biography is available to me.

As I mentioned earlier, the five books that were published included Gnome Press volumes number 7, 8, 9, 10, and 14. Number 11 wasn’t mentioned at all. A quick peek at the back cover reveals that it wasn’t mentioned on Men. It wasn’t mentioned on Castle. It wasn’t mentioned on Minions. It wasn’t mentioned on Conqueror. It wasn’t mentioned on Cosmic. It was never mentioned at all by name by Gnome before it suddenly appeared in bookstores. The name of this volume not worthy of publicity? I, Robot.

This is another deep mystery. Asimov wasn’t the powerhouse he is today, but he was many levels above Beyer in the sf hierarchy. The robot stories were half of his claim to fame along with the Foundation stories. Since Gnome would publish the Foundation trilogy starting in 1951, Greenberg must have already had a relationship with him that he would want to protect. The one clue that may possibly have a bearing on this puzzler is the last story in the collection. “The Evitable Conflict” wasn’t even published for the first time until the June 1950 issue of Astounding. The story, of course, had been written and sent in months earlier, and Asimov bundled it up with his other robot stories and got it in to Gnome on June 8, 1950. Greenberg might have been reluctant to publicize a book whose full content wasn’t in his hands. Conversely, he may have been so excited to pull off this coup that he turned the entire book around in such a rush – it was apparently published on December 2 – that all of his other covers were already locked in stone and unchangeable in time. Either way, the omission tells us a good deal about the uncertainty and haphazard nature of the business in 1949.

One more untold story lies in the last title on the page, Typewriter in the Sky. At the time L. Ron Hubbard was another name levels above Beyer who was still publishing stories regularly through 1949 and into 1950. The two stories here – the other being “Fear” – were from 1940 so needing to wait upon publication couldn’t be an issue. 1950 notably saw Hubbard’s blockbuster “nonfiction” bestseller Dianetics and that may have thrown a wrench into Greenberg’s schedule. Did Hubbard not want both books to appear at the same time? At any rate, the Gnome book got bumped into the middle of 1951.

Gnome would continue to use almost every one of its back covers as advertisements for itself, to paraphrase Norman Mailer, but none of them are as deep with story and intrigue and archaeological significance as Pattern for Conquest. It’s a treasure chest as wonderful as any pirate’s and far more real.

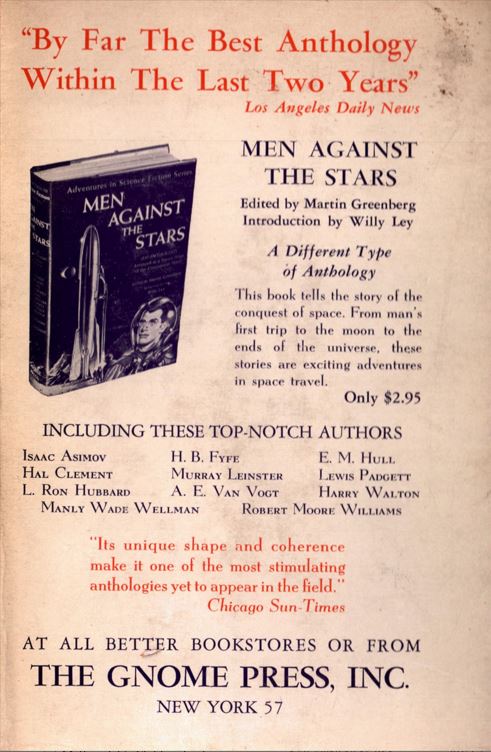

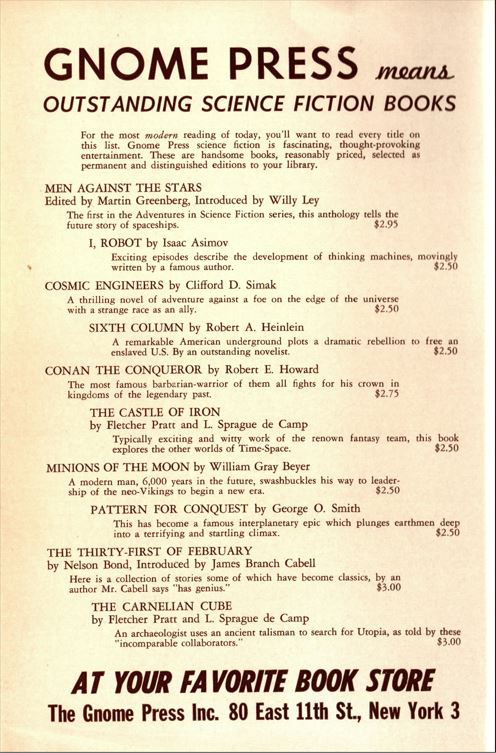

Title(s) on: Men Against the Stars

Titles displayed: 3, 4, 5

Forthcoming: 7, 8

Missing: 1, 2

When Men itself appeared, Greenberg was more cautious in his title selection on the back panel (6). Only the next two forthcoming titles were mentioned. Gnome’s first two titles were not mentioned. Amazingly, Porcelain would never be seen again. It’s difficult to devise an alternate explanation other than it’s having sold out, although that’s in stark contrast to the belief that the fantasies were poor sellers. The overly cutesy gnome and spaceman are gone as well. The fantasy gnome would return only once and in different form; the spaceman would appear temporarily in 1951 and 1954 and irregularly on jacket spines.

Greenberg had a hit on his hands – Men would become one of Gnome’s top sellers – and knew it. He devoted the entirety of the back panel (7) of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s The Castle of Iron to the anthology. Suddenly missing, though, is Gnome’s street address. Bookstores evidently were now beginning to regularly stock Gnome titles. Or was The Gnome Press, New York 57 sufficient information in those pre-zip code days?

More surprising is that again no mention of Gnome’s first two releases is made anywhere on the jacket. The only possible reason to omit de Camp and Pratt’s previous Gnome book is that it had sold out, or so readers must have assumed.

And that would explain why The Castle of Iron gets its due on Minion’s back panel (8).

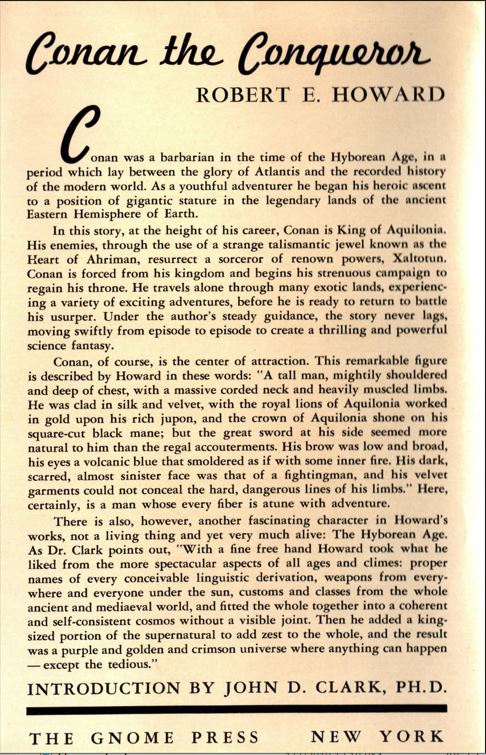

Title(s) on: Conan the Conqueror

Titles displayed: 9

Back Flap: 8, 10

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

The next title deserved to bask alone in its glory. The appearance of a Conan novel was a major event and Greenberg knew to present it as such. He solicited an Introduction from Conan expert John D. Clark, a literal rocket scientist and member of fandom since the 1930s. Kyle drew a two-page map of Hyborea for the endpapers. The back panel (9) was Conan all the way. Even the address was reduced to an elegant “The Gnome Press New York” as if it were a Roman inscription.

