Comments

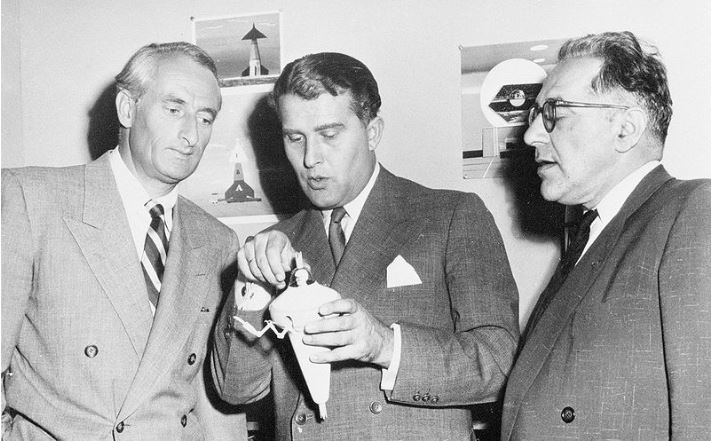

Starting in the late 1940s, a group of enthusiasts, “space-happy” in Robert Heinlein’s term, engaged in an open campaign outside the pages of science fiction magazines to convince the U.S. public that exploring space with rockets was the single most important thing mankind could do in the 1950s. Heinlein’s 1950 movie, Destination Moon, was the first major public example. A series of high-profile special issues of Collier’s magazine, then a striving rival to Life and Look, ran under the collective title of “Man Will Conquer Space Soon!” The first issue, March 1952, with art by Chesley Bonestell and others, featured articles by Willy Ley, Dr. Wernher von Braun, and Dr. Hans Haber, with more articles in October, all collected into an expanded version under the title Conquest of the Moon, which was published as an oversized hardback in 1953 by the prestigious Viking Press. The articles were drawn from lectures given at The First Symposium on Space Flight, held symbolically on Columbus Day, October 12, 1951, at the Hayden Planetarium in New York City.

Call them the Usual Suspects. Before they got to the Moon, they conquered every form of media, culminating with the biggest prize of all. The 1954-55 television season saw the launch of Disneyland, a program explicitly designed to propagandize for Disney’s theme park of the same name. It ran on ABC, and the network also helped bankroll the park’s development. Each episode was tied in to one of the park’s section, like Frontierland or Adventureland. Tomorrowland was a problem. Not until the 20th and last episode of the first season, airing March 9, 1955 and titled “Man in Space,” did Disney present a Tomorrowland episode. It was replete with a cartoon history of rockets and interviews with… Ley, Haber, and von Braun. Forty million people watched and the cartoon was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Short.

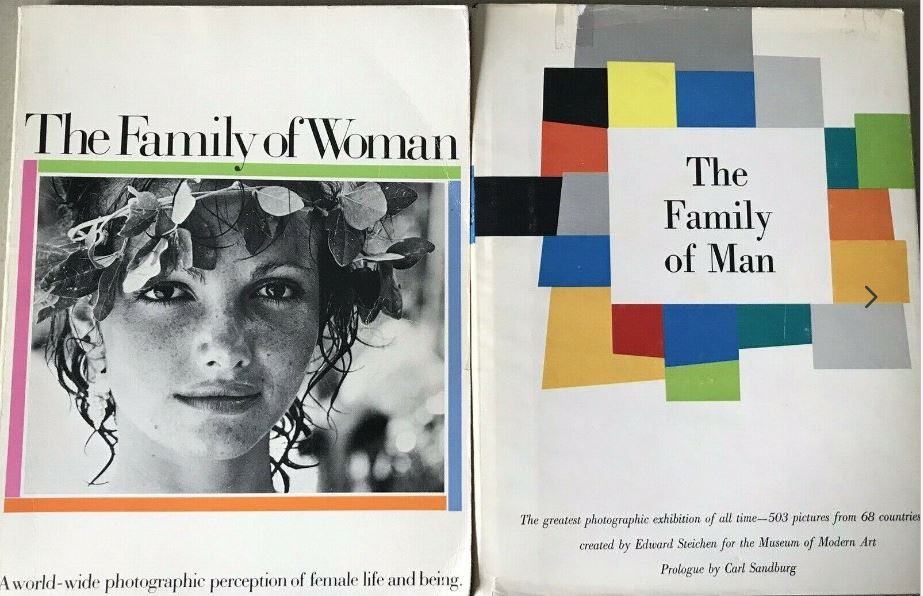

In the meantime, Jerry Mason (1913-1991), editor of Argosy magazine (and of two issues of the pulp Adventure, following Ejler Jakobsson, who would later pop up as editor of Galaxy Science Fiction: the magazine world was a small village inside New York City), had founded Maco Magazine Corporation in 1953. Rather than issuing titles on a regular monthly basis, Maco put out single-topic publications in a small magazine (or perhaps large digest) format, which allowed them to be heavily illustrated with pictures and drawings at a lower cost. Mason’s greatest coup in the four years he headed Maco was being selected to publish a one-dollar magazine edition of The Family of Man, subtitled “The greatest photographic exhibition of all time – 503 pictures from 68 countries – created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art,” with a Prologue by Carl Sandburg, naturally followed up by The Family of Women.

