Comments

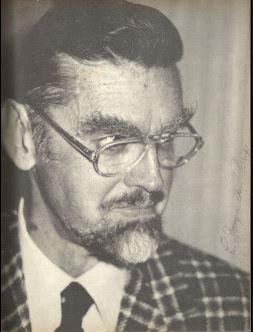

Lyon Sprague de Camp is oddly forgotten today but in the late 1940s he was among the handful of top f&sf writers in the field. Everybody wanted him. He’s the only author to have a publishing flush: all five of the top small presses of the day, Gnome, Shasta, Prime Press, Fantasy Press, and Fantasy Publishing Company Inc. (FPCI), published him in hardcover between 1948 and 1951. Readers of those other presses would see an ever-growing list of “other titles by” in every book, no matter who it was published by. Those who received the 1951 FPCI edition of his The Undesired Princess probably thought nothing of seeing his early Gnome titles The Carnelian Cube and The Castle of Iron as well as a listing for Lost Continents under Non-Fiction.

Except that Lost Continents wasn’t published until 1954.

Since science fiction has a miserable record of prescience, a story must be told to explain this. The story of Prime Press almost duplicates that of Gnome. A group of long-term Philadelphia fans saw an opportunity in 1948 and started a small publishing company. They had some hits – the first books by Theodore Sturgeon, Lester del Rey, and George O. Smith – and some misses, and a connection with de Camp since he spent the war years working at the Philadelphia Naval Yard. In 1949 they reprinted his Lest Darkness Fall and geared up to print his magnus opus, Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature, a thick and awesomely erudite tome covering every mention of Atlantis since Plato, along with Plato’s family tree and nearly 100 small-print pages of other appendixes, notes, bibliography, and scholarly apparatus.

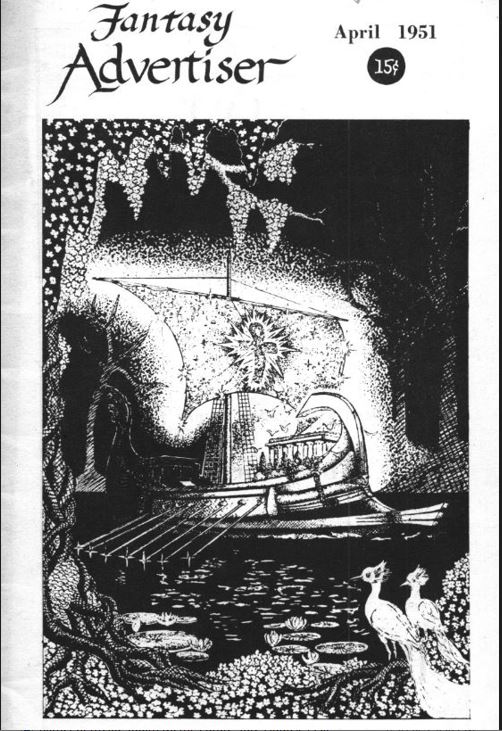

The years rolled along and the field waited. Not on de Camp – he had finished the book in 1948 – but on Prime. Tantalizing hints appeared. The complete table of contents appeared in the fanzine Orb in 1950. Willy Ley actually reviewed the book for the April 1951 issue of the fanzine Fantasy Advertiser, giving the publishing date as “1951; (approx.).”

Prime issued a 16-page advertising brochure in 1951, containing a sampling of pages from a seemingly completed printing. The book, it said, would appear in April 1951 and the order form listed it at a pricey $4.50. At some point copies got corrected to read Fall 1951 and a staggering $6.00 price tag. The brochure must have been the impetus for the FPCI mention but 1951 passed bookless.