The back flap continues the austere look. All of Gnome’s early works are gone. Only Minions, the most recent release, and Clifford D. Simak’s Cosmic Engineers, the next release, are mentioned.

Title(s) on: Cosmic Engineers

Titles displayed: 6, 9

Back Flap: 7, 8

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

The lack of a full list was repeated on the next several books. Cosmic had the two hits, Men and Conqueror, on the back panel (10) with the two previous books on the back flap. The one surprise is a new address for Gnome. Greenberg moved the office from his house to an office on East 11th Street.

I, Robot has an almost identical back panel (11), merely swapping in the previous release for Greenberg’s anthology. The back flap returns the title listing, with five titles. Men is missing, another suggestion that Gnome’s books were selling out their runs.

Title(s) on: Journey to Infinity

Titles displayed: 1, 3, 4, 5,6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Missing: 2

Or were they? Greenberg’s sole book in the first quarter of 1951 was another of his Adventures in Science Fiction anthologies. Journey to Infinity. The book list returns to the back panel (12) and so do some of the missing titles. Men is back. Carnelian is back. Gnome has matured into a press with a history, a full line, and books that have been reprinted after having sold out.

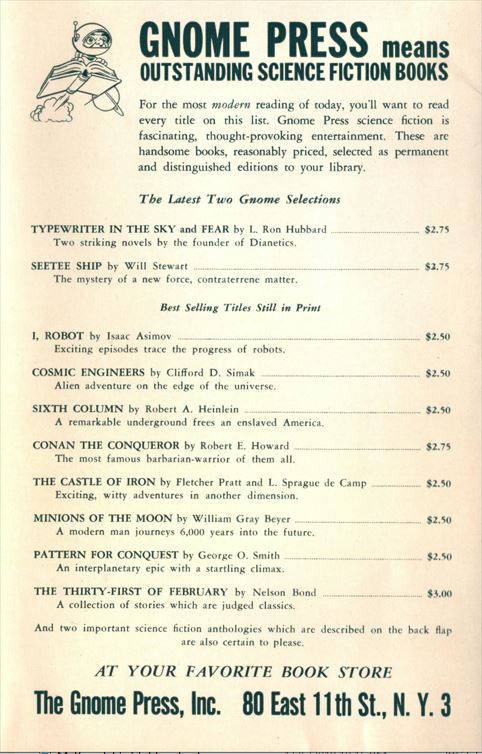

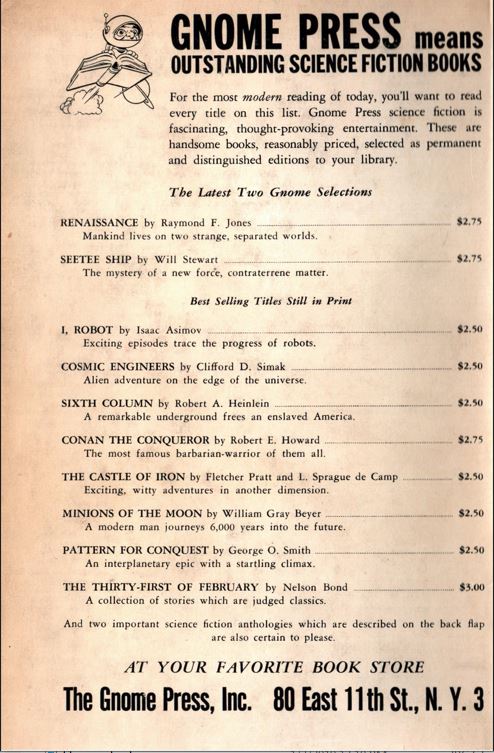

Title(s) on: Renaissance

Titles displayed: 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15

Back Flap: 6, 12

Missing: 1, 2

Raymond F. Jones’ Renaissance was registered in April of 1951, L. Ron Hubbard’s short novel omnibus Typewriter In the Sky/Fear in May, and Will Stewart’s Seetee Ship in July. Yet the evidence on the back panels indicates that the three were designed to appear as a block.

Title(s) on: Typewriter in the Sky/Fear

Titles displayed: 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15

Back Flap: 6, 12

Missing: 1, 2

Title(s) on: Seetee Ship

Titles displayed: 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15

Back Flap: 6, 14

Missing: 1, 2, 12

In a round robin of naming, the back panel (13) on Renaissance, the first registered, lists “The Latest Two Gnome Selections” as Typewriter and Seetee, which would not be registered for months. Typewriter’s back panel (14) give the latest two as Renaissance and Seetee. Seetee’s back panel (15) breaks the pattern of labeling titles as the “latest,” but lists Renaissance on the back panel and Typewriter on the back flap.

Whatever Greenberg intended, the books appeared in the order registered, from the evidence of their separate appearances in Kirkus Reviews. Renaissance came first, in the March 15 issue, Typewriter in the April 15 issue, and Seetee not until the June 15 issue. Similarly, Renaissance’s first newspaper review appeared on May 3, while the other two books had to wait until July 15. Seetee Ship must have been especially delayed, because a squib in the fanzine Fantasy Times #122, January 1951, said that the book “has been postponed again, this time until May.”

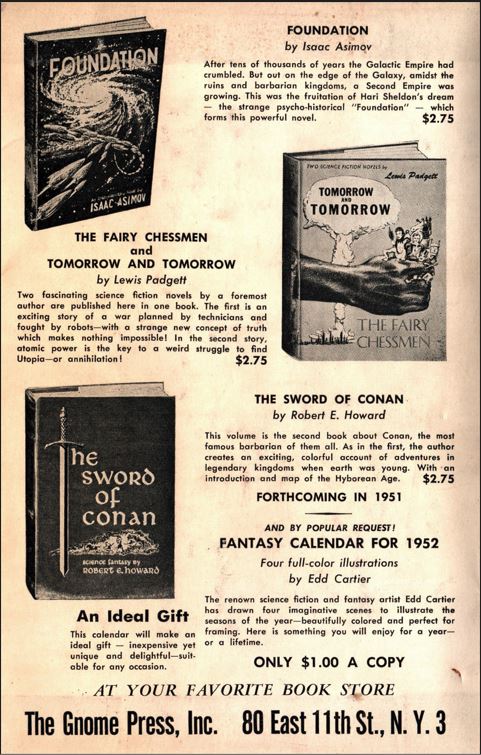

Titles displayed: 16, 17

Forthcoming: 19

Back Flap: 12, 14

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15

The back panel (16) on the next two releases was identical, the first time Gnome made a single image do. Again a near-simultaneous released is implied, although no evidence exists that the books weren’t released two months apart as the registration indicates. Isaac Asimov’s Foundation and Lewis Padgett’s pair of novellas Tomorrow and Tomorrow and The Fairy Chessmen advertise each other without any mention of previously published titles. (Greenberg had an odd habit of using variant titling or naming for the back panel. Tomorrow is consistently given as The Fairy Chessmen and Tomorrow and Tomorrow although all evidence, including the copyright registration, is that the order is the reverse. I will give what seems to be the proper bibliographic nomenclature and point out where it is violated.)

The actual next Gnome release would be Greenberg’s third anthology, Travelers of Space. No mention of it is made either. The anthologies were not just big sellers but Greenberg’s pet project, gifted with larger sizes and much nicer boards than the rest of the titles. Unless he held them in obeyance to slot in when there would otherwise be too long a lag between releases, it’s hard to understand why he wouldn’t have featured it on a back panel that was half given over to forthcoming projects. And that explanation can’t apply to Travelers. Science Fiction Newsletter #21, July 1951, reported that an unnamed anthology – Travelers from the description – would be the lead title on Gnome’s autumn list, so presumably between Foundation and Tomorrow. So would The Sword of Conan, scheduled for October, according to that same issue. Greenberg just could not get his books out on schedule. That’s apparently why Sword, the second Conan book, got the prime forthcoming slot. Some publishing snafu pushed it back to April 1951, a long stretch away from Foundation’s September 1950 release.