Surrounding that peak were the bread-and-butter titles like The Complete Book of Gardening and Lawn Care, The Complete Book of Cats, The Complete Book of Fishing Tackle, The Complete Book of Horses, The Complete Book of House Plants, and Jim Beard’s Complete Cookbook for Entertaining, essentially a compendia of 1950s obsessions and stereotypes, especially when his Marilyn Monroe Pin-ups is included. Her body funded Mason’s publishing empire just as it did for Hugh Hefner’s contemporary Playboy magazine.

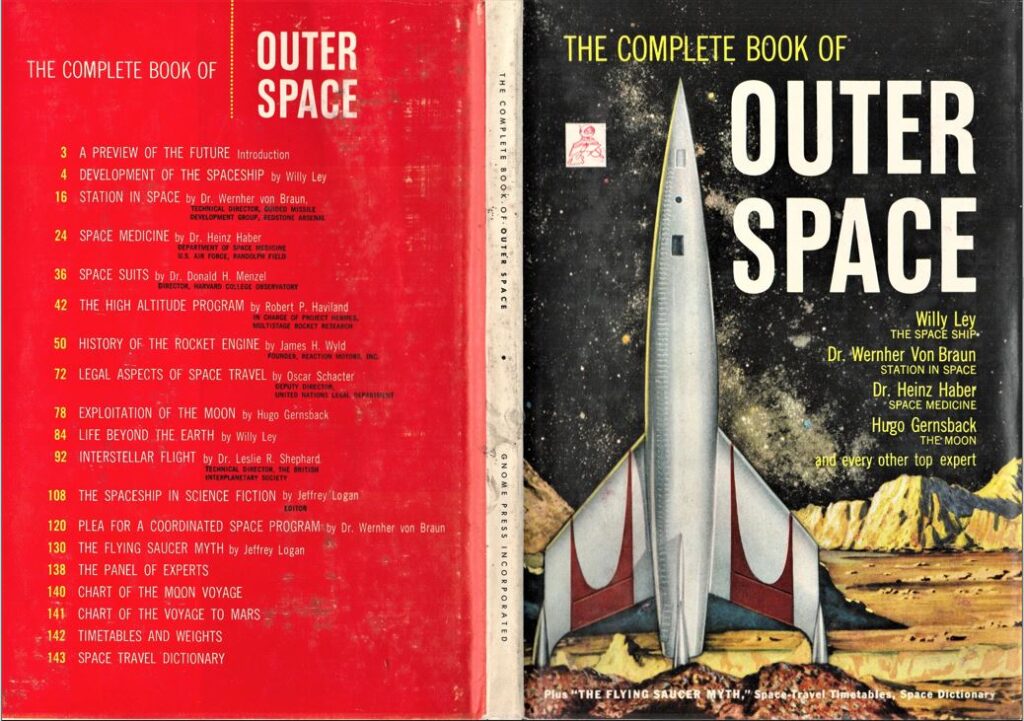

Though it’s hard to believe that the RoI was as great, Mason exploited the Usual Suspects for The Complete Book of Outer Space, reprinting the series of lectures they had done for the Second Symposium on Space Flight at Hayden Planetarium, October 13, 1952. To bulk out the issue, a few other presumably sellable names like Dr. Leslie R. Shephard, Technical Director of the British Interplanetary Society, Dr. Donald H. Menzel, Director of the Harvard College Observatory, and Hugo Gernsback himself were added.

Gernsback, the self-proclaimed Father of Science Fiction, was only 27 years removed from launching Amazing Stories, the first true pulp sf mag. In 1953 he tried another new magazine, Science-Fiction Plus, subtitled “preview of the future.” The field had changed almost beyond recognition since the 1920s, a fact he abhorred. He said in his first issue that he wanted to bring back his ideal of the “truly, scientific, prophetic Science-Fiction with the full accent on SCIENCE. … [not] the fairy-tale brand, the weird or fantastic type of what mistakenly masquerades under the name of Science-Fiction today.” [typography as in original] Science-Fiction Plus was born and died in 1953, probably because, as in Amazing Stories, Gernsback printed articles on science, including the ones by Shepherd and Menzel, and fiction that closely approximated articles. However poor the fiction, the articles were cutting-edge science for a 1953 publication. Gernsback gets another credit in Complete “for much of the artwork” that surrounded the pictures of real-life rockets and missiles provided by the U.S. Department of Defense.

