Comments

Leigh Brackett (1915-1978) is an unusual case of a core f&sf insider becoming better known outside the genre. She grew up reading both f&sf and crime fiction and wanting to write both or either. Discovering the fan scene in Los Angeles pushed her toward the former when Henry Kuttner brought her to a meeting of the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society (LASFS). In 1940 she became yet another who made their first sales to John Campbell at Astounding. The association lasted only for one more story; Brackett wrote what’s been described as romantic space opera – as devoid of science as the stories of her friend and later collaborator Ray Bradbury, hardly Astounding material.

Much is made of her ambiguous first name in an era whose practitioners were virtually all men. Editors had no qualms about buying from her. Responding to a letter from a female fan (they also existed) about an earlier Brackett story, Planet Stories Editor W. Scott Peacock responded in the May 1943 issue with the weird comingling of admiration and condescension conferred upon women that often contaminated the entire field of literature.

Leigh Brackett is not a man. And poor male that we are, we don’t even profess to guess what any (except you, of course) woman is talking about. All we know, is that she us destined to become one of the finest science-fiction writers of this generation.

Emancipation . . . .!

Digression

I could find no biographical information on W. Scott Peacock, so I’m going to insert a couple of paragraphs here. I’m sorry for the interruption, Mrs. Hamilton – which is how Brackett termed herself when not being an author – but this page has at least a slight rationale for such inclusion and will be findable on a search.

Wilbur Scott Peacock was born in 1915. No hint or where or what his parents were like, although he said he had a younger brother and sister. He had the usual potpourri of jobs and the requisite stint in a jail somewhere for some unknown reason before turning to freelancing. The first story I can find appeared in the October 1938 Detective Tales. He claimed in 1943 to have written an improbable 400 stories and seven novels under a variety of names. Databases yield three names and a respectable 70 short titles and nothing else. Perhaps none of the rest of the names ever became public, or perhaps he exaggerated, not unheard of for a pulp writer.

Peacock was supposed to be one of the million-word-a-year elites in pulp, but still sought the security of a full-time job. Another wunderkind, he, like John W. Campbell and Ray Palmer, became a science fiction magazine editor at the age of 27. He took over Planet Stories as of the August 1942 issue. He soon added the editorship of Jungle Stories, to which he had regularly contributed the Ki-Gor – King of the Jungle stories as by John Murray Reynolds, and also three additional pulps all for the vast Fiction House company. (To the consternation of future bibliographers and historians, he edited under the name of W. Scott Peacock but wrote as Wilbur S. Peacock.)

Fan and future magazine editor Larry Shaw visited him – all the New York editors provided easy access to fans and budding writers – and was awed that “Peacock does all the work on those five magazines – editing, rewriting, copyreading, proofreading, more proofreading, dummying–everything except the actual printing.” From the Fiction House office he went home to write more pulp.

Peacock stopped editing at the end of the war, writing full time, growing ever more successful as he rose through the pulps to mainstream magazines and television, until those venues were closed to him. He eventually ended up editing magazines for American Art Enterprises, the parent company of Brandon Books, whose science fiction line was edited by … Larry Shaw, from an office down the hall. Shaw is the source for almost all the information available on Peacock. His Science Fiction Review obituary on Peacock’s death in 1979 gives more on his later career than all other sources combined.

When he became a regular at BLUE BOOK, he quit to freelance and, with this as a cash base, plugged away until he had broken everyone of the biggest slick magazines – – POST, COLLIER’S, MC CALL’S, MC LEAN’S (of Toronto). In the late 40s, he went west to write scripts for the Hal Roach TV mill, churning out a mighty volume of “Cisco Kid” scripts and creating such series as “Sheena of the Jungle”, “Benvenuto Cellini”, and “Francois Villon” (the latter series, an old BLUE BOOK standby [that Peacock wrote], was an early TV vehicle for Errol Flynn.

Blacklisted in TV in the 50s, he went back to editing for a string of men’s magazines, but had returned to his first love — the writing of sf — in his last years, selling a series of shorts to no less a market than PLAYBOY. [transcribed exactly as in original]

Unfortunately, few of these claims can be confirmed. I can only say that Peacock wrote many stories for Blue Book and five episodes of The Cisco Kid, along with a half dozen random episodes of other 1950s series. He did appear in Esquire in 1951, though, when it was also a leading mainstream source of fiction.