Gnome had produced fantasy calendars with art by Hannes Bok, Edd Cartier, and Frank R. Paul for 1949 and 1950. Sources disagree whether a 1951 calendar exists. The Fantasy Calendar for 1952 is labeled “By Popular Request!” meaningful only if fans wrote in after not seeing a calendar the year before. That’s also the way the news was publicized in the fan world. The fanzine Science Fiction Newsscope #13, September 1951, said that “Gnome is reviving its famed FANTASY CALENDAR this year.” A revival can only occur after an absence. And yet a one-leaf calendar with no mention of Gnome was sold by Currey with provenance given by Donald A. Wollheim. You’ll see it in The Fantasy Calendars and can decide for yourself.

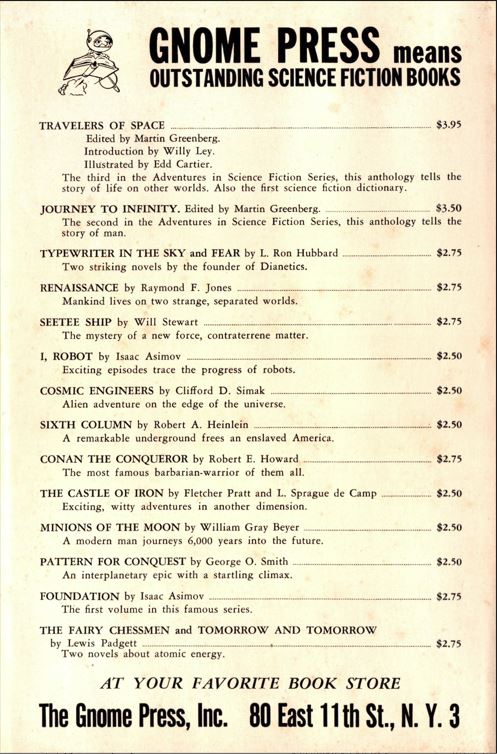

Title(s) on: Travelers in Space

Titles displayed: 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 6, 13, 14, 15

When Travelers finally appeared in January 1952, Journey to Infinity leads the list on the back panel (17), with explicit mention of its being second in the Adventures series. This should not be surprising since Travelers is the third in Greenberg’s Adventures in Science Fiction Series, except that the traditional order has Travelers appearing first, an impossibility. Men, the first in the series, is still missing but not for long. A sad-eyed gnome, his back broken by a staggering load of a dozen fat books, makes its first appearance. After the heavy cross-promotion of Renaissance, Typewriter, and Seetee, their omission here is another puzzling marketing decision.

Title(s) on: The Sword of Conan

Titles displayed: 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 6

But they’re back on Robert E. Howard’s The Sword of Conan. The descriptions on the back panel (18) are shortened so that fourteen titles can be put into the space that only had ten.

Title(s) on: Five Science Fiction Novels; Men Against the Stars variant

Titles displayed: 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16,17, 18, 19

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 6

The back panel (19) on Five Science Fiction Novels, a Greenberg anthology not part of his Adventures series, at first glance looks identical to that of The Sword of Conan. A careful count reveals that the Conan title is slipped into the list next to the earlier Conqueror. As with all of his anthologies, Greenberg added an extra quarter-inch to his standard page height, making his books stand out from the rest. The additional height allowed him to add a title without the list appearing squashed.

This back panel also appears on the variant dust jacket for Men Against the Stars. CHALKER calls this a “reprint” while ESHBACH and KEMP call it a “second printing.” I’m not sure what the distinction is between these.

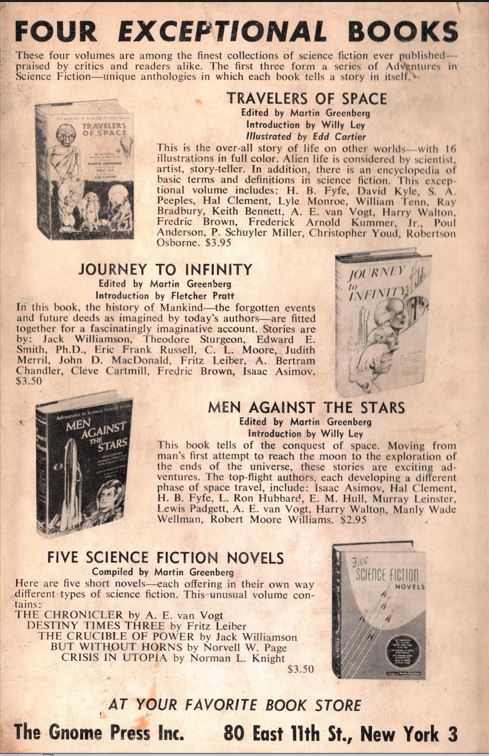

Title(s) on: Sands of Mars; The Mixed Men; Robots Have No Tails; City

Titles displayed: 6, 12, 18, 20

Back flap: 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24

Missing: 2, 3

Having Men back in print clearly thrilled him. The next four Gnome books were registered over a month’s span and not one of them was mentioned on their back panels (20), passed over so that Greenberg could proudly display his four anthologies.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Sands of Mars, A. E. van Vogt’s The Mixed Men, Lewis Padgett’s Robots Have No Tails and Clifford D. Simak’s City must be thought of parts of a simultaneous release, even more so than Renaissance, Typewriter, and Seetee. Robots and City are virtual twins. They were copyright on the same day, reviewed their first reviews in the same month, and were mentioned in newspapers only two days apart. Robots gets placed ahead only because its Kirkus mention is earlier.

The other titles have temporarily been moved to the back flap, where, without descriptions, the page is filled with a full eighteen titles in no discernable order, although books by the same author are paired. Only Porcelain and February remain among the missing; they will never return. Carnelian suddenly reappears after being absent for a year. Was its second printing delayed this long? This is wildly improbable. The text is identical to the first, printed at Kyle’s Advisor Press, which he had stopped using in the 1940s. Why would he have gone back and printed more copies on those creaky presses when he was dealing with more modern outfits regularly? Only the ISFDB – a somewhat creaky source itself – gives an actual date – 1949 – for the reprinting, which is reasonable but totally unsourced.

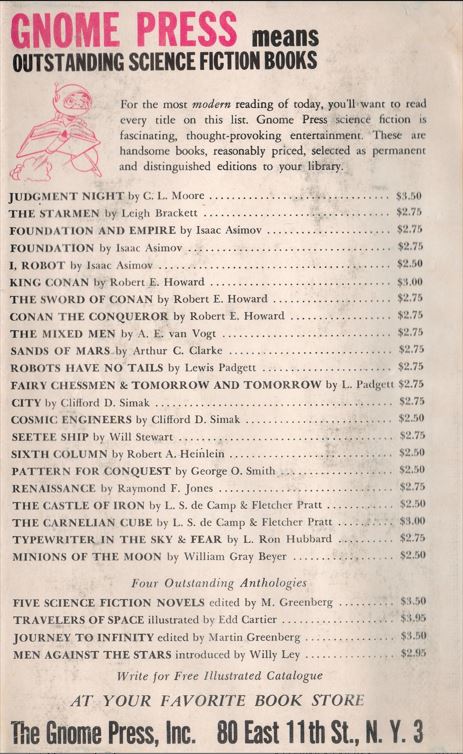

Title(s) on: Foundation and Empire; The Starmen; Judgment Night; King Conan

Titles displayed: 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28

Missing: 2, 3

Another quartet of books, another set where the same back panel (21) is used. Isaac Asimov’s Foundation and Empire, Leigh Brackett’s The Starmen, C. L. Moore’s Judgment Night, and Robert E. Howard’s King Conan were released over a four-month period, though, a long time to have titles on the cover with no way to buy them. You’d think Greenberg would be counting on advance orders to help his always-in-peril cash flow.

