Gnome wasn’t the first small press to emerge in the 1940s after World War II; indeed it was very near the last. Gnome’s origins lie in an earlier attempt, the almost completely forgotten New Collector’s Group (NCG).

Paul Dennis O’Connor lived the high life in a big Central Park West apartment he shared with his wife and father-in-law, where he regularly entertained a selection of bohemian artists, like the surrealistic illustrator Mahlon Blaine, Weird Tales gruemeister Boris Dolgov, and supreme fantasist Hannes Bok. Like any great con man he talked a good game. Bok was a huge fan of fantasy writer A. Merritt, also mostly forgotten today but a giant name in the 1940s. At one of O’Connor’s dinner parties, Bok brought up the idea of finishing and, more personally satisfying, illustrating two pieces of work Merritt left behind after his 1943 death. He and two members of the Futurians fan club, Donald A. Wollheim and John Michel, planned to start a company to publish the works. O’Connor swept in ahead of them, optioned the rights, cut out Wollheim and Michel, and somehow got the impoverished Bok to borrow money to form what became the NCG.

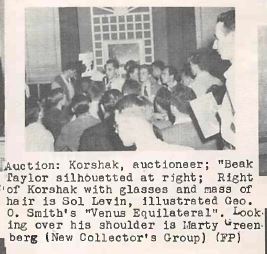

Martin Greenberg met up with Bok and O’Connor on May 4, 1947, in Newark at a meeting of the Eastern Science Fiction Association, another fan club. He was bubbling over with ideas about starting a small press and O’Connor, with his eye always out for a sucker, talked him into investing in NCG, which had released the two Bok/Merritt collaborations but had nothing else ready to go, although O’Connor kept announcing titles that would never be published. As always, people wanted to get in on the ground floor of something that looked to be big. Fantasy Review, a British fanzine, reported in mid-1947 that speculators had bought up the remainder of the 1000-copy Merrit first printings and that the books were changing hands at $10.00 each, a stupendous price for the period.

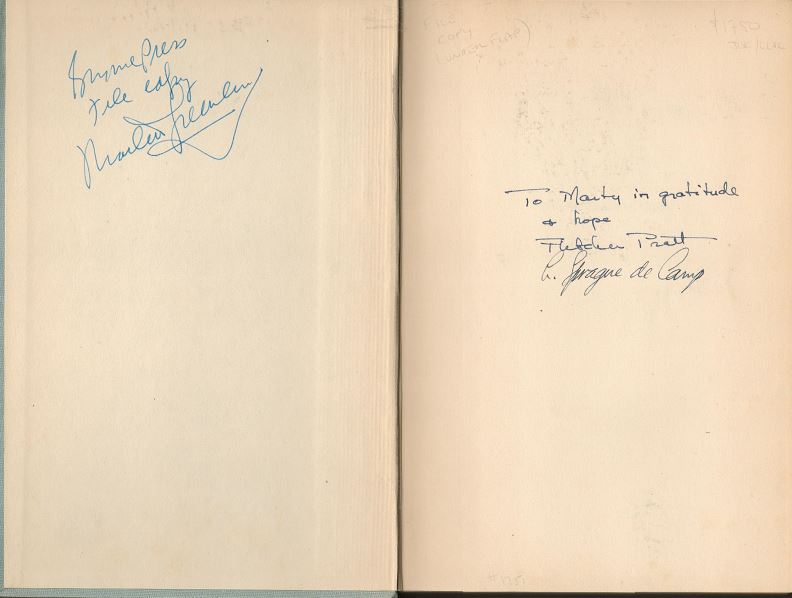

Greenberg’s association quickly paid off. The August 1948 Astounding Science Fiction ran an ad headlined “THE NEW COLLECTOR’S FANTASY BOOK CLUB/ANNOUNCES ITS THIRD SELECTION”. Why it billed itself as a book club instead of a press in unclear, but the ad promised the appearance of The Carnelian Cube by Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp, an original humorous fantasy by two of the biggest names of the 1940s, an obvious and impressive coup for a small press. The address for checks was Greenberg’s, who apparently had negotiated the rights.

Good thing, because by that time O’Connor had skipped town in the literal dead of night. Later revelations showed that he was actually a penniless crook and con man named Robert Young, who despite being gay married his wife for her family’s money. As soon as her father died, he cleaned out her bank account and left her behind. As he did with Bok. “O’Connor” took all of NCG’s funds with him, so that Bok never got a cent out of his investment and work. Worse, he stole a portfolio of Bok’s works and posed as his agent to sell Bok’s illustrations and pocket all the money. He actually put out a couple of additional titles from the safety of Denver but then disappeared until arrested for swindling in 1968 while running the ironically named New Collector’s Gallery. Bok, in the meantime, was reduced to abject poverty.

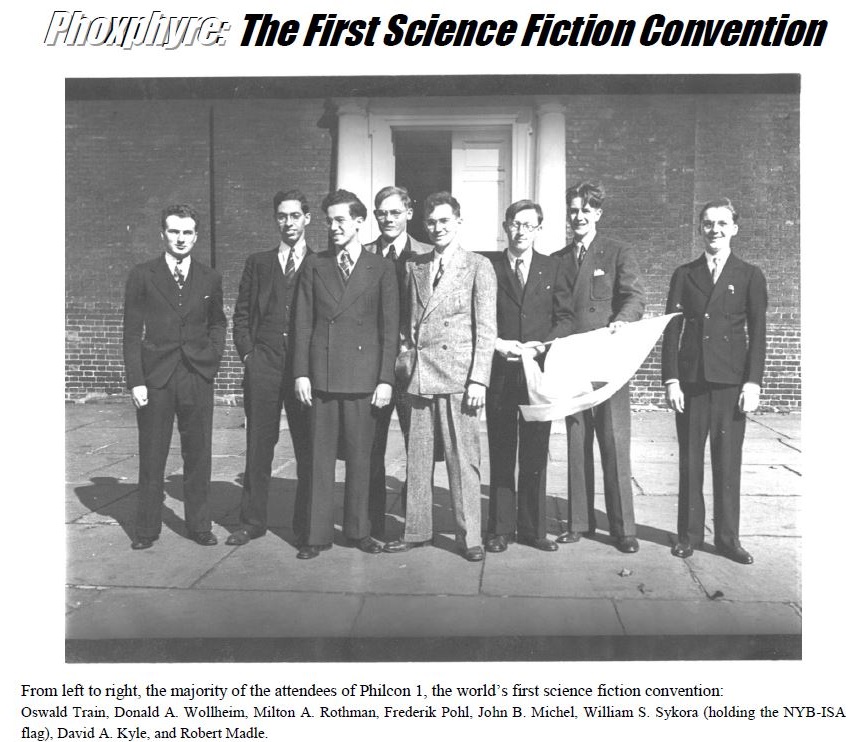

Greenberg had no experience in publishing, especially with regards to the printing the book and getting it out the door function, far more important for a small press in 1948 than any other aspect of the job. He turned to David A. Kyle, who essentially grew up in fandom, reading the pulps from his early teens, and turning into a letter hack, fanzine publisher, founder of fan groups, and all-around friend of everybody in New York fandom, somewhat like being a music junkie in 1967 San Francisco. He was an attendee at the first science fiction convention, in 1936, and at the first “Worldcon,” the annual overarching main convention of the year, in 1939. Like Greenberg, his fan days had been interrupted by the war and he slowly gravitated back to the New York fan scene afterward. How the two met is evidence of the importance of New York to the field.

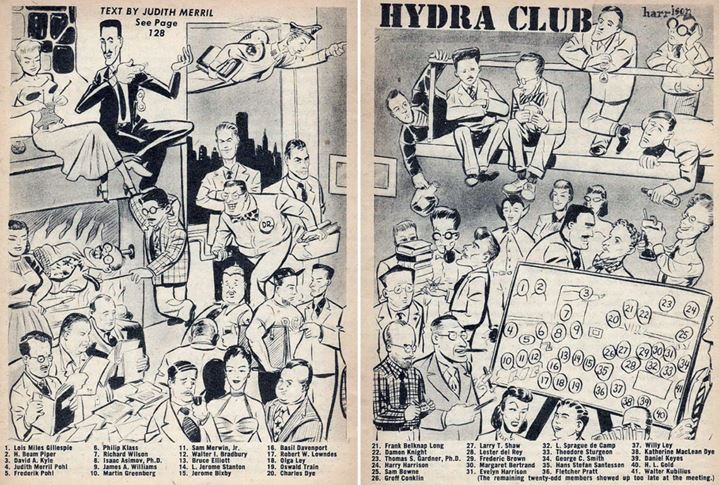

Kyle, who by the end of his life had attended more worldcons than anybody else, took the train to the 1947 Worldcon in Philadelphia accompanied by Frederik Pohl, not yet a giant in the field, but a veteran writer and editor of magazines whose contents pages were filled with Futurians. Today’s Worldcons are huge international affairs attracting thousands: only about 200 people attended the 1947 “Philcon,” but seemingly half of them were professionals, making the weekend a giant in-group party. That left such a “delicious aftertaste,” as Pohl would later put it, that he and a few others plotted to make the party permanent. Nine people gathered in his apartment a few weeks later and formed The Hydra Club on October 25, 1947, after the nine-headed beast of mythology. The only requirement for membership was professionalism. Even Harry Harrison, another later giant, was barred from joining originally because he was still only a comic book artist. The first nine were Pohl, Kyle, Lester del Rey, Judith Merril, Robert W. Lowndes, Philip Klass (William Tenn), Jack Gillespie, David Reiner, and Martin Greenberg. By the end of the decade virtually every professional in the New York area was a member, as Harrison’s illustration from the November 1951 Marvel Science Fiction shows. (Kyle and Greenberg are numbers 3 and 10.)

