Comments

Judith Josephine Grossman (1923-1997) was part of the generation of New York City f&sf enthusiasts that circulated through the fan group known as the Futurians, along with Gnome authors Frederik Pohl, James Blish, and Isaac Asimov, Gnome co-founder David Kyle, and others such as C. M. Kornbluth, Damon Knight, and Donald A. Wollheim. All the Futurians wanted to write f&sf; most succeeded to some degree, many also went on to become editors.

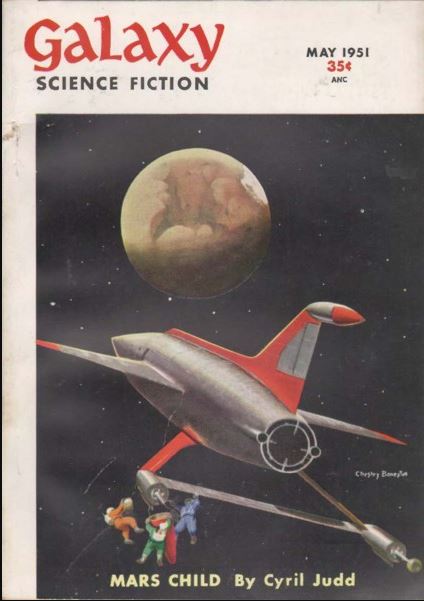

Judith married Dan Zissman in 1940. Except for some fanzine editing under the name Judy Zissman, Judith Merril became the name she was known by professionally and in fandom, a tribute to Merril, the daughter she had with Zissman. She credited Theodore Sturgeon, her lover in 1947, for suggesting the name. Even pseudonyms didn’t really hide her true identity: when she and Kornbluth wrote two novels under the name of Cyril Judd, their true identities were revealed in the pre-book publication Galaxy serialization of Outpost Mars: Judd for Judith, Cyril as Kornbluth’s real first name.

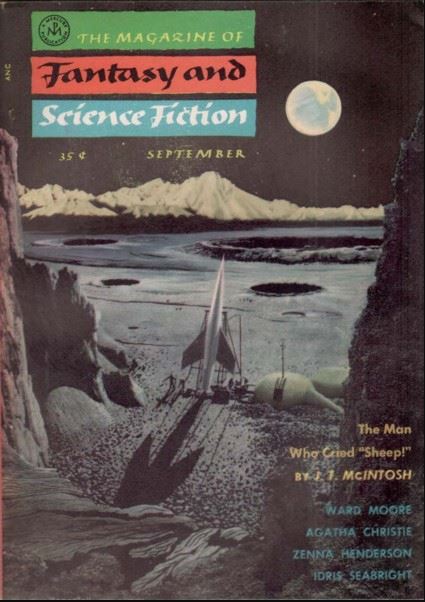

Never a prolific writer (although one good enough that Marty Greenberg included one of her stories in his Journey to Infinity anthology), Merril started editing anthologies in 1950, when she was married to Pohl. (Partner-switching was endemic in the tiny world of science fiction writers. After divorcing Pohl she went on to live with Walter M. Miller Jr. They had separated by the time she included a story of his in this volume and he was too strong a writer to be tarnished by innuendo.) Starting an annual best-of-the-year series was not an original idea in 1956 but she read widely and was determined to expand the vision of the field past the standard genre magazines. The name she chose for her series was equally a break in convention: almost all early best-of-the-year anthologies had only science fiction in their titles. Contemporary critics, Knight and Blish notably among them, adamantly insisted that “science fiction” must contain some science, preferably a new notion befitting the literature of ideas. Pure fantasy and the type of mainstream stories now called slipstream might be acceptable in their own domains but shouldn’t sully the purity of the genre. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F&SF) had worked hard to make this stance obsolete since it took on that name in 1950 and by 1956 its view of the field overpowered John W. Campbell’s Astounding as the home for the best of what the genre was capable of. Greenberg would be a devout Campbellian until the end. It’s to his credit he took on Merril and an anthology stuffed with stories not to his taste.