Title(s) on: The Robot and the Man; Journey to Infinity variant; Travelers of Space variant

Titles displayed: 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

Missing: 2, 3, 15

Greenberg celebrated his fifth anthology The Robot and the Man, the fourth in the Adventures in Science Fiction series, by releasing new printings of Journey and Travelers and using the same back panel (22) for all. This reliably dates the reprints to around March 1953. The five anthologies top the listing. Other titles are grouped by authors: three by Howard, four by Asimov, two by Clarke; two by Padgett; two by Simak; two by de Camp. Clement, Shiras, Brackett, van Vogt, Heinlein, Hubbard, Beyer, Smith and Jones round out the list. This is a stunning collection of the cream of the 1940s authors, compiled despite the founding of a dozen other small presses and a few mainstream houses competing for the same small group. At the beginning of its fifth year of existence, Gnome had what we can now look back and see as a pantheon of 1940s science fiction plus important titles of fantasy. To be honest, nothing Gnome published later rivals these in importance. Greenberg had the good fortune to be there at the beginning, with cream begging to be skimmed off the top. That he gathered the biggest and best share is impressive.

The list contains four books that hadn’t been published yet but soon would be, making six registrations in two months, a possible glut on the market. If so, Greenberg eased back with a five-month break. Seetee is missing, never to be seen again. The early works are selling out.

Title(s) on: Iceworld; Against the Fall of Night; Children of the Atom; Second Foundation

Titles displayed: 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15

Those four books were Hal Clement’s Iceworld, Arthur C. Clarke’s Against the Fall of Night, Wilmar H. Shiras’ Children of the Atom, and Lewis Padgett’s Mutant. Unsurprisingly, they all shared a common back panel (23).

This back panel splits Clement’s title into two words, Ice World. It’s written as one word elsewhere on the dust jacket, on the spine of the boards, and inside the text pages. Just another Gnome oddity. Another five titles disappear from this back panel, never to be seen again.

Title(s) on: Mutant; The Coming of Conan; Space Lawyer; Shambleau and Others

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 37, 38

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15

After the five-month gap, Gnome again released four of its titles within a month and again provided one back panel (24) for the four to share. Two major titles, Sixth and I, Robot, leave with this back panel. Why Greenberg didn’t reprint these guaranteed sellers is a mystery. Asimov certainly complained about the lack of royalties and so may have blocked a new printing. Heinlein enjoyed a better relationship, though, and would enter into talks with Gnome about a reprint in the late 1950s. But that book also had a cheaper edition – a Signet paperback renamed The Day After Tomorrow – and that may have taken precedence.

Title(s) on: The Complete Book of Outer Space

Titles displayed: none

Back flap: 6, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15

Not mentioned on that back panel was a book probably released in exactly the same time frame as the four new books. This was the oddest – and perhaps shrewdest – move Greenberg ever made. He reprinted a magazine called The Complete Book of Outer Space in hardcover, making only the minimal number of adaptations to turn it into a Gnome book. The hardcovers were crucial, allowing him to sell the book to libraries who were at the time averse to soft-covered books. The magazine’s original rear cover was used for the back panel (25), but a listing of Gnome books could be found on the back flap. The increased number of missing books has a specific cause: all the remaining fantasy titles were omitted from this very hard-science nonfiction book.

Complete was registered by Maco Magazine Corp. on October 20, 1953, the same date as Mutant. Greenberg acquired his copies from Maco but there is nothing to indicate whether he received the copies at the same time the magazine was published or later. The first newspaper mention is not until January 3, 1954, a somewhat longer than usual lag that might indicate a later Gnome release. Mutant made it into a library by November 21, 1953. Unfortunately, C. L. Moore’s Shambleau, registered on November 1, 1953, also took until January to hit a newspaper, making that line of reasoning moot. Without a reason to think otherwise, I am lumping the four Gnome books with identical back panels together and setting Complete after them as either the last book in 1953 or the first one in 1954.

Title(s) on: Prelude to Space; Mel Oliver and Space Rover on Mars; The Forgotten Planet variant, Undersea Quest

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 10, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 45

Back flap: 25, 33

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 43, 44

In 1954, Gnome slapped the same set of back panels (26) on yet another quartet of books, Arthur C. Clarke’s Prelude to Space, William Morrison’s Mel Oliver and Space Rover on Mars, Murray Leinster’s The Forgotten Planet, and Frederick Pohl and Jack Williamson’s Undersea Quest. These titles, however, overlap the registration dates of other titles.

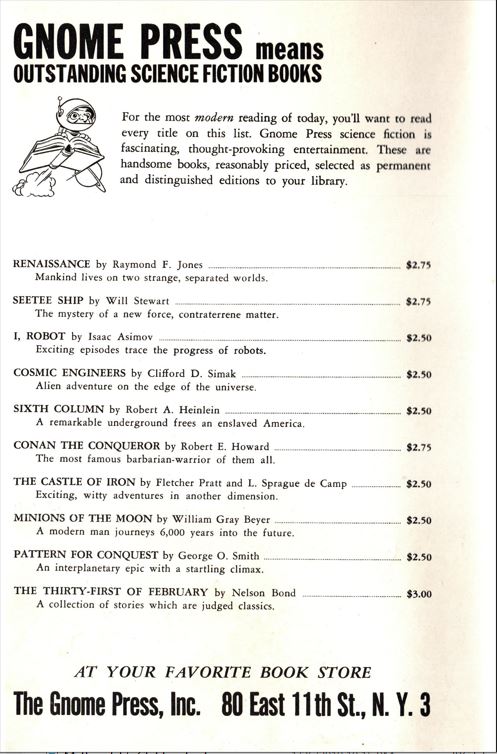

Title(s) on: Lost Continents; The Forgotten Planet; Foundation variant; Sands of Mars variant

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 10, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 45

Back flap: 25, 33

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 43, 44

Those include L. Sprague de Camp’s Lost Continents and Murray Leinster’s The Forgotten Planet, along with new printings of Foundation and Sands. The title listing on the back panel (27) is identical; omitted are the spaceman gnome logo and the line “Write for Free Illustrated Catalogue.” The two nonfiction selections Complete and Continents get their own section. Presumably for the power of their names, Complete is not credited to the unknown editor, Jeffrey Logan, but to the famous names whose articles were reprinted. Well, sort of famous. If he were truly famous, wouldn’t someone have noticed that Willy Ley’s name was typed as Willey? The mistake was repeated on the next panel as well.

How can I say that Forgotten Planet overlapped with Forgotten Planet? Two different covers were prepared: one features a man facing off against a giant beetle signed by Emsh, the other star map signed by Binkley. The Binkley cover was the general release with five differently colored boards; the Emsh cover was quickly removed from circulation if it ever got there, therefore I’m relegating it to variant status. See the title for the details.

Foundation and Sands belong to the group of true second printings unacknowledged by Gnome. Why they weren’t is another mystery. Most publishers of the day crowed about multiple printings and used them as psychological bait in their advertising. You, the potential buyer, you should – must – buy this book because you’ll be missing out on both a good book and being part of the in crowd. The prestige for both Gnome and the authors of having a printing sell out should have been a similar trigger.

CHALKER puts the Foundation reprint squarely in 1954 but gives Sands a date of 1955. That seems highly unlikely to me: by 1955 Gnome had switched to different back panels. Finding a beetle cover on a 1955 printing would also require some contorted explaining.