Greenberg and Kyle became friends and found that they shared similar notions about the need for hardback editions of classic f&sf works. After the NCG imploded, Greenberg asked Kyle to become his partner. Kyle knew everything about printing. He had spent his first year after the war working at his family printing business in Monticello, NY, and even acted as managing editor of the town newspaper, also owned by his family. Little as they had in common as personalities, they meshed perfectly as the two sides of a press’s needs. Kyle later wrote, “Hydra brought us closer together to become book publishers. I put up the money (my Air Corps savings) and used my family’s printing shop while he supplied the contacts and the salesmanship. Hydra members gave us the necessary encouragement. We agreed that he should draw a very modest Gnome salary and that I should work for free because he had a family and I didn’t.” Amazingly, this seemingly inequitable arrangement worked, mostly because Kyle would earn money from an endless stream of outside jobs.

The Carnelian Cube naturally became the first book from the Gnome Press imprint.

Kyle printed it on his family’s press, not one really set up for book work, and nursed it through an interrupted printing. Kyle illustrated the cover and created a logo for the press depicting a gnome sitting on a toadstool and reading a book. The copyright registration was issued on November 1, 1948. The fledgling publishers must have been astonished to see a review in the august New York Times Book Review the next month, even if it wasn’t as positive as they would have liked. “The jacket copy describes this book as a ‘humorous fantasy.’ It is a fantasy in a heavy-handed sort of way, but as for the humor, the less said the better.” Running the review posed a conundrum for the Times editors. As a genre book, it did not deserve a slot of its own, but no f&sf column existed. They punted and shoved the title into the “Criminals at Large” mystery review column. The onrush of f&sf titles stormed the Times’ defenses. By 1950, it created an occasional f&sf review column under an ever-changing title, of which “In the Realm of the Spacemen” is typical. Gnome and the other small presses thus achieved almost instant respectability.

That Gnome started with a fantasy title might surprise today’s readers, considering that Gnome would soon become so totally associated with John W. Campbell’s Astounding that it often seemed to be its official reprint house. Nevertheless, the Campbell connection looms large. De Camp and Pratt were regularly published in Campbell’s companion fantasy magazine Unknown, and Greenberg thoroughly plundered those issues as a matter of course. That Gnome followed with a second fantasy from an author totally unconnected with Campbell should be the real surprise to those unfamiliar with the publishing world of that era.

Fantasy had far more heft with the literati than science fiction. Mainstream publishers could and did include fantasy titles in their general lines without getting disapproving looks or finding their releases shunted off to the ghettos of genre review columns. Henry Holt, a distinguished mainstream house, published two books of Unknown stories by de Camp and Pratt, The Incomplete Enchanter and The Land of Unreason, in 1940 and 1942 respectively, and earlier in 1948 William Sloane Associates released Pratt’s pseudonymous The Well of the Unicorn to rave reviews.

Since fantasy could be published anywhere, it didn’t require the scaffolding that specialty pulps provided for science fiction. Weird Tales comes closest in modern terms, but now-forgotten titles like The Magic Carpet, Tales of Mystery and Magic, and Oriental Tales also supplied concentrated doses of the RDA of fantasy. Frank Owen wrote for all four (and, lest you pigeonhole him, for Young’s Realistic Stories Magazine), earning him an enviable reputation in the 1930s when his orientalist stories were collected in a series of hardbacks that garnered ecstatic reviews. Out of print in the late 1940s, those much-loved stories undoubtedly appeared to be a way to get another huge name to crow about. Or, at least O’Connor must have thought this way, because a collection cherrypicking the four earlier volumes and adding two new stories was one of the many books announced by the NCG before it folded. (His tastes are indicated by his first two publications after he fled to Denver: two paperback chapbooks of orientalist short stories.)

Greenberg took the collection with him and published it as The Porcelain Magician after the title of one of the new stories. The book is said to be “Copyright 1948 by Frank Owen,” but in fact the actual copyright date was February 20, 1949. No reviews appeared before the one in a July 1949 magazine. (That a collection of orientalist fantasies was reviewed in a magazine called Super Science Stories should give modern readers an inkling of how minuscule f&sf hardback publishing was and how desperate reviewers were to scrape together any titles that might even tangentially belong to it.) Its publication merited a mention in a daily New York Times alongside the announcement of a ten-volume new translation of Goethe and two books by Tennessee Williams.

Frank Owen was no A. Merritt. The collection tanked. Gnome would seldom mention it again, even in lists of available backlist books for sale. A single failure could sink a small press but Gnome teased potential buyers with no fewer than five forthcoming titles on the back panel. Two were fantasy, but three were science fiction and Greenberg quickly realized that’s where the audience was. For the rest of Gnome’s existence, sf dominated, outnumbering fantasy about six to one.

Even so, the third Gnome title was another coup that had to appeal to fantasy enthusiasts. Nelson Bond was Frank Owen squared in sales and recognition. Although his first major story didn’t appear until 1937 when he was 29, his typewriter never stopped for the next decade. Bond published around 200 pieces in the pulps, including most of the sf magazines and some of the big-name mainstream fiction magazines. His first collection was to be an event. Even better, Bond brought with him a fabulous bit of promotion. James Branch Cabell is today barely remembered but in 1949 his name certainly was better known by the general public and especially the literary establishment than anyone in magazine-based genre. His ironic fantasies were bestsellers noted for their raciness: a ludicrous obscenity suit against his novel Jurgen brought him national notoriety. A fellow Virginian, he was friends with Bond and gave him the use of the title The Thirty-first of February for the book, as memorialized in a poem he wrote that was used inside the book and on the back panel. In addition, he provided a blurb that ended, “To my judgment, Mr. Bond has genius.” To ensure that the book was treated as a Very Big Deal, Greenberg borrowed an idea from Prime Press and released a special edition of 112 signed, numbered copies in much nicer boards and contained in a cardboard slipcase.

Such a book could not be ignored. The New York Times did not shunt it off. Their chief reviewer, Orville Prescott, reviewed the book as his lead title on the Books page for Wednesday, July 6, 1949. He gave it faint praise at best, but reviewers in the Berkeley Gazette and San Francisco Examiner thought far more highly of it. Considering that Porcelain received no reviews in any publication indexed in two newspaper databases I consulted, that’s a considerable step up.

Saying that February was the third Gnome book contradicts all previous sources, which put it fifth, but the record is clear. The book was copyrighted five months earlier than the usual choice, Pattern for Conquest, received its first mention in a newspaper six months earlier, and was reviewed in an Autumn 1949 fanzine while Pattern had to wait until March 1950 for a review. I’ve completely revised the standard order by comparing copyright and review dates with the evidence of available books from the back panels. Redoing the order to conform to copyright dates produces a clean set of data that is highly correlated across all four data sets. Moreover, it corrects brain-snapping mistakes like having the third book in a series appear before the second book. (See The Dating Problem and the forthcoming The Back Panels for an exhaustive examination of release order and release dates. All bibliographies and other content on this site use this revised ordering.)

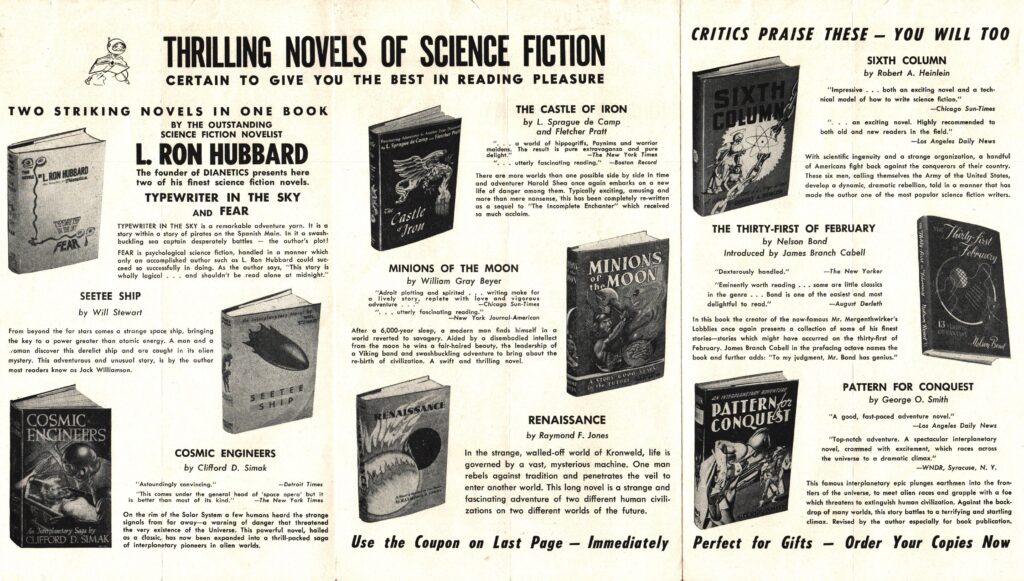

The fourth and fifth books were pure science fiction, drawn directly from the pages of Campbell’s Astounding. George O. Smith and Robert A. Heinlein were perhaps the apotheosis of Campbell-style engineers writing fiction that solved problems with hard common sense and huge steaming ladles of attitude. Pattern was hot off the presses, having been serialized in 1946, an interplanetary adventure during which humanity becomes the most intelligent race in the galaxy. Sixth Column was a more unusual item, having been published in 1941 under the pseudonym of Anson MacDonald when Campbell was saving the Heinlein name for his Future History stories. In it, six Americans rescue the country from its defeat by Asian forces by taking command of atomic energy, gravity, death rays, transmutation and every other device that epitomized pulp sf. These books immediately marked Gnome as the go-to name for modern science fiction, then synonymous with Campbellian science fiction. (“Modern” meant something very different to fans in 1949.) Although they didn’t get as much outside attention as Bond’s book, the fans were primed for more.