When he died he was living in Los Angeles, so he had left the New York magazine scene but when and why are not findable. Let’s hope that this compilation inspires others to fill in the many holes in Peacock’s biography.

End Digression.

Her forte was descriptive flair and imagination. When she finally sold a few mysteries, one featured a murder by sabre-tooth tiger. A hard-boiled novel, No Good from a Corpse, followed in 1944. For once, a Hollywood legend is true, or at least can be traced to a source. Hedda Hopper reported in her gossip column that Howard Hawks read the book and was so impressed that he told his agent, “This fellow would make a good screenwriter for The Big Sleep; get Mr. Brackett for me.” Hawks didn’t balk when a young woman showed up to work. Brackett always claimed that being a woman was never an impediment for her in writing, either in genre or in Hollywood. She had already co-written a quickie for Republic, the irresistibly-titled The Vampire’s Ghost, and would phase out of genre writing in the 1950s to do more screenwork. (Her 1955 novel The Long Tomorrow was the first book by a woman to get a Hugo nomination.) She got credit on several John Wayne movies, Robert Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye, and a few crime dramas and television shows. In 1977 she was asked to write her first science fiction script, a sequel to Star Wars. She turned in a first draft before she died of cancer in early 1978. The final version of The Empire Strikes Back retains some of her concepts but was completely rewritten, first by George Lucas and then Lawrence Kasdan. Nevertheless her name remained in the credits, so she gets the fame that accrues to all associated with the blockbusters.

Brackett met Edmond Hamilton, one of the early kings of space opera, at the office of their mutual agent, Julius Schwartz, in 1940. Their first date was to a LASFS meeting. The attraction was instant – Brackett even named the hero of No Good from a Corpse Edmond – but the war intervened and they did not marry until 1946. They envied the ability of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore to collaborate, but couldn’t pull off the trick themselves. However, Brackett ghostwrote several Captain Future stories published under Hamilton’s name in the 1950s, including the one in the March 1951 issue of Startling Stories that also contained “The Starmen of Llyrdis,” the source for this novel. Was the woman on the cover a glamorized version of Brackett herself? Looking at the picture above, I’d say yes.

Brackett is quoted in R. Reginald’s Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature with this encomium to the small, yet wonderfully embracing, world of early fandom:

Being a science fiction writer is bountifully rewarding in ways other the financial… lifelong friendships, the pleasure of belonging to a family that stretches around the globe, so that wherever one goes, one has friends; the pleasure, which does not exist in any other field, of being able to stretch one’s imagination ‘beyond the farthest star.’