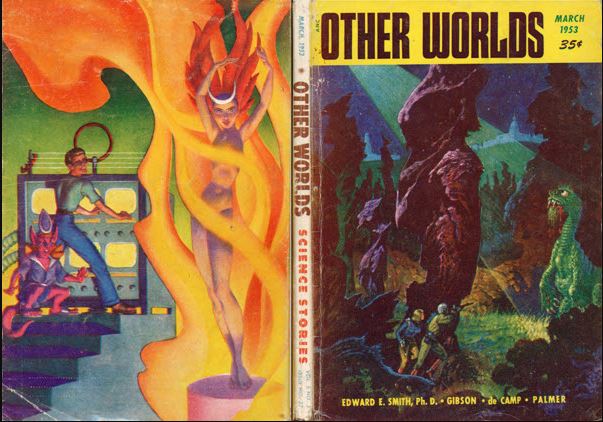

Eager readers received more tangible proof of existence in 1952. Ray Palmer, now editing the decidedly third-rate magazine called Other Worlds, desperately needed serious content to balance his obsessive printing of Richard Shaver’s purportedly true tales of … the lost continent of Lemuria. Why de Camp allowed his polymathic research to run literally adjacent to Shaver can only be explained by mundane mercantile reasons. He hadn’t seen a penny for this work in four years and he and his wife had had a second child in 1951. His expectations must have remained high. Each of the nine chapters to run consecutively from October 1952 through July 1953 (except for April, where it was crowded out by a complete novel) were carefully labeled as “slightly condensed” from Lost Continents, Prime Press, 1952. But. I haven’t gone through every page, but the chapters I checked seemed to be identical to the Other Worlds text. This implies that the Prime version was longer, but Greenberg used their printed pages. What could possibly have been cut out?

Nevertheless, in reality Prime Press was bankrupt in 1952. No one knew that at the time, to be sure. Only when one of the founders died unexpectedly in March 1953 did the rest of the company learn of the bills he had not paid. Their creditors forced the company into bankruptcy. Many planned books, including yet another de Camp title, disappeared for years. Prime’s creditors forced a sale of its assets. Marty Greenberg walked away with the big prize: 3000 – or perhaps more – fully printed but unbound copies of Lost Continents.

Gnome Notes

Many unkind things can and have been said about Greenberg, but nothing more concisely explains why Gnome towered over the competing small presses of the time than Greenberg’s uncanny ability pull an endless series of rabbits out of his empty top hat. He was the one who emerged from the failed New Collectors Group with the rights to The Carnelian Cube by de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, which became the first Gnome title. He cared nothing for nonfiction but jumped at the chance to put cheap boards on a 75¢ magazine called The Complete Book of Outer Space, and saw it sell fast at $2.50. He never reprinted someone else’s hardcover until he nabbed the opportunity to be the first to publish Arthur C. Clarke in hardcover in the U.S. He saw that even when the other presses failed with elderly books of fantasy, putting all the Conan stories into hardcovers would be like an annuity. Grabbing a prestigious title that had been promised for years for pennies on the dollar was exactly the sort of coup that kept Gnome in business years after the other small presses crumbled.

Those unbound copies came complete with a cover illustration by Prime regular L. Robert Tschirky, adapted for reuse by Gnome regular Ric Binkley. The pages were bound into gorgeous mottled green boards simulating the ocean depths covering an ancient city embossed in silver ink. Greenberg slapped a $5.00 price on it, making it the most expensive title Gnome would ever release. One hopes that Greenberg, for a change, made a ton of money on it. Yet CHALKER makes readers doubt that:

Greenberg and Eshbach say 5000 [copies were printed], but Oswald Twain [the surviving partner at Prime Press], who kept meticulous records, said he only sent 3000 sets of signatures, and no one has reported a second state of this book…

But a second state does exist, an otherwise identical edition with the same dust jacket but bound in gray cloth with the illustration printed in red. By all logic, the nicer binding has to be the original. The cheaper, plainer one must have appeared later on. One possible clue exists. Lost Continents continues to appear in the list of titles on back panels through 1958. It then disappears for the next dozen or so titles until it reappears on the totally redesigned listing for Gnome’s last title, The Philosophical Corps, in 1962. It can also be found on a 1961 Gnome catalog, which sold its piles of warehoused books at bargain prices. Many Gnome titles appeared in gray cloth with red lettering during its last few years. Since keeping an earlier second binding out of many listings of available titles make no sense even for Gnome, the odds are that sufficient unbound copies lurked that a new binding could be released when Greenberg was cleaning house. The logical conclusion is that the bound copies sold out but those were only a fraction of the total printing. Whether that total was 3000 or 5000 is impossible to determine.