The world of small presses in the postwar 1940s can be likened to the world of computer firms in the early PC days. Enthusiasts all over the country bristled with ideas to fill the sudden niche of unfettered opportunity, many of them having the same idea at the same time. They competed to be first, and to be best, and to be the most impressive, and yet felt part of a band compelled to work together to proselytize the amazing new stuff that the rest of the world was just beginning to catch on to.

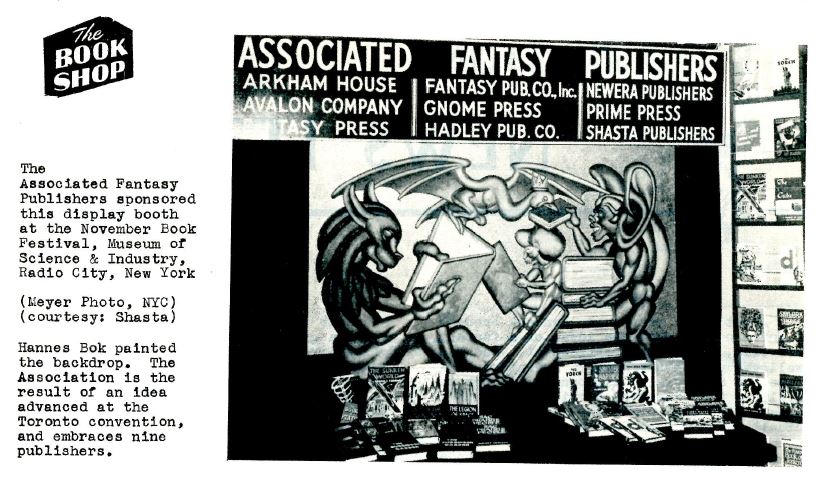

Gnome hadn’t yet put out a single book by the time of the 1948 Worldcon in Toronto, but Greenberg’s partnership in NCG made him an equal player in the formation of The Associated Fantasy Publishers. Individually, the thinking went, the small cash-strapped firms couldn’t afford much publicity, but together they could make a sizable splash. Gnome was one of nine, the others being Arkham House, Avalon Company, Fantasy Press, Fantasy Publishing Co., Inc. (FPCI), Hadley Publishing Company, New Era Publishers, Prime Press, and Shasta Publishers. (The Grandon Company joined later.) Their coming out party took place at the November 1948 Book Festival at the Museum of Science and Industry at Radio City in New York. Hannes Bok painted a six-foot version of one of his fabulous covers that would have stopped all passers-by in their tracks. Antiquarian Bookman, the trade publication of high-end used bookstores, gave the organization attention in a special “science-fantasy” issue – its second in two years.

ESHBACH calls it a pyrrhic victory. The Association drew attention without increasing sales. The attention came from the wrong place. The display alerted the mainstream publishers that they were missing a bet. Just as IBM conquered the PC market over the startups, the small presses would be swamped by mainstream might and money.

Science fiction enthusiasts were innately optimistic in those days; that future either wasn’t seen or seemed too far off to worry about. Besides they were too busy simply devising ways of solving the immediate problem of getting books to readers. The mainstream publishers had squads of salespeople traveling to every bookstore in the country, boasting about their forthcoming wonderful new titles and reminding owners that they could still purchase the evergreen backstock that readers never tired of. Marty Greenberg hired salespeople but would often need to spend valuable hours and days tackling the task himself, a desperate and futile effort. Some bookstores started stocking the small presses regularly, but probably a larger number couldn’t be reached or couldn’t be bothered to research the catalogs and figure out which of these unfamiliar titles with the ridiculous covers they should take a flyer on. Finding a title in a bookstore remained hit and miss for fans outside of the largest cities.

The same solution occurred to multiple people: start a fantasy book club. As mentioned above, O’Connor started billing NCG as a book club, but that made little sense. Unless the offerings cut across several presses it was no more than an in-house ad. Kenneth Kreuger was first to advertise one, in 1946, but he got called up to the Army. He tried again in 1949 with the “Personal Book Association” but that never got traction either. The Fantasy Guild started operations in 1948, with A. E. van Vogt’s The World of Ā as its first selection. That also went out of business quickly, probably because the Reader’s Service Book Club began at about the same time, offering an autographed copy of The World of Ā as its first selection and advertising heavily in Astounding. The Fantasy Fan’s Book Club and the Fantasy Fiction Field Book Club followed in 1950.

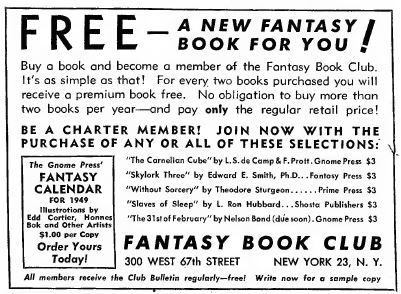

Simon and Schuster rather than a small press had published van Vogt and that may have rankled. Kyle put on another of his many hats and started the Fantasy Book Club (FBC) in late 1948. The first four titles were The Carnelian Cube, naturally; Skylark Three by Edward E. Smith, from Fantasy Press; Without Sorcery by Theodore Sturgeon from Prime Press; and Slaves of Sleep by L. Ron Hubbard from Shasta Publishers. Bob Tucker chronicled the Book Club’s plans in early 1949, mentioning books that wouldn’t be published for many months.

Operating on similar principals as other book clubs, the purchase of any two volumes at the regular price brings you a free premium; first two premiums available to members are THE PORCELAIN MAGICIAN by Frank Owen, and George O. Smith’s PATTERN FOR CONQUEST, each from Gnome Press. Forthcoming selection is THE 31st [sic] OF FEBRUARY, by Nelson Bond. …

Published every other month for members is the club bulletin, detailing all club books and allied fantasy material. The bulletin buys short stories of 2000 words for $25 (slanted fantasy-wise), and is conducting a contest to name the paper. Free copies may be had for the asking.

ESHBACH says that the “FBC continued limping along for several years,” but both the mentions and advertising ceased after early 1949 with this ad in the February 1949 Astounding the last I could find.

The Astounding ad mentions yet another of Gnome’s innovative ideas, a fantasy calendar. Produced hurriedly in 1948 to be available for the start of 1949, each of the twelve months was accompanied by a drawing by Hannes Bok, Edd Cartier, or even ancient great Frank R. Paul, along with a typically fabulous cover by Bok. That’s three major initiatives all before the first book was available in stores. Greenberg always thought big and in Kyle he found a partner who complemented his constant striving.

The back panel for Sixth Column, released in late 1949, reveals how overcaffeinated Gnome’s plans were. All four earlier books are listed under the headline CRITICS PRAISE THESE BEST-SELLING TITLES! No fewer than six books are touted under GNOME PRESS BOOKS FOR SPRING 1950. None of them would be released by then with the L. Ron Hubbard collection waiting until 1951. Another, Minions of Mars, a sequel to William Gray Beyer’s Minions of the Moon, also promised for Spring 1950, never appeared in any form by anyone until 21st century publishers reissued virtually every classic work.

And an eleventh book was teased, without a title or author, but somehow irresistible.

THE BEST BUY OF 1950!

An exciting new type of science fiction anthology

The first in the Adventures in Science Fiction Series, this book taken in its entirety tells a story: the conquest of space. The best works of Asimov, Hubbard, Jameson, Leinster, Padgett, Van [sic] Vogt, etc. $2.95

The dust jacket front must have been printed before the jacket flaps. What else could explain the title and author appearing on the rear flap but not on the all-important rear panel? But who would run a press like that? Put that sentence in a macro. It will need to be used over and over again throughout Gnome’s history.

The mysterious anthology would prove to be Greenberg’s pet project, a series of anthologies each exploring a major theme in science fiction, often arranged so that they unfolded a chronological history of events in the future. Though the flap makes the claim, which would be repeated often, the anthology is probably not the first themed sf anthology. Dell had the previous year issued Invasion from Mars: Interplanetary Stories selected by Orson Welles. Its table of contents was filled with authors who would appear in Gnome titles but did not contain a single Campbell magazine story. Even so, the paperback had a printing of 240,000, close to the total number of books Gnome sold in its entire history, making it far more of a touchstone in f&sf history, one that should be recognized as such.

Nevertheless, Men Against the Stars: An Anthology Arranged as a Future Story of the Conquest of Space, Edited by Martin Greenberg, as the cover read, made a big splash inside the genre. Larger, thicker, and more imposing than any other Gnome title to date, the book was clad in a deep purple half cloth backing over gray boards. In good light, a buyer would discover that the strip of cloth on the front cover was embossed with a rocket ship at the bottom streaming toward embossed stars at the top, a touch of class no doubt added by Kyle, who designed all the early books. (And who is also thanked in Greenberg’s “Foreward” for “assisting with the editing.”)

Greenberg solicited an introduction by rocket enthusiast and popular science writer Willy Ley, whose Rockets and Space Travel was the last word on the subject in 1950. His piece on the history of space rockets capsulated the feelings of space fans, ending with the cogent line, “But it always ends up with the spaceship.” That would be the genre’s star attraction and curse from 1950 to today. The spaceship led readers, watchers, listeners, players, and dreamers to science fiction yet would forever constrict the field within the bounds of its narrow cylinder.

Contemporary readers leapt upon the anthology. The five books in the Adventures in Science Fiction series are considered to be among Gnome’s best sellers, up there in a league with the Big Three: Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein. The first three anthologies would receive true second printings to keep them in stock and advertised on back panels through 1960. No other proprietor of a small press put his name on product, let alone a set of innovative, popular, and critically-acclaimed books. Gnome was already making strides past its competitors with bold, brash statements.