Title(s) on: Northwest of Earth; Conan the Barbarian; All About the Future

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 22, 23, 30

The new set of back panels (28) begin appearing in late 1954, and are found on C. L. Moore’s Northwest of Earth, Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, and Greenberg’s sixth anthology, All About the Future.

The notable change on this panel is the bumping up of the “Five Outstanding Anthologies” to Six Outstanding Anthologies” – in bold, yet – to celebrate Greenberg’s new compilation. The fiction list is brought up-to-date and loses some older titles: Mixed permanently and Tomorrow, Robots, and Iceworld temporarily

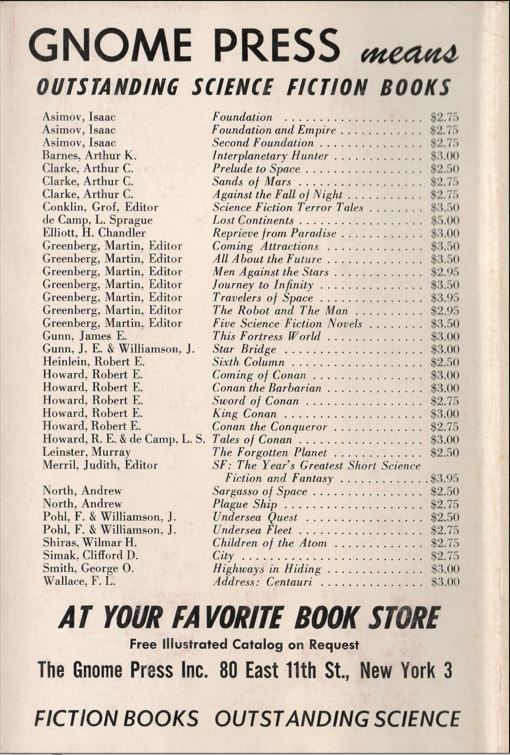

Title(s) on: Science Fiction Terror Tales; Star Bridge; Address: Centauri; Sargasso of Space; Reprieve from Paradise; Tales of Conan

Titles displayed: 5, 6, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30,31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 ,44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 22

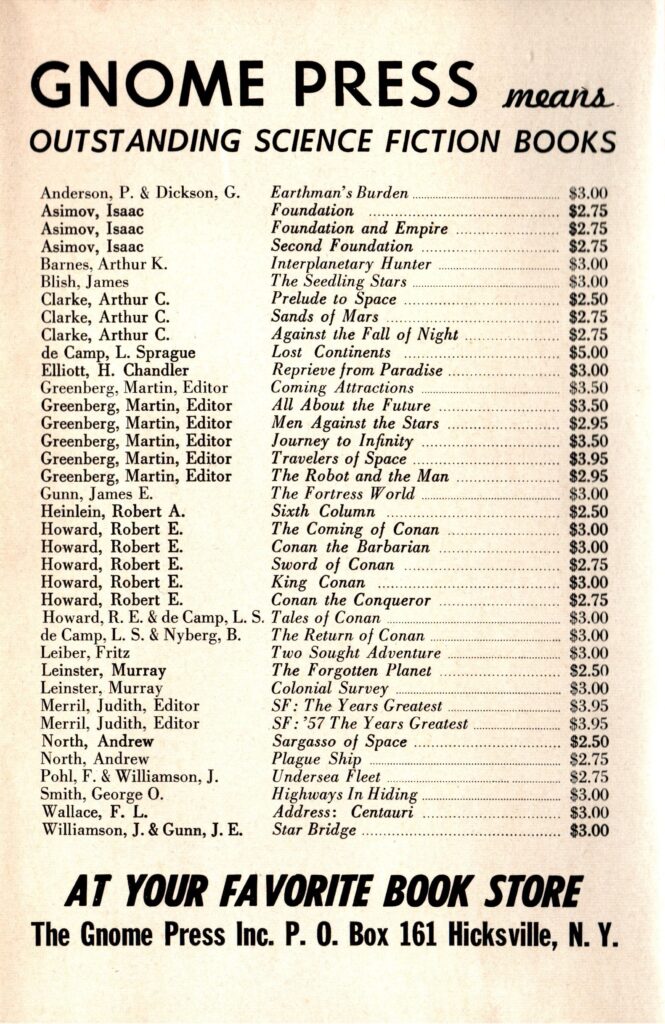

1955 brought a startling new look to the back panel (29). All books are listed alphabetically by author. An author’s books had been grouped together in the past but the clumps were randomly distributed. Switching the focus from the title to the author is as much a major psychological move as listing second printings would have been. Magazine science fiction editors had long known that favorite authors drove sales and featured their names in large-sized type on covers. Paperback editors numbered their books and listed titles in numerical order, implying that their wares were interchangeable: order blanks on back pages normally asked for number rather than title and author. Gnome’s lack of any overall method stood out as an oddity; one corrected when Greenberg would stick to this style for the next three years.

New titles added were Groff Conklin’s anthology Science Fiction Terror Tales, Jack Williamson and James Gunn’s Star Bridge; F. L. Wallace’s Address: Centauri, Andrew North’s Sargasso of Space, and H. Chandler Elliott’s Reprieve from Paradise. Not added was the last title released in 1955, Tales of Conan by Robert Howard with L. Sprague de Camp finishing and revising the stories, even though that book too bore this back panel. That appears to be an accident or afterthought. James Gunn’s This Fortress World has a much revised back panel (30) that lists Tales but is registered six weeks earlier and almost certainly was released first.

Title(s) on: This Fortress World

Titles displayed: 5, 6, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 58, 59

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 22

This back panel is the epitome of Gnome, listing 43 titles, more than ever before or after. Fortress made the listing, and Tales has finally been added along with Pohl & Williamson’s Undersea Fleet and Greenberg’s seventh and last anthology, the nonfiction compilation Coming Attractions. Those two can’t possibly belong there: Fleet was the last book issued in 1956, while Attractions didn’t appear until March of 1957, a full seventeen months after Fortress. Not surprisingly, neither bore this back panel nor did Tales.

The back panel of Fortress is transition in another way. Up until now, the book listings had their share of oddities but mostly made chronological sense. After Fortress all hell breaks loose. Gnome time moves into an alternate universe where the world gets stuck in a perpetual present.

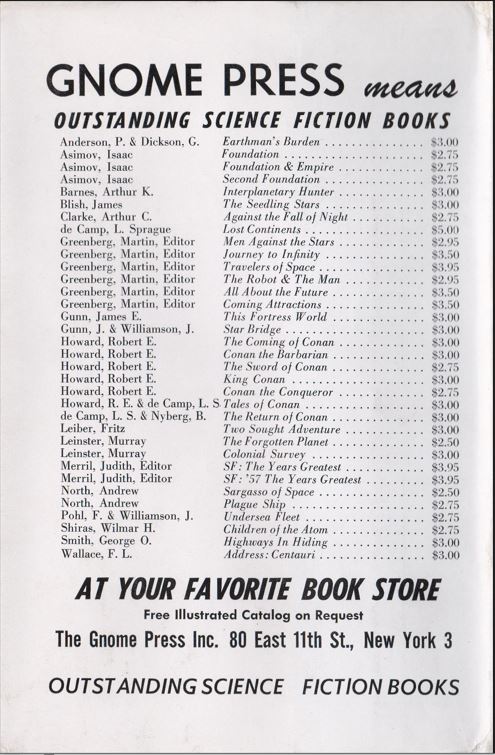

Title(s) on: Plague Ship; Interplanetary Hunter; SF: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy; Highways in Hiding; Undersea Fleet

Titles displayed: 5, 6, 9, 12, 16, 18,19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 22, 26, 27, 30, 34, 36, 37, 38, 41, 43

All five 1956 titles shared a single back panel (31). They were Andrew North’s Plague Ship, Arthur K. Barnes’ Interplanetary Hunter, Judith Merril’s anthology SF: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy, George O. Smith’s Highways in Hiding, and finally Frederik Pohl & Jack Williamson’s Undersea Fleet. All four titles are included in the listing. This is the only back panel to include all seven of Greenberg’s anthologies and all seven of the Conan books. Proofing was the not the strong suit of whatever assistant Greenberg had at the time. Groff Conklin’s name is spelled with one “f” and Robert A. Heinlein’s middle initial now appears as “E,” probably a carryover from all those Howard, Robert E.’s just below it. Merril’s anthology is listed as SF: The Year’s Greatest Short Science Fiction and Fantasy, a qualifier not seen anywhere else except for back panel 32, which copied this book list.