Gnome Notes

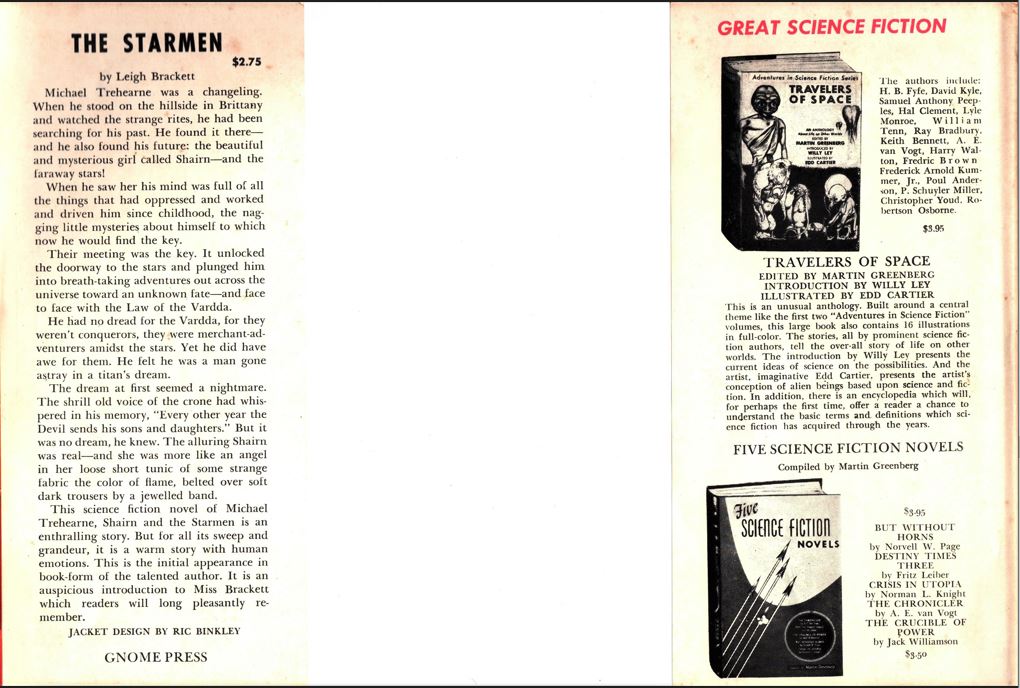

Leigh Brackett expanded the story for the Gnome version while Greenberg shortened the title. He apparently didn’t like alien names in titles: not a single title has one. Other publishers must have felt differently. “Of Llyrdis” was reinstated for all later paperback editions.

Greenberg referred to her as “Miss Brackett” on the flaps, a forthright signaling of gender for an author with an ambiguous name. In personal life, people referred to her husband and her as Ed and Leigh Hamilton but she retained the Brackett identity for all of her writing career.

The jacket flap says “This is the initial appearance in book-form of the talented author,” oddly untrue. The genre was resolutely insular in those days. Other genres were simply written out of reality. Even so, the claim is a reminder of how few books the vast majority of the now familiar and well-thought-of names had ever published pre-Gnome.

Greenberg snagged the first or second book by Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, George O. Smith, Clifford D. Simak, Raymond F. Jones, Hal Clement, James Gunn, and James H. Schmitz, and was responsible for a large percentage of the entire book careers of Wilmar H. Shiras, F. L. Wallace, H. Chandler Elliott, William Morrison, Arthur K. Barnes, Mark Clifton, Tom Godwin, Wallace West, and Everett B. Cole.

Reviews

George O. Smith, Space Science Fiction, May 1953

It is readable because Leigh Brackett is a smooth, accomplished writer. But the plotting and the background make me wish Leigh Brackett would get back to Earth and surround herself with characters that look, act, and stay human.

Villiers Gerson, New York Times Book Review, November 23, 1952

Leigh Brackett, one of science fiction’s few stylists, has here written a somewhat over-picturesque novel. Nevertheless, it is well above the average s-f story and is probably one of the best releases that Gnome Press has put out to date.

Contents and original publication

• Chapters 1-22 (Revised and expanded from “The Starmen of Llyrdis,” Startling Stories, March 1951).

Bibliographic Information

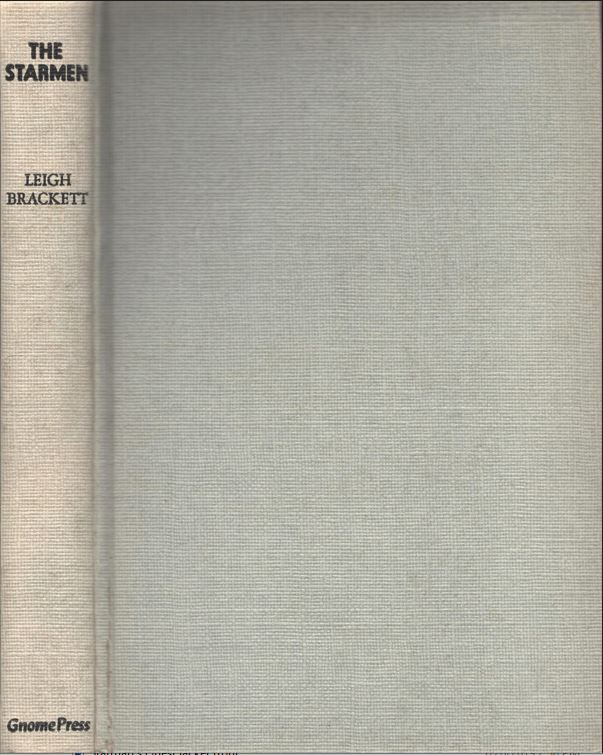

The Starmen, by Leigh Brackett, 1952, copyright registration date 15Nov52, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number not given [retroactively 52-13840], title #26, back panel #21, 213 pages, $2.75. 5000 copies printed. Hardback, gray boards, spine lettered in black. Jacket Design by Ric Binkley. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Printed in the United States of America. Back panel: 26 titles. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th Street, New York 3.

Variants

None known.