From the inside, 1950 appeared to be the year in which Gnome would take off. To do so, Greenberg reasoned, they needed serious cash. Gnome incorporated itself on January 5, 1950, with Greenberg as President and Kyle as Vice-President. David E. London and Abraham Epstein became secretary and treasurer, though I’m not sure who was which. What happened next is not clear. ESHBACH says that the two newcomers served as money men, putting $10,000 into the business backed by shares of stock. Epstein’s certificate shows that 50 shares were issued to him, same as Kyle’s. CHALKER, however, says that after incorporating Greenberg took out a $10,000 commercial loan. The terms of the loan were ruinous: the interest rate was usurious and the whole could be called in within a year.

Greenberg shared his memories in a 2014 interview with Filmfax Plus magazine and naturally these differ from the other accounts; he was 95 at the time. He identified Dave London as the owner of the Broadway Bookstore and Abe Epstein as a distributor of remaindered books. Epstein was supposed to supply the salespeople that went to bookstores. They did, and they were good at their jobs, but they sold books from everybody so that Gnome became an afterthought for them. Eventually Greenberg had to take over the job. London, he said, was the $10,000 investor but for some reason didn’t want Greenberg to advertise. That rightly frustrated Greenberg who offered to buy him out “after a couple of years.” However, London wanted $20,000 for his stock. He paid it but “that broke me.”

Gnome never truly recovered. From a successful, innovative, even classy business, Gnome slipped into a Sisyphean nightmare that required continual sleight of hand to stay out of bankruptcy, involving ruthless cost cutting, withholding of royalties, sales made without informing authors, and relentless release of product in hopes of creating the cash flow needed to open the doors the next day. That Gnome was able to do this for a decade, twice as long as any of its contemporaries, is proof both of Greenberg’s amorality – or, more politely, his obsession with his company – and his personal charm. An anecdote from Kyle about Asimov captures this quality.

After several years when he had accumulated royalties, he was owed a great deal by Gnome Press. He went to New York with a strict admonition from his then wife Gertrude to collect what Marty Greenberg (Gnome’s treasurer) owed him. She indicated that he had better come back with a payment. Isaac showed up at the Gnome office. Marty confided to him that the latest shipment of books was being held up because of an unpaid bill and that if the bill could be paid the books would be released, the orders would be filled, and cash would flow again so royalties could be paid. Sly Marty could touch the right buttons. Isaac went back to Boston without any royalty payment. He had a difficult time keeping Gertrude from knowing that he had, instead of collecting from Marty, actually lent him some money.

Asimov, unusually for him, said the same thing in fewer words. “Greenberg was the kind of man you’d show up at a convention ready to murder and somehow wind up buying him a drink.” Personality trumped everything in the small world that was science fiction. Only personality – and the lack of good alternatives – can explain why authors and agents kept dealing with Greenberg even after years of his stiffing them. An example comes from Frederik Pohl as Clifford D. Simak’s agent. On February 8, 1950, he wrote Greenberg that “Simak is doing a ten-thousand word insert & amplification on COSMIC ENGINEERS for you. He says he wouldn’t do it for anybody else, but he likes you.” [capital in original]

Pohl’s agency was in the same building as Gnome’s offices. He and Greenberg must have seen each almost daily when they were both in town. Yet his frustrations often boiled over into letters, perhaps because he felt himself able to be more candid when not face-to-face with Greenberg’s glib nature. (Kyle, by contrast, seemed to have been beloved by everyone since the glaciers covered the Gnome offices.)

Science fiction publishers are no better than any other mortals at seeing the future. From the perspective of early 1950, the decade looked asymptotically wonderful. Greenberg had just quit his job to devote full time to Gnome, moving its office from his home at 421 Claremont Parkway in The Bronx to a room on the third floor of 80 East 11th Street in Manhattan.

ESHBACH’s shorthand description of him captures this moment. “Marty was characterized by boundless enthusiasm. It was contagious, uninhibited – and sometimes misdirected. It led him to make commitments impossible to keep. He knew science fiction and fantasy and he had good ideas.” Flush with money, Greenberg launched yet another scheme to make Gnome the center of the f&sf universe, a new magazine. Only a handful of genre magazines existed in early 1950. Astounding was still dominant, Amazing was drowning in a sea of woo, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F&SF) was so new that it hadn’t yet found a voice, and a few old-fashioned pulps survived as dinosaurs who didn’t realize they were extinct. A competitor to Campbell was exactly what the field needed. The recognition of f&sf as a legitimate genre and the rise of a generation of new authors looking for venues seemed to offer a niche as vital and rewarding as the one that the small presses rushed into.

Bob Tucker somehow sucked all the news and rumors of the field into his outpost in remote Bloomington, IL. (Arthur Wilson “Bob” Tucker is an excellent example of the strengths and limitations of the genre at the turn of the decade. The field supported a gloriously active and devoted fanbase but seriously limited the ability of professionals to sell books. Using Wilson Tucker as his book name, he turned out a half dozen mysteries from 1946 through 1951 because that genre adsorbed hardcovers by the hundreds. From 1951 on he wrote only science fiction novels, the field finally accommodating his interests.) The July 1950 issue of his Science Fiction News Letter, “the leading newspaper of the science fiction world,” announced no fewer than three new forthcoming American magazines interspersed with rumors of five others. One of the first three was the revival of the pulp Marvel Science Stories, promised for August. A second was an untitled digest-sized magazine from Horace Gold. The third was from Gnome, also untitled, but providing more details than Gold’s. It would be edited by Hydra co-founder Phil Klass, better known to readers as William Tenn, witty and erudite. Priced at 25¢, it would be a bi-monthly until February 1951 and in pulp format but “parapulp in slant.” The first issue would be ready by September.

None of the three hit their targets. What became Gold’s Galaxy Science Fiction debuted in October and would own the early 1950s almost as thoroughly as Astounding owned the early 1940s. Marvel came out in November and managed five more unimpressive issues before folding. And Gnome’s magazine, whose name was to have been Star Science Fiction, never appeared at all, cancelled before the year was over.

This was truly a pity, because a revised description in the December Science Fiction News Letter leaves us with the tantalizing what if of possibly the most epic, genre-breaking magazine of the entire classic era.

The magazine, according to the would-be editors, was slanted well off the familiar path of s-f periodicals. Primarily, it was aimed at female readers and to capture the women’s audience the first issue was to use only fiction written by the ladies in the field: Shiras, Merril, MacLean, etc. Book was intended to be a 35¢ monthly, digest-size. The covers were to be patterned in the New Yorker style – sophisticated humor. As for instance, a dog in a spacesuit, mournfully eyeing a lamppost.

Insert wailing, gnashing of teeth, tearing of hair, rending of garments. Although F&SF would approximate this role by the end of the decade, the thought of a successful magazine of this description belying virtually every stereotype of the spaceship-obsessed genre of the 1950s should warm the hearts of all literate readers wistful for the field that might have been. Clearly, the ill-advised loan shattered Gnome’s financial position rather than strengthened it.

CHALKER says that the loan was called in “when the first signs of a downturn in sales occurred,” not surprising given the mixed bag that was Gnome’s 1950 selections. A series of titles exactly wrong for the times failed to lure readers or critics: another de Camp and Pratt fantasy, The Castle of Iron; a musty far-future adventure story, Beyer’s Minions of the Moon, dredged out of a non f&sf pulp; and a super-science story from Clifford D. Simak’s salad days, Cosmic Engineers.

