In 1950, Doubleday & Company published Isaac Asimov’s first book, Pebble in the Sky, just ahead of Gnome publishing I, Robot. Doubleday wasn’t just big: it was the biggest. When it started a line of F&SF, every other publisher had to take notice and a good many launched their own lines.

This alone might have been enough to kill off Gnome. Every bookstore owner in America automatically perused Doubleday’s catalogs. They had to go out of their way and make a special effort to find out what Gnome and the other small presses were putting out. Doubleday could afford to advertise and market its books in a fashion an order of magnitude louder than Gnome. Most of all, it paid its authors. Gnome authors rarely saw another penny after they received their advances. Greenberg couldn’t afford to pay royalties; every penny went back into the business. Asimov allowed Gnome to republish the old Foundation stories; he took his new works to Doubleday. Others followed.

If that weren’t enough – and it may not have been, given the continued star power of Gnome’s roster – Doubleday had the money to accomplish something that Greenberg desperately wanted to do but could never really pull off. In 1953 they started the Science Fiction Book Club.

ESHBACH says in his chapter about Gnome that in

November 1948 a Fantasy Book Club “Bulletin” was published as a sort of miniature news magazine about the club, its selections and items of general interest. … The FBC continued limping along for several years, but it was never really successful. … Conceived primarily to sell Gnome Press books, it used selections from other publishers as well, purchased as I recall it, at a 50% discount. They made special offers including premiums, and they did sell books. Whether the club created new customers or simply deprived the other specialist publishers of direct sales is an open question.

These are extremely rare and I was amazed that one came up for sale so I could grab it for my collection. (see Other Ephemera for a longer look)

Greenberg also took out ads in magazines at around the same time, because one appears in the November 1948 issue of Fantasy Book.

It’s harder, impossible actually, to find a direct mention of the FBC in the mainstream press. A search through newspaper archives pulls up one possible indirect mention, from the Greenville [MS] Delta Democrat Times, February 26, 1950. In a column on their Critic’s Page, which mostly dealt with books, readers got “News from the William Alexander Percy Memorial Library.” A whole, intelligent, approving column on science fiction, something that is uncommon even today.

Since the bomb exploded over Hiroshima the demand for science fiction has boomed. There are eight pulp magazines concerned primarily with science fantasy, ten small publishing houses handle nothing but fantasy books; over fifty science fiction novels have appeared in hard covers since the jar, and there is even a science fiction book club!

…

Most readers of science fiction are men. The proportion of women readers is just about that of women scientists and technicians. Like the readers, most writers are men. Many are prominent scientists writing under pen names.

Science fiction has its cultists who form clubs, go to world conventions – the sixth of which was held in Toronto last summer – and who circulate among themselves mimeographed rave sheets of “fanzines.” These fans collect their “classics” so feverishly that a recent issue of Antiquarian Bookman was devoted entirely to them.

Can anyone enjoy these stories? Well, anyone who can accept the wild improbabilities of yesterday’s science fiction that have become today’s realities. Today’s science fiction asks the reader to accept notions only slightly wilder, and then proceed to enjoy stories that are subtle, frightening or humorous. It can be a tonic to the imagination and thus prepare us to accept whatever might be ahead for us in the world of Tomorrow.

Easy to see under all the politeness how weird science fiction and its readers looked to contemporaries. The boom must have been notable indeed to get mainstream publishers willing to dip their toes in such muddy waters.