Several bibliographic puzzles also arise. Other Worlds published nine articles corresponding to the first nine chapters of Lost Continents. However, the book continues on for two more chapters. Presumably Palmer would have been happy to print those last two, but the magazine stopped publication for two years at that point. Whether those two chapters saw earlier publication is oddly hard to ascertain.

De Camp: An L. Sprague de Camp Bibliography, compiled by Charlotte Laughlin and Daniel J H Levack, provides some clues; even so pinning down Chapter X is impossible. De Camp’s “Preface” to Lost Continents says that “Parts of this book have appeared as articles in Astounding Science Fiction, Galaxy Science Fiction, Natural History Magazine, Other Worlds Science Stories, and the Toronto Star.” Those other titles can be found in Laughlin and Levack, but none are specifically tied to the subsequent book. An article titled “Lost Continents,” a general treatment of the Atlantis theme, was published in the May 1946 Natural History Magazine and reprinted by the Toronto Star. “Lands of Yesterday” in the November 1950 Galaxy Science Fiction concentrates more on ancient land masses. “The Great Floods,” in the October 1950 Astounding Science Fiction touches peripherally on Atlantis. De Camp’s article “The Mayan Elephants” in the June 1950 Astounding is another treatment of Chapter V. None of them appear related to the book chapter, which extends the discussion of authorship from Chapter IX.

The bibliography does say forthrightly that “The Lost Continents of Fiction,” somewhat belatedly published in the August 1954 Science Fiction Quarterly, was rewritten as Chapter XI, although the two versions differ so much that both need to be read for the full treatment. De Camp’s preface was obviously new and written specifically for Gnome but he couldn’t know about Science Fiction Quarterly: the article hadn’t been printed when the book landed in stores.

The mere title Lost Continents is itself an ample source of bibliographic confusion. It riffs on the title of a rousing tale about the lost world of Atlantis serialized in Pearson’s Magazine, July through December 1899, and written by C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne. He was hugely popular in the Victorian world of sensational fiction and an expanded version of The Lost Continent: The Story of Atlantis quickly saw hardcover publication in both the U.S. and Britain. Mary Gnaedinger, editor of the floundering Famous Fantastic Mysteries, reprinted it as a “complete novel” in the December 1944 issue. De Camp surely knew of the both the book, which he called “one of the best Atlantis novels,” and its recent incarnation. Not only are the titles confusable but Hyne’s has a connection because de Camp contributed an introduction to a 1974 edition when it was printed by … Oswald Train’s successor company to Prime Press. Look up either one quickly and you might be fooled into citing the wrong book.

More laughably, newspaper searches for contemporary reviews of the Gnome title find many more hits for yet another The Lost Continent, a 1951 movie ripoff of Conan Doyle that played regularly on late-night television throughout 1954. Extend the search out a year and more stumbles occur when a 1954 Italian Atlantis “documentary,” Continente perduto, was released in the U.S. in 1955 also as The Lost Continent. De Camp got far better reviews than either but lost the battle for newspaper mentions.

Kirkus Reviews gave the expected publication date as April 15, 1954.

Reviews

Groff Conklin, Galaxy Magazine, September 1954

A monument of scholarship, the book is at the same time thoroughly readable.

Unsigned, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 18, 1954

[A]mounts to a tour de force through every branch of science and pseudo-science.

Contents and Original Publication

• “Preface” (original to this volume).