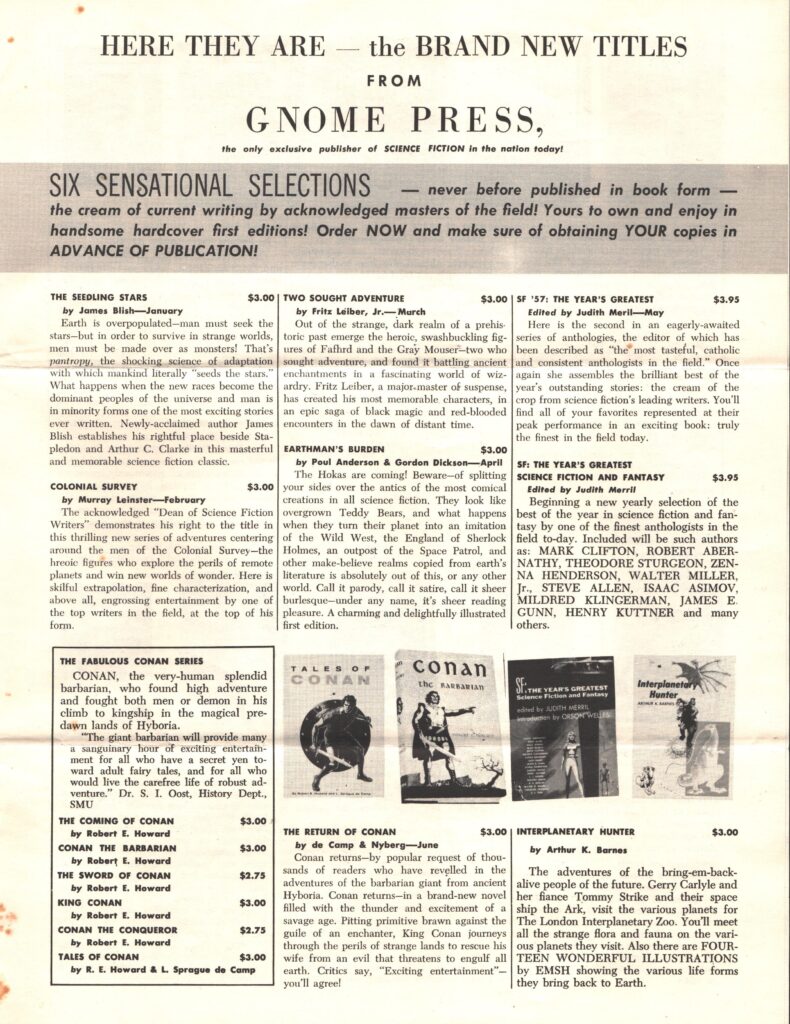

If the money men had only waited. Two books released late enough in the year that they received no attention until 1951 are in hindsight evidence of Gnome’s eminence as the premiere small press, books that would sell endlessly, be made into movies, and become cultural touchstones: Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Conqueror and Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot. Conan blew away all notions that classic fantasy couldn’t sell to modern audiences. The original stories stopped in 1936 with Howard’s early death, but that apparently did nothing but create pent-up enthusiasm for the stories’ re-release. That they had appeared up to a mere fourteen years earlier may make it seem today as if they were too new to consider ancient material, but contemporary readers rightly considered anything that had been published before the war in magazines to be almost as totally inaccessible as Tutankhamen’s treasure before Howard Carter brought that back to light. Another four books followed, reprinting all of Howard’s Conan stories. Not enough. De Camp caught the Conan bug and went through a box of Howard’s unpublished material for work that could be reimagined as Conan stories. Then a Swedish enthusiast, Bjorn Nyberg, wrote a piece of Conan fan fiction that de Camp reworked and smoothed. Later de Camp, Nyberg, and Lin Carter would write even more “official” Conan tales. Gnome begat an industry.

Asimov was a name in 1950 but not the colossus he would later become. I, Robot would help launch him into that stratosphere of Big Name authors. His work went back almost as far as Conan, with his first robot story published in 1939, but he was alive and publishing. His most recent robot story had appeared in the June 1950 Astounding, and Greenberg rushed the process so that he could turn around the book before the end of the year. What’s more, Asimov benefitted from the irony that the book bore a title he didn’t want yet so permanently pinned the robot image onto him that his is usually the first name thought of in connection with them. (His title was the dismal Mind and Iron. Asimov became legitimately furious with Greenberg over his equally dismal record of paying royalties, but the title change alone must have eventually been worth millions to Asimov.)

In a decision incomprehensible today, Asimov’s mainstream publisher, Doubleday, told him they wanted only his new novels and had no interest in reprinting his magazine stories. Another mainstream house, Little, Brown, told him the same thing. Gnome was his safety publisher. So, his other series, the Foundation stories, also landed at Gnome. Foundation (1951), Foundation and Empire (1952), and Second Foundation (1953) were smashes, all three getting reprints allowing them to stay in stock until 1960.

Gnome issued its first catalog in the summer of 1951, undated but advertising books due out in August, September, and November 1951.

(Only Foundation was published in September as promised. Lewis Padgett’s Tomorrow and Tomorrow/The Fairy Chessmen waited until December, Greenberg’s Travelers of Space anthology slopped over into January, and The Sword of Conan didn’t appear until April of 1952. Fans were undoubtedly used to the vagaries of small press publishing but bookstores and libraries would have expected more professionalism.) Readers could order from a sprightly list of seventeen titles (Porcelain was discretely left off, but so was Men, indicating that it had already sold out), with prices ranging from $2.50 to $3.95 postpaid. Pricing mattered greatly. Carnelian and Pattern had been priced at $3.00. So had February, with the slipcased edition at a gaudy $5.00. The proper price point for a genre novel proved to be $2.50. A 50¢ difference seems small, but it’s proportionally the same as a drop from a $30.00 book to a $25.00 book today. Pattern, Sixth, Castle, Minions, Cosmic, and I, Robot all had their prices dropped to $2.50 (another indication that Pattern and Sixth follow February rather than precede it). Conqueror got priced at $2.75 in the middle of this sequence, a show of specialness, but by mid-1951, Greenberg needed to bump all books up by that quarter. The big, fat, 400-page Traveler, with interior color illustrations, needed and deserved its $3.95 pricing, and sales revealed that buyers recognized the distinction.

The 1953 catalog illuminated a company at its peak. Longer and better looking than its 1951 counterpart, fans could buy a stellar lineup, a veritable canon of classic f&sf, including the complete Foundation trilogy, Simak’s award-winning City stories, Arthur C. Clarke’s first American hardback, Sands of Mars, four more Greenberg anthologies, three more Conan books, novels (or collections billed as novels) by A. E. van Vogt, Henry Kuttner, and Hal Clement, and no fewer than three books by women.

Unquestionably, classic f&sf was a boy’s club, but much mental expenditure has gone into the determination of just how much of a boy’s club it was and whether editors and fans discriminated actively or covertly against women. Evidence provided by tables of contents, letters to the editors, and fanzines overwhelmingly agrees that women were welcome. Editors frantically sought find good stories by good writers and bought and promoted them once they had them in hand, no matter whose name was affixed. Fans cheered their favorites on in the same way. The barrier, if there were one, lay in society’s determination that science and engineering were for boys. Few girls got the encouragement to take technical training or go to work in a lab. They were steered to books and magazines that featured subjects considered more appropriate. As a result, the science fiction genre was at least 90% male. Fantasy supported a somewhat higher percentage of women, but it was too small a fraction of the field of f&sf to raise women’s numbers. According to a survey by Eric Leif Davin, women in the Hugo Gernsback and Campbell eras, 1926-1949, provided 63 authors of 283 stories. A sizable number, but my estimate is that these comprise only 3% of all stories, and probably a smaller percentage of wordage since these were more likely to be short stories or novelettes than novellas or serializations.

The hard truth is that there was exactly one A-list author who was a woman, Catherine Louise Moore. She was a star from her first published genre story, “Shambleau,” which appeared in Weird Tales in 1933. (Weird Tales is not included in Davin’s tabulation of sf magazine tables of contents, which skews the numbers downward. Moore had a total of 16 stories there.) Her stories never appeared under her full name, to be sure, but that was because she worked at a bank, which generally were institutions so staid that pulp writers were not considered suitable employees. From the start she was C. L. Moore or, after she married Henry Kuttner, part of the joint pseudonyms Lewis Padgett and Lawrence O’Donnell. Editors made sure the initials fooled only those who ignored all the supplementary material around the fiction. “Miss Moore,” as Gnome referred to her, was always known as a woman.

Second to Moore in recognition and number of sales was Leigh Brackett. Born with that ambiguous first name, she didn’t need pseudonyms. Several dozen of her stories appeared in genre magazines before she married super-science writer Edmond Hamilton in 1946. As with Wilson Tucker, her first books were mysteries, one of which caught the eye of Howard Hawks, who hired the 30-year-old to work on the screenplay for The Big Sleep, along with veteran screenwriter Jules Furthman and Nobel Prize winner William Faulkner, surely the most unlikely trio ever to be credited for a major movie.

At the other end of the spectrum, Wilmar Shiras – also her real name – was an unknown tyro in the field when she submitted “In Hiding” to Astounding in 1948. The poignant story about mutant supergenius children struck a national nerve after the war. If not exactly a star, Shiras was a nova.

Gnome published five books by the three from 1952 to 1954, an off-the-charts number considering that their four major small press rivals published two books by women, and that’s two total over their entire runs in the 1940s and 1950s. Gnome would match that just with books by Andre Norton, using the pseudonym Andrew North, in 1955 and 1956. (Norton masculinized her name because she wrote boy’s books, a field that demanded male names on the covers.) Finally, Gnome published four anthologies by Judith Merril, a genre insider, member of the Hydra Club and briefly married to Frederik Pohl, as well as a writer who made a splash equivalent to Shiras’ with her first f&sf story “That Only a Women,” also in Astounding in 1948. That gave Gnome a near monopoly over the star women in the field. This is somewhat marred by Greenberg’s not picking up on the women who debuted in the 1950s, mostly in F&SF and Galaxy. To be fair, nobody else did either. Merril, who paid close attention to those magazines, had only about a half dozen stories by women in her four anthologies, three by Zenna Henderson, who had no books appear in the 1950s. It’s also true Greenberg didn’t pick up on many of the men. He stayed an acolyte of Campbell until the end.

The rapid growth of Gnome put strains on both Greenberg and Kyle. Greenberg was so much the public face of Gnome that Kyle almost always gets slighted and pushed to the background. In fact, he was Captain Everything, responsible for several peoples’ worth of jobs, a fact that became obvious when he left and the quality of Gnome books plummeted. He did “the editorial writing and editing and acted as production manager and art director.” To help improve his skills he enrolled at Columbia University. Courses there “helped immensely in steering me along the way. Using my artistic talent and training, I designed the original colophon or special identifying design for Gnome Press – a gnome sitting under a toadstool reading a book, inspired by the design used by my father for Merriewold, a mountain residential park. The early books were designed by me and the quality was kept very high. I believe that the little touches which cost a bit more, such as my little symbol embossed in the cover of Asimov’s I, Robot, the chain design for the title page of Heinlein’s Sixth Column, and the split binding and special embossed rocketship on anthologies, made Gnome books distinctive.”

Kyle found ingenious workarounds to the almost minuscule Gnome budgets that created effects that looked far more expensive than they were.