Gnome Notes

Nor did Greenberg slouch on the production. He gave the book special treatment, so much so he overflowed the space on the front flap to flaunt his efforts:

The finest book we could make – extra-large, on heavy paper, finely bound, designed for your permanent library as the first of a series of matched volumes of each [no period in original]

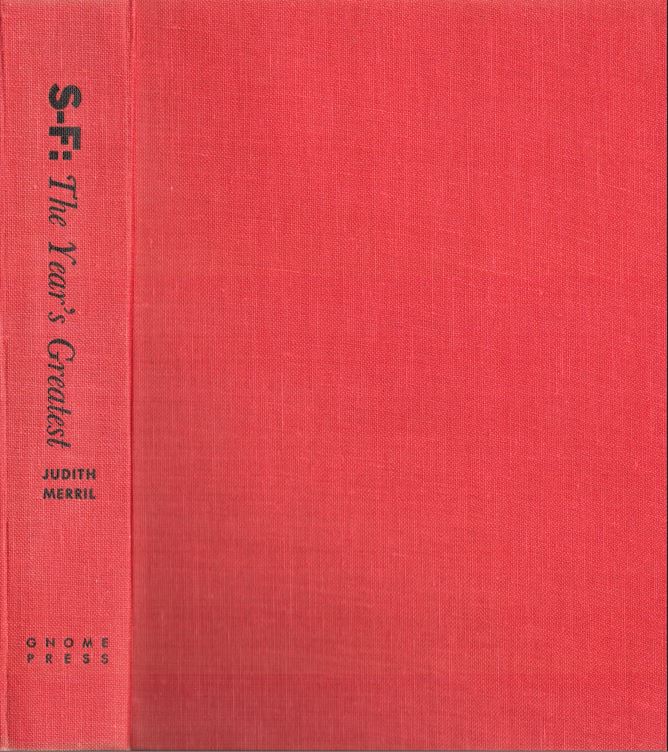

Of each what? We’ll never know: the sentence cuts off there. Having undercut his boasting by sloppy copyediting, Greenberg proceeded to make promises he couldn’t keep. True, the book is extra-large. Gnome books were made to a standard 5 ½” width and 8 ¼” height. SF:56 is a full half-inch wider. The red cloth binding is nice, though no more so than any other of their cloth editions (and inferior to the half-cloth backing Greenberg gave to his own anthologies), but the red boards variant looks as cheap as it feels. (Greenberg didn’t mention that the paperback publisher Dell is the actual originator of the series and so set the type, gifting him with books that cost much less than usual, allowing him to splurge a bit on the niceties.) The heavy paper was of a higher grade than the inexpensive, quickly-browned pulp he typically used in 1956. One wonders what Arthur K. Barnes, whose Interplanetary Hunter immediately preceded Merril, thought about his much lower quality production. Finally, the set of matched volumes was never to be. The next three Merril anthologies were fixed at 5 ¾” x 8 ½”, matching one another but not either the original volume or the standard Gnome. At least the cover art by Ed Emshwiller on this first book is more alluring than the work of W. I. Van der Poel on the next three volumes.

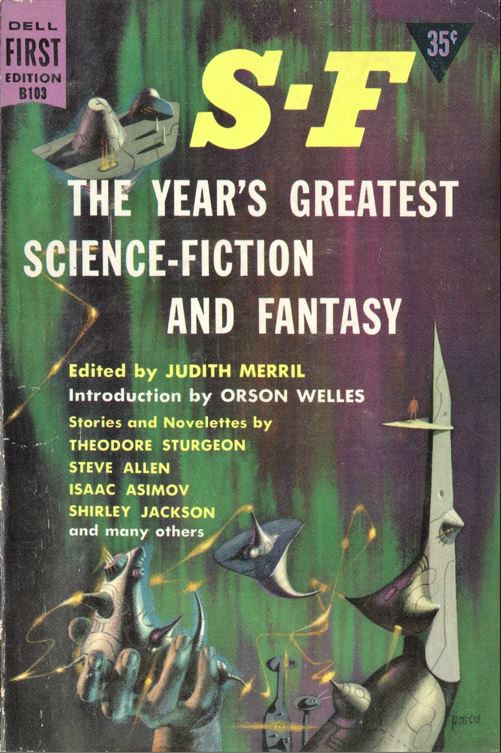

It would not be Gnome without a mystery and this one strikes at the heart of bibliography: identifying the true first edition. Merril would publish the first four of her twelve Year’s Greatest anthologies in hardback with Gnome. Each was published “simultaneously” by Dell Publishing Co., the paperback giant, according to both CURREY and William H. Lyles in his monumental Dell Paperbacks, 1942 to Mid-1962, A Catalog-Index. Indeed, all four match in their pagination, indicating that Dell and Gnome used the same plates. This first volume appeared as Dell B103, part of its Dell First Editions line. Leaving aside the misleading aspect of a paperback “First Editions” line also seeing publication in hardback, the claim of “simultaneous” publication was probably more an intention than a reality. Lyles gives the date of the Dell paperback release as April 1956. The Gnome hardback was published… when?

The entry in the ISFDB says of the Dell edition:

According to L. W. Currey, this is the first edition, published simultaneously with the Gnome hardcover. Bleiler agrees but lists the Gnome edition first. The Cole Checklist [A Checklist of Science Fiction Anthologies, by W. R. Cole, 1964] says it was published in May 1956, two months before the Gnome hardcover.