No information is available on editor Jeffrey Logan, except that he is also credited as editor of Maco’s 1954 The Complete Book of Small Boats. Logan contributed the only signed new content: “The Spaceship in Science Fiction,” replete with wonderful images from old magazine covers, and “The Flying Saucer Myth,” mocking it with a blurry photo of a featureless white ball that could have been anything. His role in the unsigned pages that fill out the back of the book is not clear. The copyright registration reads: “The Complete Book of Outer Space [by] Willy Ley [and others]. Managing editor, George H. Levy.” [typography as in original] Levy is also listed as the “appl[ication] author” for Marilyn Monroe pin-ups [sic]. Why he was credited with these two and not any of the many other Maco issues is also not clear.

Chesley Bonestell’s drawings lose 99% of their punch in black and white but the hundreds of other photos made Complete superior in its overall coverage to its far more expensive contemporary Conquest of the Moon. It must have sold well, because Mason released a second edition (with a bare-bones cover) in 1957, although that one is almost forgotten today. The mention of “The Flying Saucer Myth” was removed from the cover, illuminating how quickly and thoroughly the fad had died out.

Gnome Notes

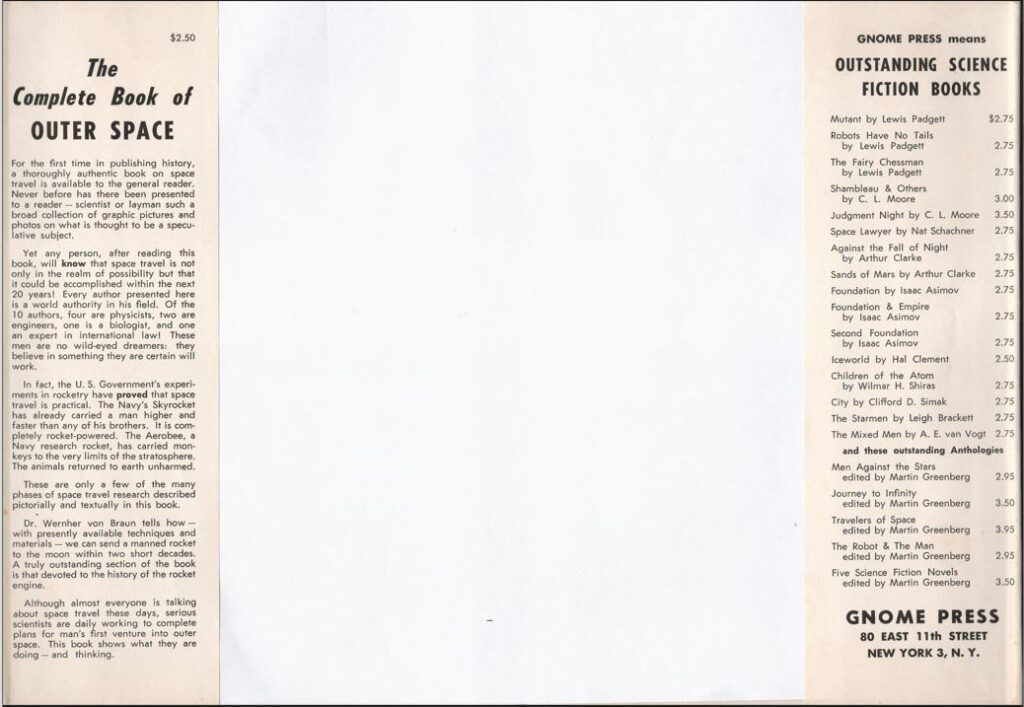

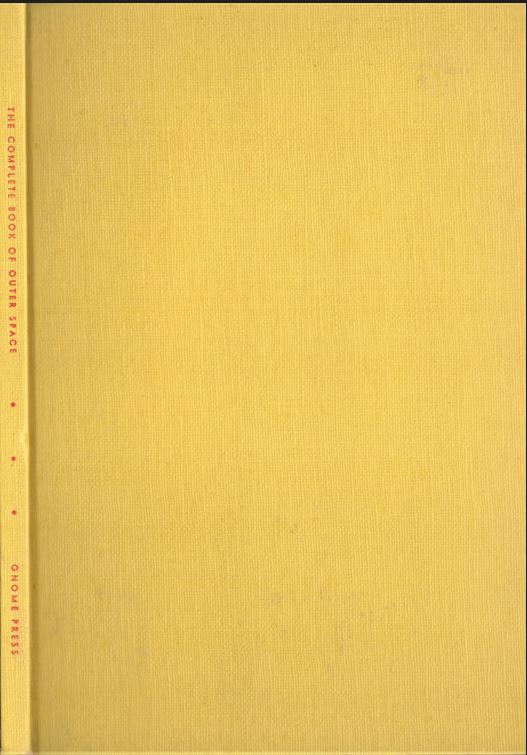

Marty Greenberg saw a niche to exploit. Libraries were a prime market for him, now that science fiction appeared in hardcovers and had gained a modicum of respectability; many of his Young Adult titles were aimed almost exclusively at a library market. Libraries needed hardbacks for their sturdiness. Why not bind the magazine and sell a hardcover edition to libraries with the Gnome imprint? He had an in: Logan had dipped into his Travelers of Space anthology and reprinted Willy Ley’s introduction to that volume.