The full color signature or folio in the anthology Travelers of Space was actually done from black-and-white drawings. All color was laid in by a talented printing plant technician who worked with me for the final results. He had done similar work for Lloyd A. Eshbach in the production of some of Lloyd’s Fantasy Press books. I did something similar in color work … for the printing of the dust jacket for Raymond F. Jones’ Renaissance. I made separate drawings or overlays in black for each of four colors. Then, as each color was printed as visualized by me, the final jacket took shape. What the finished product would look like was only in my head – only as the colors went on did the design begin to materialize. Voila! Four colors without the expense of color separation. I did the same thing for Gnome’s L. Ron Hubbard book, Typewriter in the Sky and Fear – I drew separate plates for each color. It was not as complicated as Renaissance and I had a better control over the end result. That jacket is one of my favorites, but some colors in the spine after exposure to years of light have faded badly. I used the same innovative process for the Conan books – the crown for Conan had some intricate color work to highlight the jeweled head piece. These were some of the ways I cut expenses for Gnome publications, for dust jackets with color separation technology were extremely expensive yet absolutely necessary to make a book attractive and saleable. After all, it wasn’t easy even in the 1950s to be able to sell a hard cover book of high quality for only two dollars and fifty cents!

Greenberg cast around at the same time for editorial help. He asked Norton to become a first reader. Norton had been working for the Cleveland Public Library since the Depression forced her to drop out of college in the early 1930s, but severe attacks of vertigo confined her to her bed. In a 1996 interview she said, “In the 1950’s I worked for Gnome Press, reading manuscripts for Martin Greenberg for about three years. This was a time when I was otherwise unable to work, due to continuing attacks of vertigo. Marty would send manuscripts to me, and I would read them in bed. One of them was The Forgotten Planet by Murray Leinster. Greenberg did not send them regularly, since he didn’t have a lot of money. He said that he wanted to bring out books that could be sold as a series to high schools, so I began writing The Solar Queen. [The name of the ship in Plague Ship and Sargasso of Space.] He didn’t want me to write as Andre Norton, since I was working for Gnome Press. He asked me to pick out another name, and Andrew North sounded close, so I chose it.

Late in life memories are useful, but often wrong in the details. Norton’s work for Gnome is unusually hard to pin down. Her obituaries state that she started in 1950 and stayed until 1958. Her comprehensive online tribute site, www.andre-norton.org, is not helpful. Its two main biography pages – written by the same person – manage to disagree with one another, one saying three years, the other eight. Another source says she worked for six years, 1952-1958.

Harlan Ellison’s fanzine, Science Fiction Bulletin, breathlessly announced in 1952 that Norton “has been selected to head up Gnome Press’ new children’s library. They are leading off with several books (all originals) that are supposedly pretty terrif. One is Circus by Lester del Rey which tells of the circus of the future.” Another fanzine referred to her as “editor of the Gnome Press teenage … department.” [ellipses in original] No such book ever appeared from del Rey and Gnome didn’t start its “Gnome Juniors” until 1954. Even then it skipped over its first and only true children’s book, William Morrison’s Mel Oliver and Space Rover on Mars. The Juniors designation was applied to two titles that today would be called YA books, The Forgotten Planet by Murray Leinster and Undersea Quest by Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson. The Juniors were aimed at libraries as a primary market, but quickly got scuttled because Forgotten was wrapped in a dust jacket prominently displaying a giant beetle and the librarians found that inappropriate. Additional YA titles in later years were released without any special designation.

Libraries would remain a major market for Gnome for adult books as well. Patrons started regularly requesting science fiction as a genre and the librarians, if gingerly at first, became more and more receptive as they got deeper into the 1950s. Many small-town newspapers listed new purchases at their libraries, giving an unexpected deep look into buying patterns. At first, f&sf titles are scattered among lists of fiction. In just a few years they earned separate designation similar to mysteries or westerns. Librarians wrote articles on their appeal. Gnome greatly benefitted from targeting libraries; more mentions of Gnome titles can be found in these listings than in reviews. Some libraries bought them by the bunch, five or eight at a time.

The amount of time the busy Kyle devoted to Gnome must have varied greatly. After his Columbia degree, he and his father bought a radio station in upstate Potsdam, NY, which demanded his presence. As Kyle slowly phased himself out of daily operations, leaving entirely in 1954, Greenberg brought in a series of assistants, all of them young and two attending Columbia. Algis Budrys was first, a serial college dropout who left Columbia for a brief stay at Gnome in 1952 before moving over to Galaxy for another brief stay before trying to write full time. His first two stories were published while he was at Gnome. He was another member of the Hydra Club, and Kyle – whose girlfriend at the time was Lois Miles – gives yet another story about what the propinquity of the group begot.

“Lois became a regular at the Hydra Club, and when I became chairman, she became the secretary. Lois had two friends who subsequently became regulars at Hydra, Carol and Edna. Carol became Fred Pohl’s wife after Judy Merril, and Eddie became Mrs. A.J. Budrys.”

Joe Wrzos was a graduate student at Columbia when he followed Budrys from 1953-1954. He moved to New Jersey for a lifetime as an English teacher, although he edited Amazing and Fantastic magazines for a few years in the 1960s. Greenberg’s legendary persuasion somehow lured Larry Shaw, then the editor of Infinity Science Fiction and Science Fiction Adventures, into during copy work for him, whether paid or unpaid is unknown. Earl Terry Kemp (the Kemp whose bibliographic work on Gnome and the other small presses has been consulted innumerable times in the writing of this history) noted later that during his fan days, he had for years “been typesetting Marty’s Gnome Press ephemera. Book lists, advertising copy, newsletters, dustjacket back cover and flap text, all the usual. Larry Shaw wrote the copy and I set it into type. I don’t know what Larry got out of it but I was getting all the Edd Cartier dinosaur bookplates I could handle and an advance copy of each new Gnome Press Book as it was published.” The dating is ambiguous but seems to include 1956. Ruth Landis was Kyle’s girlfriend when she joined Gnome, probably in late 1956 or early 1957. Her stay was brief. She and Kyle married in 1957 and settled in upstate New York.

Greenberg left a single anecdote about his hirelings. “Dave Kyle was no longer with the company and I was alone, and I had a secretary (laughs) and when I was on the road found out that he left at three o’clock.” Whether this person was an actual secretary or one of his Assistant Editors isn’t clear. How much work an assistant or secretary could do at Gnome when the times were slow also isn’t clear, although all 1950s businesses generated piles of paperwork.

I have a letter that Greenberg sent on April 2, 1951, to Forrest Ackerman, a superfan, agent, editor, reviewer, and collector extraordinaire, about an earlier slog. “My salesman for the midwest had to have an operation and has been in the hospital for the past week. As a result I have had to call on our accounts.” Somewhat more surprising is the revelation that Ackerman was working for Gnome. He was getting $2.00 an hour for correcting galley proofs. Greenberg, not surprisingly, writes “Frankly, I don’t have to [sic] much reserve cash” and asks Ackerman to deduct it from “what you owe us.” Apparently, Ackerman, who lived on the west coast and sold books from there, was buying copies of Gnome books in bulk for resale. “You already have Renaissance and Typewriter is being shipped about the 15th of this month with Settee Ship to follow shortly.” [no italics as in original] That sequence conforms to my revised dating over the traditional dating.

Wrzos was a touch more voluble about his experiences. He was the one who suggested to Ric Binkley that a bald woman’s face would work for the cover of Lewis Padgett’s Mutant. One of the perks of the job for a young fan was getting to meet the authors who stopped in at the office, sometimes pleasant, sometimes far less so.

An even more memorable encounter took place a year later, in 1954, when Will F. Jenkins, better known as “Murray Leinster,” stalked into the office one day, quite indignant at Andre Norton, one of Marty’s (unknown to me at the time) upper echelon first readers of preferred manuscripts. When Marty had mailed Jenkins the critiqued Ms. of the as-yet untitled Forgotten Planet, not uncharacteristically, he forgot to remove Norton’s negative written comments from the package. What the usually laid-back, unflappable Jenkins took offense at was Norton’s assault on his writing style. In her notations, she faulted his writing for its “poverty of expression.” If that were so, Will pointed out, why then had he been published successfully for almost half a century? … A good argument, which Marty and I dutifully nodded agreement on.

After Jenkins left the office, though, the truth of Norton’s assertions couldn’t be denied. Two of the stories in the book dated from 1920 and 1921 and were full of “obsolete terms and antiquated expressions,” not to mention “numerous quaint archaisms” no longer acceptable in the modern world. Wrzos embarked on a red-pen exercise of pruning and revision that got him a “good job” from Jenkins and, far more surprisingly, a bonus from Greenberg.

(The passage leaves behind the question of who else Greenberg used as “upper echelon first readers.” In the larger picture, the question of whether Greenberg had an assistant in the two-to-three-year gap between Wrzos and Landis remains open, as does the name. This may be when he employed a secretary with Larry Shaw taking on work the assistant would normally have done. No mention of any helper can be found for Gnome’s last five years.)

Both FPCI and Shasta ceased publishing in 1953, although each tried doomed revivals later on. Fantasy Press managed to stay upright through 1956, but hadn’t been viable for years. Gnome would continue on for almost another decade, but the spark of genius that made the line synonymous with the best in science fiction faded. More than half the books Gnome published appeared after 1953, but with a handful of fine exceptions – most of them, ironically, fantasy – they were lesser titles by lesser names.

Several factors combined to rock the genre, some of them affecting Gnome even more than its competitors. For a short while after the war science fiction had gained respect for its seeming powers of precognition, but the field failed to build on its successes, instead drowning in a morass of stories about atomic wars, telepathic mutants, and alien invasions with thinly veiled political overtones, tales that were essentially rewriting WWII over and over. The Campbell explosion became increasingly picked over and few young powerhouses garnered the acclaim of Campbell’s crew. Those that did were quickly lured to the larger budgets and prestige of the mainstream houses the skimmed the cream off the top of the field. Little information exists about Greenberg’s advances to authors, but they probably averaged around $500. Asimov wrote that he received a statement saying he was owed $950 after payment of “small sums” for the four Gnome books Greenberg did. No money accompanied the statement, but Greenberg promised to pay in weekly installments. “He always paid some,” Asimov wrote, “just enough to whet one’s appetite for one’s own money without really satisfying it.”