• “The Story of Atlantis” (Other Worlds, October 1952).

• “The Resurgence of Atlantis” (Other Worlds, November 1952).

• “The Land of the Lemurs” (Other Worlds, December 1952).

• “The Hunting of the Cognate” (Other Worlds, January 1953).

• “The Mayan Mysteries” (Other Worlds, February 1953).

• “Welsh and Other Indians” (Other Worlds, March 1953).

• “The Creeping Continents” (Other Worlds, May 1953).

• “The Silvery Kingdom” (Other Worlds, June 1953).

• “The Author of Atlantis” (Other Worlds, July 1953).

• “The Land of Heart’s Desire” (original to this volume).

• “Evening Isles Fantastical” (rewritten version of “The Lost Continents of Fiction,” Science Fiction Quarterly, August 1954.)

Bibliographic Information

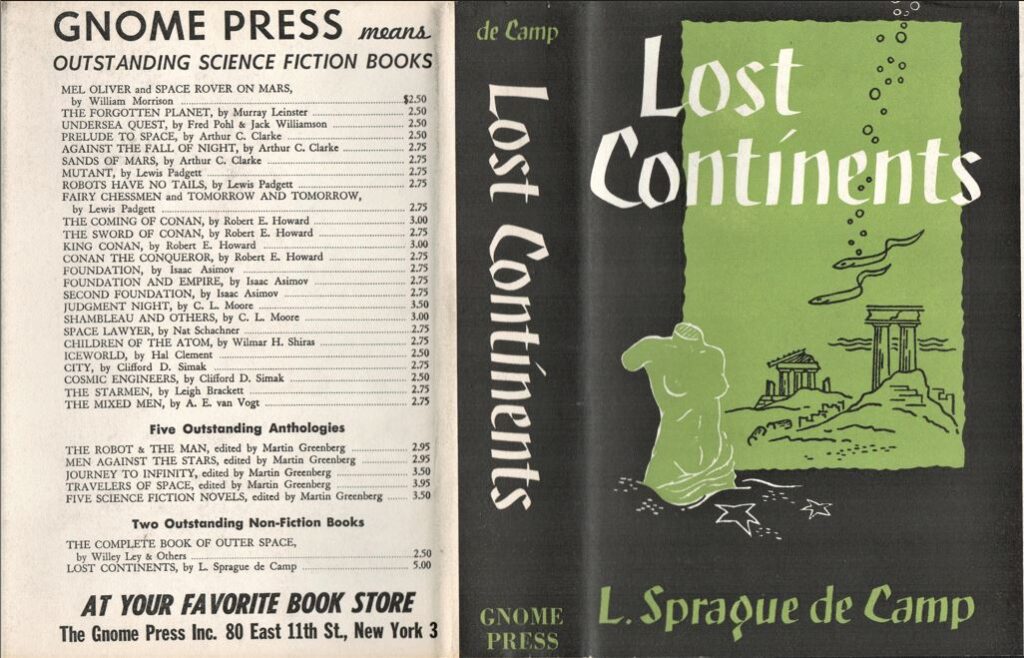

Lost Continents, by L. Sprague de Camp, 1954, copyright registration 25Mar54, Library of Congress catalog card number 54-7253, title #40, back panel #28, 362 pages, $5.00. Either 3000 or 5000 copies originally printed by Prime Press, some bound 1954, second binding 1961?. Hardback. Jacket design by L. Robert Tschirky and Ric Binkley. “First Edition” on copyright page. Printed in the U.S.A. by H. Wolff. Title page adds “The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature.” 17 illustrations and maps. Back panel: 32 books. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

Variants, in order of priority

1) Mottled green cloth boards with silver spine lettering and an embossed silver drawing of underwater ruins on the front boards copied from the dust jacket.

2) Gray cloth boards with red spine lettering and a red drawing of underwater ruins on the front boards copied from the dust jacket.

Images