Whether April or May is correct, Dell B103 appears to be the true first edition. For inexplicable reasons, the book is not listed in the Catalog of Copyright Entries. Dell printed a healthy 208,000 copies in its only American edition and added 12,000 more for its Canadian edition.

Nobody at Gnome would ever settle on a consistent punctuation for the series titles. The front cover, spine, and back panel of this volume’s dust jacket use SF: while the title and half-title pages, the spine on the boards, and the front flap all use S-F: with an unexpected hyphen. The back panel refers to the book as S-F: The Year’s Greatest Short Science Fiction and Fantasy, with an interpolated “Short.” The Dell paperback always hyphenates the “S-F.” Lyles notes that the book was planned to have the title “The Year’s Best,” but does not give a reason for the change.

In the continuing series of unbelievable Gnome typos, Avram Davidson’s name being misspelled Arvan Davidson on the front jacket cover must rank high on the list. Shirley Jackson’s name is also completely missing from the author list, under any spelling.

Reviews

Floyd C. Gale, Galaxy Science Fiction, February 1957

[S]ome of the finest science fiction of all time is being produced and published right now. Miss Merril’s book is indication enough of that. … A cautionary note: … it is a collection of unswervingly personal favorites.

J. Francis McComas, The New York Times Book Review, November 18, 1956

[A] gallant few have faithfully observed Miss Merril’s own rule, that a writer’s “first big job is entertainment.” The majority of her contributors seem to have ignored that basic qualification entirely.

Contents and Original Publication

• story introductions, unsigned, presumably by Judith Merril (original to this volume).

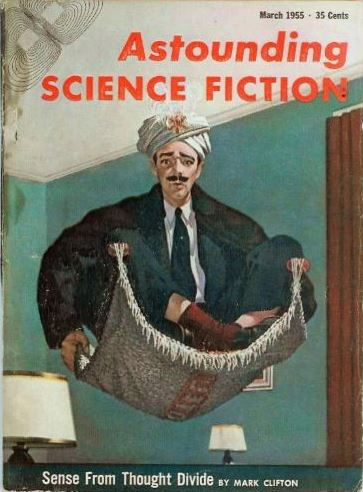

• R.R. Merliss, “The Stutterer” (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1955).

• Avram Davidson, “The Golem” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1955)

• Robert Abernathy, “Junior” (Galaxy Science Fiction, January 1956).

• James E. Gunn, “The Cave of Night” (Galaxy Science Fiction, February 1955).

• Walter M. Miller Jr., “The Hoofer” (Fantastic Universe, September 1955).

• Theodore Sturgeon, “Bulkhead” (Galaxy Science Fiction, March 1955 as “Who?”).

• Mark Clifton, “Sense From Thought Divide” (Astounding Science Fiction, March 1955).

• Zenna Henderson, “Pottage” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, September 1955).

• Algis Budrys, “Nobody Bothers Gus” (Astounding Science Fiction November 1955, as by Paul Janvier).

• E. C. Tubb, “The Last Day of Summer” (Science Fantasy, February 1955).

• Shirley Jackson, “One Ordinary Day, With Peanuts” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, January 1955).

• Willard Marsh, “The Ethicators” (If, August 1955).

• Mildred Clingerman, “Birds Can’t Count” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 1955).

• Jack Finney, “Of Missing Persons” (Good Housekeeping, March 1955).

• Isaac Asimov, “Dreaming is a Private Thing” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, December 1955).

• Damon Knight, “The Country of the Kind” (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, February 1956).

• Steve Allen, “The Public Hating” (The Blue Book Magazine, January 1955).

• Henry Kuttner &. C.L. Moore, “Home There’s No Returning” (No Boundaries, collection by Henry Kuttner &. C.L. Moore).

• Judith Merril, “S-F 1955” (original to this volume).

• Judith Merril, “The Year’s S-F: A Summation by the Editor” (original to this volume).

• Judith Merril, “Honorable Mention” (original to this volume).

Bibliographic Information

S-F: The Year’s Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy, Edited by Judith Merril, 1956, no copyright registration, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 56-8938, title #56, back panel #31, 352 pages, $3.95. 3000 copies printed. Hardback. Jacket design by Emsh. “First Edition” stated on copyright page. Manufactured in the United States of America. Printed by: Noble Offset. Binding by: H. Wolff. Back panel: 36 titles. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

Variants, in order of priority

1) (CURREY A) Red cloth, spine lettered in black.

2) (CURREY B) Red boards, spine lettered in black.

True first edition

Dell First Edition, B103, (New York: Dell Publishing Co), First printing – April 1956.

Images