The list covered all books through the beginning of 1957, meaning that a year’s worth of forthcoming books was included on Plague, registered on February 5, 1956. To make room for them, ten titles were jettisoned, never to be seen again: Tomorrow, The Starmen, Judgment, Iceworld, Mutant, Coming, Lawyer, Shambleau, Mel, and Northwest.

Title(s) on: Foundation and Empire variant

Titles displayed: 5, 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 22, 26, 27, 30, 34, 35, 37, 38, 41, 43

Back panel 32 is not a new display. It clearly was intended to duplicate back panel 31 and did except for a bizarre addition of unneeded type. Foundation and Empire joined Foundation in getting a true second printing, although Greenberg cheaped out by cutting the cover from four-colors to a blue overlay. CHALKER again assigns this to 1955 and again I have to disagree. The back panel (32) places it no earlier than 1956 and probably very early 1957 since all 1956 issues are mentioned. CURREY mentions a second state dust jacket with 32 titles but this isn’t it: there are 36 titles listed. The 32-title variant is shown here as back panel 39, from around 1960; this one is mentioned nowhere that I know of.

Greenberg had run the banner “GNOME PRESS means/outstanding science fiction books” on two lines across the top of the back panel since Journey in 1951. The type font changed occasionally but it was a near constant that regular purchasers would automatically note and pay little attention to. Perhaps that’s how this wild error slipped by. Someone, somewhere in the process, duplicated the second line at the bottom of the panel. Or tried to duplicate. Somehow the blocks of type were reversed, so that the line reads “fiction books outstanding science” in a different font with an inexplicable space in “outst anding.” Only Gnome.

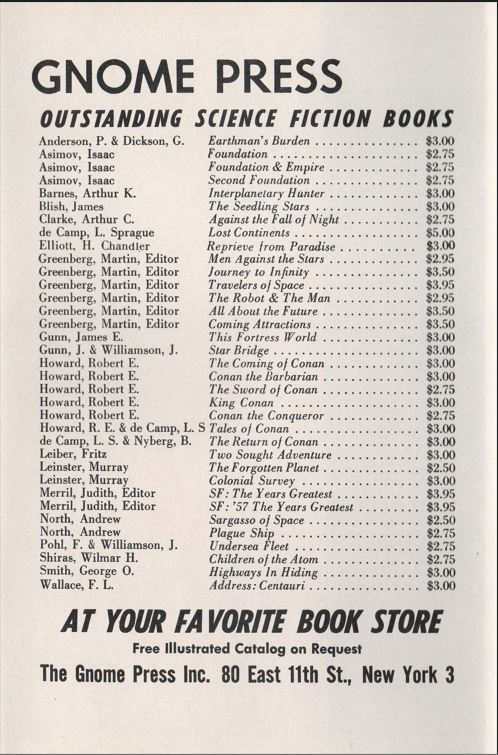

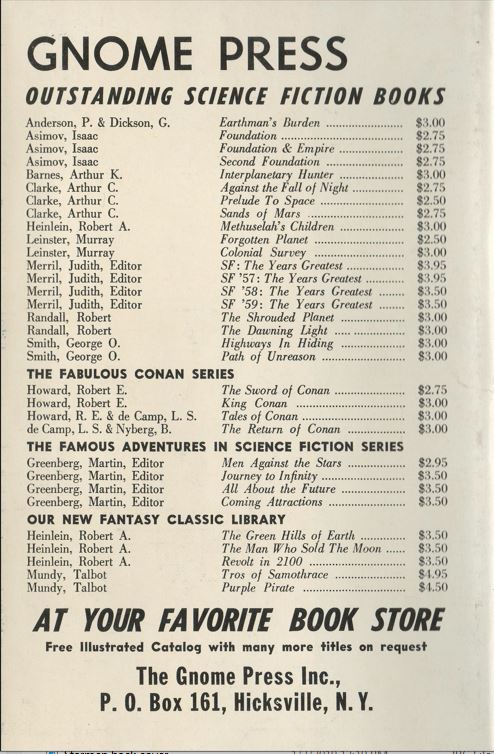

Title(s) on: Coming Attractions; The Seedling Stars; Colonial Survey

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 36, 40, 42, 44, 48, 49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 47, 51

More evidence that Empire belongs to 1957 is that the new clump of titles from the beginning of that year uses the slug line at the bottom of the back panel (33) and this time prints it in the correct order although the inexplicable extra space now appears between “science” and “fiction.”

Attractions, James Blish’s The Seedling Stars, and Murray Leinster’s Colonial Survey, the first three titles registered in 1957, all share this back panel. Four titles from later in 1957 would join them on the listing. Another handful of titles are retired: Sixth, Sands, Robots, City, Complete, Quest, and Terror. Reprieve is oddly omitted; oddly since it will return immediately after.

Merril’s anthologies lose their apostrophe starting on this panel, from The Year’s Greatest to The Years Greatest. They would never get it back until the very last back panel although the panels went through half dozen or so iterations between.

Title(s) on: Two Sought Adventure; SF ’57: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction; Earthman’s Burden; The Return of Conan; They’d Rather Be Right; Methuselah’s Children; Undersea City

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 36, 40, 42, 44, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 47

Indeed, the only difference between this back panel and the one that would be used on the next seven books is the inclusion of Reprieve and the removal of the Outstanding Science Fiction Books tag. That back panel (34) lasted for more than year and finally catches up with the books already listed: Fritz Leiber’s Two Sought Adventure, Judith Merril’s SF: ’57: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction, Poul Anderson and Gordon Dickson’s Earthman’s Burden, Robert E. Howard’s, The Return of Conan, Mark Clifton and Mack Riley’s They’d Rather Be Right, Robert A. Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children, and Frederick Pohl and Jack Williamson’s Undersea City. That covered books issued well into 1958.

Title(s) on: Methuselah’s Children variant

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 36, 40, 42, 44, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 47

Methuselah’s had the largest first printing of any Gnome title, befitting Heinlein’s reign over the field in the 1950s. Greenberg bound 5000 of them for the April 1958 release and quickly realized that they weren’t enough. “Less than a year later,” according to CHALKER, he bound the other 2500. He must have planned to simply reprint the dust jacket but he was in the middle of moving his office to Hicksville, the most ironically-named home for a science fiction publisher imaginable. Hicksville was on Long Island, 30 miles east of his former Manhattan office but the Long Island Rail Road ran through it and the Northern State Parkway and the Long Island Expressway bordered the town for easy access. To play safe, the back panel (35) of Methuselah’s binding left off both addresses and just read The Gnome Press Inc. New York. No fewer than four differently-colored variants bear this truncated address, in black, red, and green boards and gray cloth. CURREY says that the red and green boards carry 32-title back panels. I have both and each has the identical 35 titles to the others. No search of the internet brings up a single image of a 32-title dust jacket. Nor does his unverified red cloth variant appear. I’m going out on a limb and sticking with the two known and verified variants only.