Greenberg grabbed 3000 copies, put them in the cheapest yellow boards he could find, and copied the magazine’s cover, merely swapping out the Maco logo for Gnome’s own and removing the blue overlay. The result is the largest Gnome release, a shelf-busting 6.3 × 9.7”. He didn’t change a word inside, which doesn’t mention Gnome anywhere except for the Travelers of Space credit that was in the original. The credits for the inside front and back covers are retained, even though the pictures themselves were not. In a concession to his presumed audience he removed all the Conan titles from the list of Gnome’s “Outstanding Science Fiction Books” on the rear flap. There would be no fantasy in the Space Age.

The status and name recognition of Willy Ley in the early 1950s can be judged by the Chicago Tribune mention below and by future Gnome back covers listing Willy Ley as the author of this title. The actual editor’s name is never mentioned.

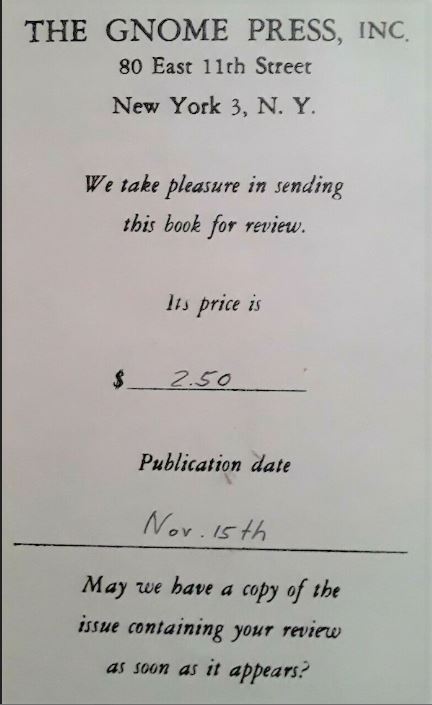

A review slip sent out with a copy gives November 15 as Gnome’s publication date.

The first newspaper mention of this book I can find is in the Windsor [ON] Star, on December 19, 1953. Many of the Gnome books were published simultaneously in Canada by various houses. Complete is credited simply to Nelson. Thomas Nelson & Sons (Canada) Ltd. is listed in the 1952-1953 Literary Market Place as representing The Gnome Press, Inc. Sedgwick & Jackson, which published a number of Gnome books, was the UK publisher. (see The American Paperbacks and The Foreign Editions)

Maco Notes

In a Gnome-like move, Maco misspelled Chesley Bonestell’s name in the credits as Chesley Bonnestell.

Hugo Gernsback is thanked for permission to reprint his article, but no earlier printing of that title or description has ever turned up.