No bomb dropped in those atomic war stories left pure destruction behind to match the launching of Doubleday’s Science-Fiction Book Club (in late 1952, although it didn’t really get going until 1953).

ESHBACH says that “in the following year Gnome experienced a 90% drop in sales.” That can’t literally be true – Gnome would have been out of business immediately – but the dropoff must have been severe for all but a few of the biggest names. Doubleday respected Gnome – the vast majority of the early SFBC books had originally been published by Doubleday except for three Gnome titles – but virtually the entire audience for hardback f&sf other than a few collectors and libraries switched over to these cheaper but readily available editions. Little wonder that Greenberg increasingly had to resort to beginning authors and creative use of others’ original product to pad out his line.

Few non-historians recognize the names of F. L. Wallace, H. Chandler Elliott, Arthur K. Barnes, Wallace West, or Everett B. Cole. Tod Godwin is known solely for his short story, “The Cold Equations,” and not for his Gnome novel. Mark Clifton & Frank Riley won a Hugo for They’d Rather Be Right, and were never heard of again. James Gunn, James Blish, James A. Schmitz, and the duo of Robert Silverberg & Randall Garrett went on to bigger careers, though their Gnome books are forgotten. Only the eternal Hoka stories from Poul Anderson & Gordon Dickson, Earthman’s Burden, and the Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories from Fritz Leiber, Two Sought Adventure, live on. Robert A. Heinlein provided the biggest kick to late Gnome when he allowed Greenberg to reprint his 1941 serial Methuselah’s Children and two collection of short stories, The Menace from Earth and The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag. It says everything about the state of publishing genre f&sf as late as 1958 that the biggest name in the field needed to turn to Gnome to get his non-novel material out. Since it was a reprint, Heinlein received only a $500 advance for Methuselah’s, far less than his usual demands.

Far more interesting are the projects that Greenberg took under his wing. He found a magazine oddly called The Complete Book of Outer Space and bound it in hardcovers. He rescued yet another de Camp project, the epic nonfiction tome on the Atlantis myth, Lost Continents, from the bankruptcy of Prime Press. He saw Arthur C. Clarke’s first novel, Prelude to Space, fail as a digest-sized paperback and made it a hit in hardcovers. When master anthologist Groff Conklin’s mainstream publisher refused to issue Science Fiction Terror Tales, Greenberg snapped it up and saw it fly out the door. A deal with paperback publisher Dell got them to do all the heavy lifting of printing Judith Merril’s first four Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy anthologies allowing Greenberg to merely slap hardcovers on them as prestige publications. He did the same with Ballantine for Frederik Pohl’s Drunkard’s Walk. He reached back into the past to replicate his success with Howard and Conan by reprinting from the original plates two ancient tomes by Talbot Mundy, Tros of Samothrace and Purple Pirate. These books were labeled as Fantasy Classic Library rather than Gnome, a device he used to publicize the FCL with a separate series of advertisements. When Fantasy Press ran out of money in a last-minute comeback, Greenberg took two already typeset books, Edward E. Smith’s The Vortex Blaster and Campbell’s Invaders from the Infinite, and said he would finance a printing. (He did: a printing, not two, to Eshbach’s chagrin.) More than a quarter of Gnome’s last fifty books weren’t his originally, acquired and manufactured on the cheap, yielding some of his best sales. Whatever his other faults, Greenberg had a streak of genius shrewdness for running an f&sf line.

Another Big Idea emerged in 1955 with the launch of The Science-Fiction World.

Robert Bloch and Bob Tucker, both long-term big-name fans and big-name authors, teamed up for an unclassifiable production. Part newsletter, part fanzine, part gossip mag, part Gnome advertisement, The Science-Fiction World had super high intentions. As they wrote in the first issue, the objective was:

To design a newspaper in which many thousands of readers to who the term “actifan” has no meaning whatsoever: those who regularly or occasionally purchase science-fiction books and magazines but have not yet discovered the unique world of fandom.

For this reason, we’re hit on a new method of approach. It is our intention to give SCIENCE FICTION WORLD the benefit of mass distribution throughout the bookstores of the nation. In line with this policy, we will endeavor to present material specially designed to acquaint general readers with what’s going on in science-fiction today: news of writing and of writers, items of interest to those who want to learn more about the “inside” of our hobby. [capitals in original]

Another great promotional idea from Greenberg, another overreach in time and money for little return. Bloch wrote that, “This assemblage of fresh news and stale jokes goes to a distribution and mailing group of approximately 30,000 people – several of whom actually seem to read it.” Despite the obvious self-deprecating tone, the assessment proved all too true. The planned quarterly schedule immediately crumbled, with the second issue not appearing for six months. Four more eventually appeared through 1957, the news as stale as the jokes. [Wanted: Four headed girl to model new line of hats.] In true Gnome fashion, a major production mistake marred the project. Both the fourth and fifth issues were marked Vol. 1, No. 4. Nobody noticed, and the sixth and final issue is marked No. 5. Today a full set is the priciest item of Gnome ephemera.

None of the grand plans mattered in the end. Gnome had been a dead man walking for years. In addition to the body blows already mentioned, Gnome had an almost supernatural relationship with its printer, one that propped it up just slightly more than it weighed it down until the balance tipped in 1962 and sank the company.

Bizarrely, Gnome’s end is tied to its beginning, another Gnome mystery: who printed its third title? That’s hugely important because printing costs dominated budgets. The manuscript had to be typeset, printed, and collated. Binding the loose pages in some variant of hard boards was an additional charge. The dust jackets also needed printing and folding, and cost more than interior pages because of better paper stock and the use of color. Kyle’s family press could provide these functions without being terribly good or efficient or cost-effective at any. How long did they stick with it? Gnome was often sloppy with information on its copyright page, leaving out important data. The material about printers abruptly stops after Carnelian and Porcelain, which both explicitly state they were printed by “Advisor Press, Monticello, New York,” i.e., Kyle’s family business. The next several titles simply report “Manufactured in the United States of America.” Stefan Dziemianowicz states that Porcelain was “the last of the press’s books to be published by Kyle’s family printing operation.”

This contradicts CHALKER, who says both that “the first books, up to the Hubbard, were printed using Kyle family connections” and that “Starting in 1950 with Typewriter in the Sky, Gnome books were produced in New York City using H. Wolff & Co.” CHALKER is a major source for information about Gnome and most subsequent writers lift their facts from this monumental work. The problem is that almost every checkable fact in CHALKER is wrong. As the entry subsequently correctly states, Typewriter was a mid-1951 release. An even better case for wrongness can be made by holding Typewriter in your hands, opening it, and seeing that the printer of record was Colonial Press, Inc. So were the previous three Gnomes.

Only twenty years old at the time, Colonial grew to be the largest book publisher in the country, so big that it “had its own hospital, daycare, post office and the Colonial Press Inn, where employees could live.” Despite that provenance, Colonial was sited in Clinton, MA, some 200 miles from New York. Fortunately, they had a convenient branch office on 42nd Street opposite the New York Public Library. The deal they offered must have been very good to offset the shipping costs, for Colonial’s name appears on a half dozen titles in 1951 and 1952, including three of Greenberg’s beloved anthologies.

The H. Wolff Book Manufacturing Company, to give the firm its formal name, was to giant New York what Colonial was to tiny Clinton. It occupied a series of hulking 10-story buildings along and behind West 26th Street.

H. Wolff was printer and binder to the stars; Random House, Macmillan, and the Book-of-the-Month Club were clients, while Grosset and Dunlap and George H. Doran leased space in their buildings. At its peak, Wolff bound 100,000 books a day in New York and had so much business that it moved its printing facilities to cheaper New Jersey. And it had a connection, if a distant one, to the world of f&sf. George Salter was a book designer who created hundreds, perhaps thousands, of covers for books and magazines. He was the art director for Mercury Press from 1939 to 1957. During that time he did every cover for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, more than 500 for their three lines of digest-sized paperback mysteries, other miscellaneous digests, and the early covers for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, right around the time that Kyle was hunting for a new printer. Salter had fled Germany in 1934 and emigrated to America when sponsored by Bertram Wolff, then head of H. Wolff. H. Wolff in fact employed him and gave him his first commission in 1935. If Kyle wanted to talk shop, Salter would be an excellent choice.

The first book printed by Wolff preceded both Typewriter and Colonial: Pattern for Conquest was a 1949 release. Wolff’s name appears nowhere in the book, but its proposal amazingly survives in the Syracuse University Special Collections. The details offer an unprecedented look at the economics of small press publishing in the era.

Type to be set in 11 on 13 Janson, type page size 22 x 33 picas overall. Based on a book of 256 pages, we give you below a resume of the cost of composition, electrotypes, and plastics:

Half title $ 2.52

Ad card 5.88

Title 5.88

Copyright 2.52

Dedication 2.52

Part Title 2.52

248 Pages text @ 1.68 416.64

$438.48

254 Electros – straight text @1.50 $381.00

254 Plastics @ 1.20 304.80

6 Plate boxes @ 2.00 12.00

For the presswork, book will be priced as 4-64 page forms on a 44 x 66” R R Wove (60 Lb.) sheet. Prices for printing are as follows:

3,000 copies 5,000 copiesFrom Plates: $195.00 $245.00

From Type: 280.00 335.00

Paper Text: 380.00 620.00

We shall hold the type for two months free of charge. Our charge will be 3¢ per page for each month thereafter.