Title(s) on: The Shrouded Planet; The Survivors; SF: ’58: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy; Tros of Samothrace; Purple Pirate

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 36, 40, 42, 44, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 47, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75

If Greenberg was uncertain of his address late in 1958, then the move must have been made in 1958. If only if were that simple. The next back panel (36) has the Hicksville address but is otherwise identical – and it first appears on Robert Randall’s The Shrouded Planet, which was registered on September 25, 1957. The first newspaper mention I can find is from February 2, 1958 so a possibility exists that it was held back for the move, although that’s before Methuselah’s was registered. Otherwise the listing contains titles from 1958 and 1959: Tom Godwin’s The Survivors – which was also registered before Methuselah’s, Judith Merril’s SF: ’58: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction, and two books by Talbot Mundy, Tros of Samothrace and Purple Pirate.

What breaks logic is that none of these five books are part of the title listing, nor was Methuselah’s. How could Greenberg continue to use a back panel that didn’t mention his coup in publishing a Heinlein title at a time when no other small press had that good fortune? The two Mundy books were to be a start of a start of a new imprint, Fantasy Classic Library. How could he not mention that on the back of those books or the books surrounding them? Purple was not published until 1959 – after a new back panel had been introduced. Why not use that new one instead so at least the connection back to Tros would be made? Just as Attractions looked 17 months forward for no reason, Purple looked 17 months backward to the detriment of sales.

Title(s) on: Sands of Mars variant

Titles displayed: 5, 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 21, 25, 28, 29, 31, 33, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 41, 43, 45, 47

Greenberg had another chance to make a useful change at around the same time. Sands continued to sell consistently and earned a second binding of the second printing with a third back panel. This back panel (37) looks superficially similar to the previous one but in fact has numerous changes. Three titles are added: Clarke’s Sands and Prelude and Heinlein’s Sixth, with his middle initial corrected. Children is omitted. Star Bridge remains but is moved to the end, suddenly credited correctly to Williamson and Gunn, rather than Gunn and Williamson as all previous back panels had had it. A different order for Greenberg’s anthologies is presented. The address is confined to one line instead of two.

The reappearance of Sands and Prelude after long absences need explanation. CHALKER states that this Sands binding was done in 1957, which fits the title list, but puts the last binding for Prelude in 1955. Clearly that should be 1957 as well. Sixth’s reappearance is utterly mysterious. No source mentions a second printing or binding; no source mentions variant boards. Did Greenberg find a stack of unopened boxes in the back of an office when he moved?

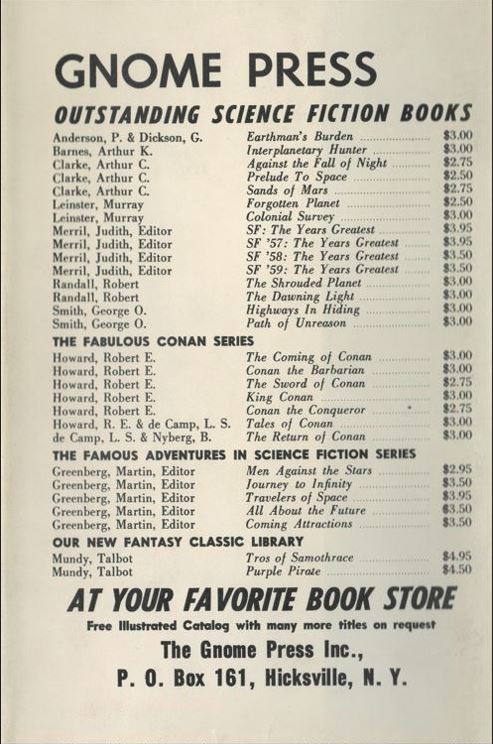

Title(s) on: Starman’s Quest; The Path of Unreason; SF: ’59: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction; The Dawning Light; The Bird of Time; The Menace from Earth; The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag; Agent of Vega; The Vortex Blaster

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 21, 25, 28, 31, 33, 36, 39, 42, 44, 46, 53, 55, 56, 57, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 71, 72, 74, 75, 76, 77

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 54, 58, 60, 62, 67, 68, 69, 70, 73, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82

When the new back panel (38) appeared in 1959 on the back of Robert Silverberg’s Starman’s Quest, no follower of publishing could imagine that the same back panel would be used on eight more titles stretching well into 1960 – none of which were listed. Robert Randall’s The Dawning Light is there and George O. Smith’s The Path of Unreason, but not Judith Merril’s SF: 59: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction, Wallace West’s The Bird of Time, two collections of Robert A. Heinlein short stories, The Menace from Earth and The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag, James A. Schmitz’s Agent of Vega, or Edward E. Smith’s The Vortex Blaster. That’s correct. Greenberg now had three titles by the top writer in the field and failed to mention any of them.

By pulling out “The Fabulous Conan Series” and “The Famous Adventures in Science Fiction Series” to add to “Our New Fantasy Classic Library,” Greenberg inadvertently revealed how thin the Gnome backlog had become. The Outstanding Science Fiction Books on the back panel of Path of Unreason were reduced to three classics each by Asimov and Clarke, four anthologies, one of which hadn’t appeared, and eight books by four authors and a team, one of which also hadn’t yet appeared. Meanwhile, previous released books like Undersea would never be on a back panel until Gnome’s very last book four years in the future, and Survivors and Rather not even then. Rather was a Hugo winner, which made it a prize. It had a reprint (retitled The Forever Machine) as a Galaxy Novel mass market paperback, but that line never took off, making it effectively invisible. Survivors was Godwin’s only novel available at the time and it wouldn’t appear in paperback (as Space Prison) until 1960. Undersea was the last of a trilogy, and its paperback didn’t appear until 1971. They may not have been on Heinlein’s level but each had real value deserving of promotion. Mentioning them should have been automatic. Much the same can be said for books that carried this back panel. Starman’s Quest, Bird, Agent, and Vortex would not be seen until that last book, along with the two Heinlein collections.

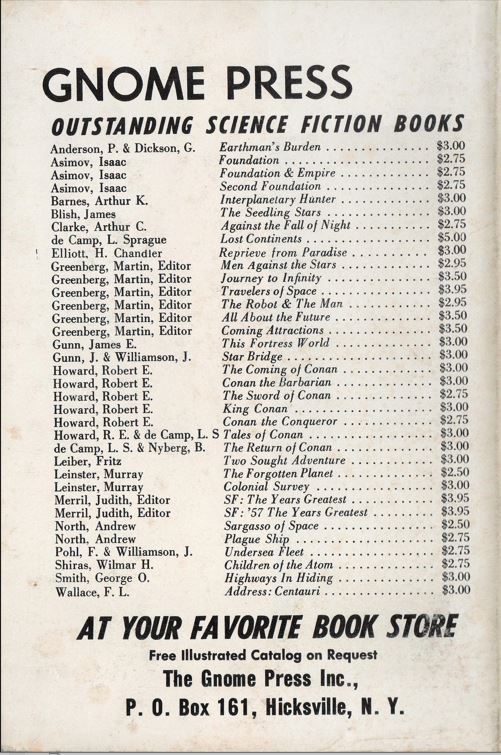

Title(s) on: Drunkard’s Walk; Invaders from the Infinite; Foundation and Empire variant

Titles displayed: 6, 12, 16, 19, 21, 25, 28, 31, 33, 39, 42, 46, 53, 55, 56, 57, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 69, 71, 72, 74, 75, 76, 77

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 54, 58, 60, 62, 67, 68, 70, 73

From the inexplicable we vault to the hallucinogenic. The last gasps of the Gnome Empire include the hardcover version of a paperback original, Frederik Pohl’s Drunkard’s Walk, and the inheritance of John W. Campbell’s Invaders from the Infinite from Fantasy Press, even closer to death than Gnome. The second binding of the second state of Empire also received this back panel (39).