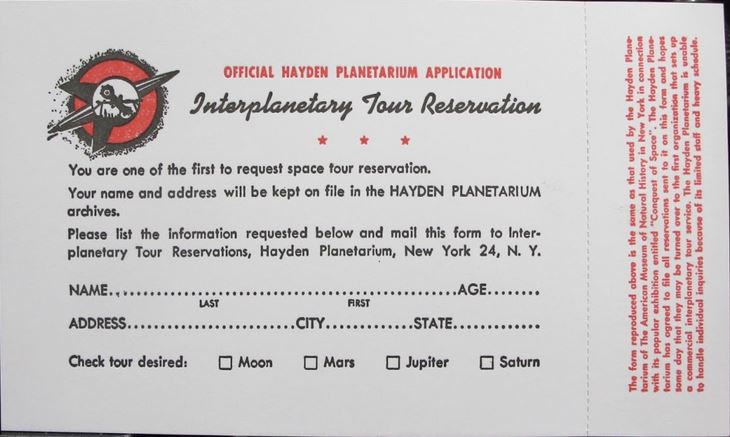

Several of the articles have titles that differ slightly from the Contents page. All titles below are from the actual headings. One of greatest variations is that the article listed in the Contents as “Timetables and Weights” is headed “SPACE charts and tables” on the inside. This material was also taken from the Hayden Planetarium. To promote a 1950 show on the “predicted age of interplanetary travel” based on Bonestell’s “Conquest of Space” art, the Hayden announced it would accept reservations for a future Interplanetary Tour, promising to keep them on file forever.

The stunt succeeded all too well. It generated 10,000 responses in the first four weeks, many of them accompanying the reservation with letters and pictures of why they wanted to go to space and what they wanted to see. Seemingly every newspaper in America picked up on the promotion, reprinting the charts and reservation form, and asking for their own responses. The stunt worked so well that the Hayden repeated in 1952. They kept their promise to keep everything on file. In 2011, as part of a show called “Beyond Planet Earth: The Future of Space Exploration,” the American Museum of Natural History, home to the Hayden, put many of the letters, mostly from kids, up on display. The most complete article on this early Space Age fever fad is Interplanetary Tour on my FlyingCarsAndFoodPills site.

Reviews

Unsigned, Austin Daily Texan, March 14, 1954

Every science fiction enthusiast feels a glow of self-satisfaction whenever a book like “The Complete Book of Outer Space” appears – a book which goes about the business of explaining the business of space travel in a calm, sane, manner that admits of not wild-eyed fantasy or wishful thinking, but takes the eventual conquest of space as matter-of-course.

Unsigned, Chicago Tribune, January 3, 1954

Any list of book titles that stops the reader in his tracks ought to include the “Complete Book of Outer Space,” by Willy Ley and others, published – can you believe it? – by the Gnome Press.

Contents and original publication

• “[untitled preface]” Kenneth MacLeish (original to this volume).

• “Introduction,” (original to this volume; no author credited).

• “Development of the Space Ship,” Willy Ley (Hayden Planetarium lecture).

• “Station in Space,” Dr. Wernher von Braun (Journal of the American Rocket Society, September 1945).

• “Space Medicine,” Dr. Heinz Haber (Hayden Planetarium lecture).

• “Space Suits,” Dr. Donald H. Menzel (Science-Fiction Plus, May 1953, as “Future Space Suits”).

• “High Altitude Program,” Robert P. Haviland (Hayden Planetarium lecture).

• “History of the Rocket Engine,” James H. Wyld (Journal of the American Rocket Society, June 1947, as “The Liquid-Propellant Rocket Motor – Past, Present, and Future”).v• “Legal Aspects of Space Travel,” Oscar Schacter (Hayden Planetarium lecture).

• “Exploitation of the Moon,” Hugo Gernsback (reprint from unknown source).

• “Life Beyond the Earth,” Willy Ley (Travelers of Space, edited by Martin Greenberg [New York: Gnome Press, 1951], as “Introduction: Other Life Than Ours”).

• “Interstellar Flight,” Leslie R. Shepherd (Science-Fiction Plus, April 1953).

• “The Spaceship in Science Fiction,” Jeffrey Logan (original to this volume).

• “A Plea for a Coordinated Space Program,” Dr. Wernher von Braun (Hayden Planetarium lecture).

• “The Flying Saucer Myth,” Jeffrey Logan (original to this volume).

• “The Panel of Experts,” (original to this volume; no author credited).

• “Chart of the Moon Voyage,” (original to this volume; no author credited).

• “Chart of the Mars Voyage,” (original to this volume; no author credited).

• “Space Charts and Tables,” (adapted from Hayden Planetarium releases).

• “Space Travel Dictionary,” (original to this volume; no author credited).

Bibliographic Information

The Complete Book of Outer Space, Edited by Jeffrey Logan, 1953, copyright registration 20Oct53, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number not given [retroactively 55-2168], title #35, back panel #25, 144 pages, $2.50. 3000 copies printed. Hardback, yellow boards, spine lettered in red. Physically larger than all other Gnome Press titles at 6.3 × 9.7”. Jacket unsigned [by Chesley Bonestell]. No edition or printer designated. Copyright Maco Magazine Corporation. Back panel: table of contents.

Variants

None known.

True first edition

Maco Magazine Corp., New York, 1953

Images