For the binding, book will consist of 256 pages, folded and Smyth sewn as 8–32-page signatures, no tips, no tapes, trim size 5-3/8 x 8”, plain full edges, round back, lined up with crash and paper, using 70 pt. Binder’s board, and Novelex cloth, plain white endpapers, stamped with one impression of ink, printed jackets you to supply.

Prices are as follows for binding:

3,000 copies - $0.20-1/2 per copy

5,000 copies - $0.20For a rough front and foot, please add 3/8¢ additional to the above.

For Mactex paper, the above prices will be $0.02-1/4 per copy less.

If Zeppelin cloth is used, please add $.01-1/4 per copy.

Our charge for cartons will be $.35 each.

Gnome used the 5,000 copy printing for Pattern, increasing the total cost. We don’t know which of the other choices were made, so no final total can be made. Several uncalculated costs would swell that total. Binding 5,000 copies at 20¢ each is $1,000. Even if a carton were to contain 50 books, making it quite heavy, that’s 100 cartons or $350.00, and more than 100 cartons were surely needed. Additionally, Gnome was to supply the printed dust jackets, a pricey item. Add to that Smith’s advance, presumably around $500, and more than $3,000 was needed before a book could go out the door. Nor did that include shipping the books to stores and customers. Since Gnome presumably sold the books wholesale to books at the standard 50% discount, or $1.25, the title would have to sell 3,000 copies or so just to break even.

The letter is addressed to Kyle, of course, not Greenberg. He did all the design work and made the printing choices. Greenberg probably is the one who opted for the larger 5,000-copy print run, however. Greenberg always thought big and his uncanny success at bringing in the biggest names made this gigantic number – often more than Doubleday printed for its f&sf – not merely reasonable but conservative. Both Asimov and Clarke went into second and even third printings after the initial run of 5,000. Greenberg’s omnibus Five Science Fiction Novels, from the glory year of 1952, had an initial print run of 6,500, the highest of any Gnome book until Robert Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children in 1958 required 7,500. Numbers like that, unheard of in the small presses, made his move appear genius.

Gnome was riding a high at the time. Pattern would be the first post-war Astounding serial to be put into hardcovers by any of the small presses. It would follow the coup that was Nelson Bond and precede the automatic hit of Heinlein’s Sixth Column. Smith was not as big a name as either of those two but he was the essence of the solid performer that sustains a publisher. Names could only write so many titles; in the mandatory sports analogy, publishers needed singles and doubles as well as the hoped-for home runs.

Were all three titles printed by Wolff? (Were any? I’m making the assumption that the proposal would not have been kept to be included in the archives if someone else got the job. That fails to explain why Wolff’s name does not appear in any, nor why the first acknowledgement doesn’t come for three more books and then in the downsized Castle of Iron but not in the similarly-sized joint July 1950 release Minions of the Moon.) The three books share superficial similarities but February is printed on different paper than the others. That could be explained by its being longer and bearing a higher list price, so better paper to make the volume thinner and more attractive might have been a design choice.

An ounce of truth, as the adage goes, is better than a pound of speculation. One week after the September 6, 1949 proposal from Wolff, Kyle received a similar proposal from Colonial, but for Sixth Column. The proposal is far less detailed with choices, but also far lower in prices.

The costs for manufacturing this title under our A Plan specifications will be:

Composition Janson – 23 x 38 picas overall

8 pages Blanks – –

1 “ Title page @ 5.50 5.50

5 “ 2-½ titles, card, c/r and ded. @ 2.25 11.25

242 “ Text – 11/14 pt. @ 1.22 382.36

399.11

Plates: 248 pages – Copper face @ 1.22 302.56

Presswork: 256 pp. 5-3/8 x 8 – 5000 copies – 201.40

Binding: A Plan specifications – 5000 – per copy .1828

You will supply paper for text, dies and printed jackets f.o.b. our plant.

Again, my assumption is that the proposal would not have been kept until it was accepted. However, Kyle kept nosing around for the least expensive good printer. Notes for Lewis Padgett’s Tomorrow and Tomorrow/The Fairy Chessmen in 1951 show bids from both Wolff and Colonial, with Wolff winning since its name appears in the book. In 1952, Kyle reached out to American Book-Knickerbocker Press to bid on Robert E. Howard’s The Sword of Conan. Nothing in the book indicates the actual printer, but on March 3 Kyle sent an order to Wolff for 4,000 copies. That would seem to settle the matter but every previous source says 5,000 copies were printed. All the subsequent Conan titles are also said to have had printings of 5,000. The two possibilities are that Kyle made a mistake on the order and the later correction didn’t make it to the archives or that Greenberg misremembered years later when he gave the figures to Lloyd Eshbach for his book on small presses. The 4,000 number is in black and white, so I’m forced to accept that. (Nor is ESHBACH a perfect record. His Gnome list manages to entirely omit Pattern.)

One book from Wolff appeared in 1951 and then from 1952’s Sands of Mars on, Wolff was the standard, listed publisher of almost all books Gnome originated. “Almost” because several books have no listed publisher at all and because Greenberg’s 1953 anthology The Robot and the Man states it was printed by Country Life Press. That print shop was part of the mainstream publisher Doubleday’s sprawling complex in Garden City out on Long Island. Garden City is just a couple of railroad stops away from Hicksville, but Gnome’s address doesn’t change to Hicksville until 1958, when Greenberg moved to neighboring Jericho. Proximity therefore doesn’t explain the shift. Nothing else known does either.

In hindsight, Greenberg would have been smarter to leave Wolff, find a small job lot printer, and cut his print runs, maintaining a high-quality line for bookstore and libraries. In 1951 he in fact started print runs of 4,000 for about half his titles. Although all the expected hits stayed at 5,000, too many top authors got stuck with the lower number and too many newcomers had the larger for any glib explanation. Yet even 4,000 was overly large for most authors in the 1950s. Either he couldn’t bring himself to admit defeat or else he was already in too much debt to Wolff to break free. What actually happened was slow strangulation. Gnome books had been known for their good paper, nice bindings, and a variety of fillips to enliven the boards. From 1954 on, Greenberg cut every corner he could. Cheap paper that darkened at first exposure to light appeared all too frequently. The boards apparently were taken from whatever surplus Wolff couldn’t sell to anyone else, in colors that belonged to some alien star’s spectrum. The half cloth backings on Greenberg’s anthologies lost their embossing. Boards were now always bare and uninviting. Covers were drawn by artists just out of school or given to the new and uncredited art director, W. I. van der Poel, Jr., who was a designer but had no flair for actual art.

This seemingly pedantic exercise has hidden import. More than any of the other small presses, Gnome’s business plan was shaped by its choice of printer. While the world of hardcore f&sf readers was deep in its passion, it was narrow in its size. Except for a handful of names, the audience for a hardback genre book was around 2,000-3,000 people. Few of the small presses exceeded that number. FPCI’s print runs were usually 1,000-2,000, Shasta’s 2,000-3,000. Fantasy Press never cracked 5,000 except for Edward E. Smith.

What happens if a publisher prints 5,000 copies of a title but can only sell half? Those extra copies piled up by the thousands. After a year with Wolff, Greenberg dropped down a floor at 80 East 11th Street and took two rooms, one editorial, the other for storage, shipping, and packing. Two more such rooms were soon added. The building, which also included Frederik Pohl’s literary agency whose clientele were the f&sf elite, became the hub for professional f&sf community. Adding extra rooms made business sense in the good years, but cost too much after sales dropped. Greenberg found a workaround for that as well. Printing a book was one cost; binding the pages was an additional one. The storage mentioned above included unbound copies of a title stacked in a corner until the bound copies sold out. At that time, the money they brought in could be used to bind another set of pages and put those out for sale. That explains most of the numerous Gnome variants, titles who appear in as many as five different bindings. (Some of the bindings have a known chronological sequence, although many of the later ones can’t be given dates.) As the number of titles rose into multiple dozens, the lack of space in the building for what must have been tens of thousands of unbound copies became an acute problem. Wolff was willing to warehouse them, but at a price, creating a perpetual cycle of paying Wolff twice for the same book. This was madness in the long run, but justified in the moment by logic that only Greenberg could love. Hence the spiral of debt Gnome fell deeply into.

Greenberg, always ingenious if not always wise, had another idea. Getting books out to the public at discount prices helped to reduce warehousing costs and brought in cash flow. Ads for “PICK-A-BOOK” started appearing in Science-Fiction World in late 1956, although the operation didn’t get going until 1957.

Now you can own brand-new, beautiful First Editions of science fiction books by your favorite authors at a FRACTION of their regular price! You don’t have to join a “Club” … you don’t have to buy any “extra” books … you get handsome, first-class volumes at HUGE SAVINGS! “PICK-A-BOOK” is the new division of Gnome Press, the only full-time, exclusive publisher of science fiction in the country. …PICK ANY BOOKS YOU LIKE … OUR ENTIRE LIST OF TITLES IS NOW THROWN OPEN TO YOU AT ONLY $1.50 A BOOK! …

For still greater savings we’ll send you 3 books for $4.00 … any 6 books for “7.50!

The 36 titles in the ad weren’t exactly Gnome’s “entire list”: Greenberg smartly omitted most of the newest 1956 and 1957 releases. Not for long, though. In early 1958 the ads changed to feature “THE CREAM OF 1957 SCIENCE FICTION BOOKS,” so that a half-dozen brand-new books sold in bookstores and advertised on the back panels of Gnome titles at full list price could now be had for $1.50. This seems counterintuitive at best, yet selling books at half price can bring in more money if more than twice as many books are sold that way. The evidence points to this equivocal success. Gnome released a swath of variant boards for these titles, many of them appearing in 1959 in gray cloth. Each rebinding represented a win/win. To get as many as possible out the door, books sold for as little as $12.00 for 10 titles.