The Conan series shrunk to four titles, as did Greenberg’s anthologies. Replacing them are no fewer than three Heinlein titles, those completing his Future History. Another coup. The Man Who Sold the Moon, The Green Hills of Earth, and Revolt in 2100 had been published by another small press, Shasta: Publishers, in 1950, 1951, and 1953. Shasta effectively died then and Heinlein took back his rights. With Shasta dead, Heinlein offered the books to Greenberg. Putting the Future History together would be a glistening prize for Gnome. This back panel devalues that prize in several ways. It is nearly incomprehensible that anyone would list three famous books of future speculation, the hardest of hard science fiction, under the Fantasy Classic Library imprint or group them alongside Mundy’s historical fantasies. Nor is there any indication that unlike every other title on the back panel, these books had not yet been published, although Greenberg had an addiction to putting unpublished books on his back covers. Moreover, Greenberg had indeed published two original Heinlein collections – but didn’t bother to mention them. Such lost opportunities.

Title(s) on: Gray Lensman

Titles displayed: 6, 9, 12, 18, 19, 21, 28, 31, 36, 39, 42, 44, 46, 53, 55, 56, 57, 59, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66, 71, 72, 74, 75, 76, 77

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 58, 60, 62, 67, 68, 69, 70, 73

Greenberg published a second volume rescued from Fantasy Press, Edward E. Smith’s Gray Lensman. The rogue Heinlein titles are thankfully removed on this back panel (40). No mention of them is made in William Patterson’s biography, but his reaction must have been volcanic. For reasons unknown, his Methuselah’s is also missing, along with the entire Foundation trilogy. Otherwise, none of the missing titles rate a mention but some older titles, Travelers and three additional Conan books, make a mysterious reappearance.

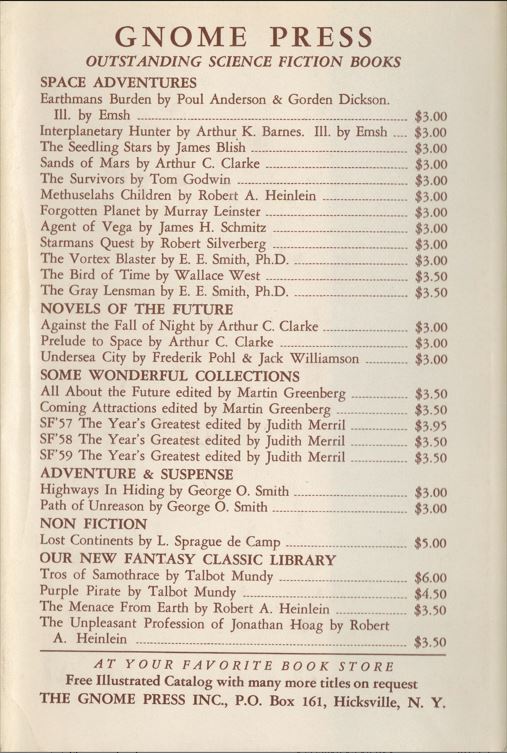

Title(s) on: The Philosophical Corps

Titles displayed: 21, 31, 39, 40, 42, 46, 55, 57, 59, 60, 63, 64, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 85

Missing: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 41, 43, 44, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 56, 58, 61, 62, 65, 66, 67, 77, 83, 84

The last book Gnome released confounds utterly. Greenberg owed his printer at least $100,000 and stacks of unbound books could be found everywhere. Getting new product out the door might at least generate a cash flow, but that cash could flow only if the new product was a guaranteed success, with name value that would lure buyers. Instead, he released Everett B. Cole’s The Philosophical Corps. Cole was certainly a pro, but not a name to conjure with. He sold about a dozen stories to Astounding during the 1950s, including The Best Laid Plans, a novel serialized in 1959 so it was a new and untouched property. But no. Greenberg went back a decade to his very first story “The Philosophical Corps” and had him rewrite that and two sequels into a novel. Were Cole fans pleased? Probably not. There was a third sequel that didn’t make the book, leaving the series incomplete for the next fifty years. As for cash flow, the book might as well have been thrown into the ocean. It didn’t receive a review in an f&sf magazine until April 1963 and by that time Gnome was defunct. A newspaper mention in June 1962 is the only evidence available to pin down a release date. The copyright date is 1961 and the registration lists it as In notice: 1961, but it could have been delayed until 1962.

Many of the recent tiles, dating back to 1958, make their first and only appearance on this back panel (41): Tom Godwin’s The Survivors, Robert A. Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children, The Menace from Earth, and The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag, Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson’s Undersea City, Robert Silverberg’s Starman’s Quest, Wallace West’s The Bird of Time, James A. Schmitz’s Agent of Vega, Edward E. Smith’s The Vortex Blaster and Gray Lensman. That would be small consolation to the titles that wound up never appearing on a single back panel. Still omitted are Frederik Pohl’s Drunkard’s Walk, John W. Campbell’s Invaders from the Infinite, and, missing since 1957, Mark Clifton and Frank Riley’s Hugo-winning They’d Rather Be Right.

In some ways, having people see the book might have been worse than their not seeing it. The only way to explain the back panel – completely redone at long last – is to suppose that Greenberg intended it as a test to hire a copywriter but mistakenly published it rather than the corrected product. How many can you find?

No fewer than three titles are listed with genitives that required apostrophes: Earthman’s, Methuselah’s, and Starman’s. None of them show any. Where did they go? They slid down the page to Merril’s anthologies. Those properly had colons in their titles, SF: 57, SF: 58, and SF: 59, but are represented here as SF’57, SF’58, and SF’59. The Path of Unreason had always been presented without the “The” but The Forgotten Planet had always included it – until now. Where is it? Slipped in front of Gray Lensman, where it absolutely doesn’t belong.

“Ill. By Emsh” – illustrated by Ed Emshwiller – is appended to Earthman’s and Interplanetary. He indeed did the interior illustrations for Interplanetary but not for Earthman’s, which was Edd Cartier’s work. How could such a gigantic mistake be made?

The section listings also have their share of wonders. “Space Adventures” has the authors in alphabetical order, except that Wallace West’s The Bird of Time somehow snuck in between Edward E. Smith’s The Vortex Blaster and The Gray Lensman. Or is he E. E. Smith, Ph.D. as this panel has it? The books credit him as Edward E. Smith, Ph.D. on every occasion, both inside and on the dust jacket – except for the cover of Vortex where he is E. E. Smith, Ph. D. Normally a book’s interior controls the author’s name, not the cover. (If covers ruled then James H. Schmitz would have been James A. Schmitz since his cover has that horrendous typo.) Even the copyright registration for Vortex lists him as Edward E. Smith (sans Ph.D.). If this were a copyeditors’ quiz, would “all of the above’ have been an acceptable answer?

The sorting of the titles into these categories is random enough to bring a pleasant fizz to the brain. Virtually all of Gnome’s titles could be classified as “Space Adventures,” “Novels of the Future,” or “Adventure & Suspense.” Why are George O. Smith’s titles alone in that last category? Why is Prelude, the story of the first rocket to the Moon, set in near-future 1978, a “Novel of the Future,” when Sands, set later in time when a Mars colony exists, not one? Why is Non Fiction typeset as two separate words? Why oh why are Heinlein’s Menace and Profession listed as part of the New Fantasy Classic Library when they weren’t released with that name and the former title is mostly science fiction rather than fantasy?

One last why. Why is Tros listed at $6.00 when no book marked with that price has ever been found?

As always with Gnome, we end on an unanswerable question.