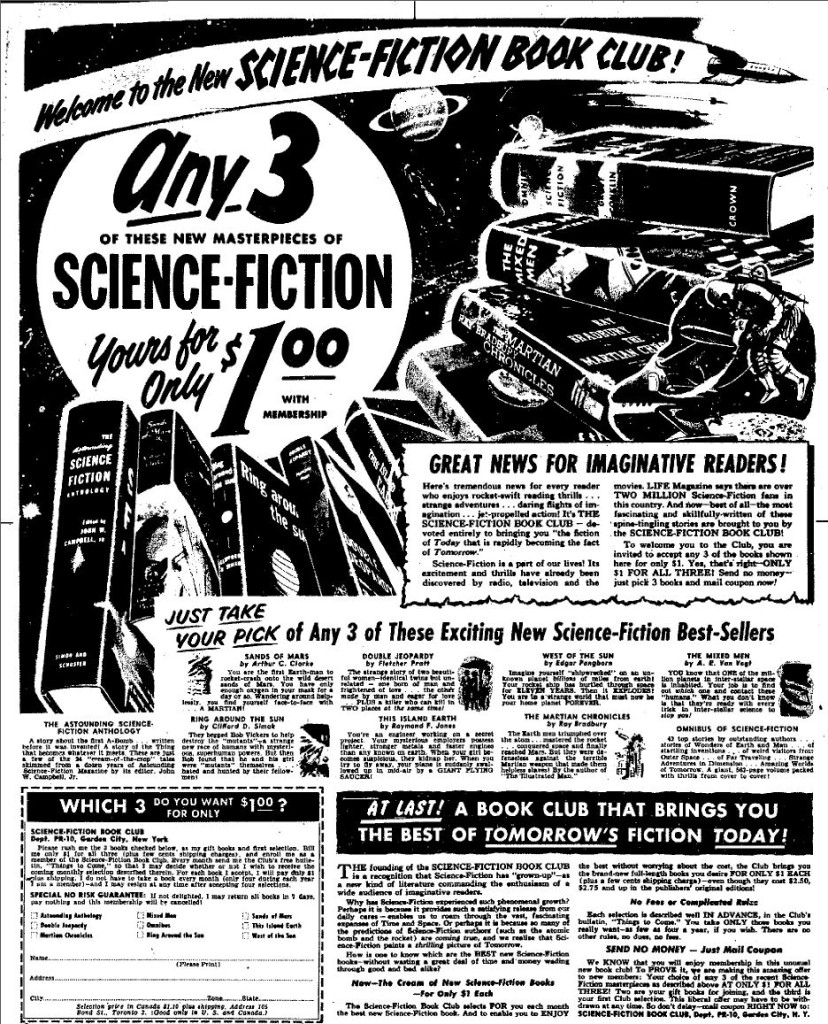

Doubleday started its Science Fiction Book Club – note the name: by 1952 Science Fiction had surpassed fantasy and science fantasy not merely as the dominant genre but as the generic name for the field of f&sf – in March 1953. (ESHBACH says it announced plans for one in 1949; if so I don’t know why there would have been a four-year wait. No hits can be found on the phrase in newspaper archives I searched before 1953.) A new lead selection would be issued every month for the rest of the fifties and sixties, until they started issuing two or more from July 1969 onward. But you can’t start a book club with a single title. That first announcement included ten other titles already available. In a game of turnaround is fair play, these included two Gnome titles: The Sands of Mars by Arthur C. Clarke and The Mixed Men by A. E. van Vogt. Isaac Asimov’s Second Foundation was the book-of-the-month for November 1953. (KEMP has a check list of all Gnome titles that puts a check in the box for SFBC next to Asimov’s Foundation, but I know of nothing to confirm that. Since that box is next to the one for The Mixed Men I suspect it was just a typo.) In a way this was a great compliment to Gnome’s appeal. About half the early SFBC books were republished from Doubleday itself, and almost all the rest were from other major publishers. (Technically, the SFBC originated from Nelson Doubleday, Inc., a subsidiary imprint of Doubleday and Company; I’m hoping this will be the smallest nit I will ever pick.) Only Shasta among the other small presses rated even a single selection – Raymond F. Jones’ This Island Earth.

As a compliment it was deadly. ESHBACH claims that Gnome’s sales dropped 90% the year after the SFBC began. Not least among Doubleday’s advantages was that, instead of half-page ads in the smallest of f&sf magazines, it could afford to take out full-page ads in newspapers.

Could it get worse for Gnome? Yes, and quickly. The Fantasy Book Club was undoubtedly helpful to fans who couldn’t find books locally. Unfortunately the number of titles was small and so was the discount, one book free for every two bought, or $12.00 for six books, because these were the original editions from a middleman. The SFBC offered a larger selection and a fantastic price. Books were not list price as with the FBC, but merely a dollar each, and that after the three books for $1.00 that came one’s way merely by joining the club. Your first six books therefore only cost $4.00. Hardly any fan cared that the books were reprints, often smaller and more cheaply put together. What was important was that they appeared before any paperback version was available, often years before, making the SFBC almost mandatory for any young fans who wanted to read new books but couldn’t afford to pay three times as much for the original edition – assuming that any could be found in the first place. The SFBC made them available in your mail box. Generations of fans got hooked on f&sf this way.

∞

The Science Fiction Book Club Gnome Reprints

The SFBC edition of The Mixed Men is the same physical size as the Gnome original, with the same number of pages, identical type on the boards, though the BCE is cloth and a very dark green instead of black boards, and identical prose on the front flap. The original uses better paper that was slightly thicker and hasn’t darkened as much. (The darkened spine is a scanner artifact.) A few minor changes are made before the text starts on page 9. The pre-title page on the BCE moves the title farther up on the page; the words “Gnome Press/New York” are moved up on the title page; The words “First Edition” along with all other Gnome-specific information are removed from the copyright page; and one entire leaf listing Other Books by the Author has been omitted. The rear flap is blank; the rear cover has the standard wordage about the popularity and appeal of science fiction that was shared with other promotions like the newspaper ad and used uniformly on all SFBC editions of the time.

The SFBC edition of The Sands of Mars has almost identical similarities and differences. It’s the same physical size as the Gnome original, with the same number of pages, same type on the boards, though the BCE is cloth and a dark maroon instead of red boards, and identical prose on the front flap. The original uses better paper that was slightly thicker and hasn’t darkened as much (again, the spine darkening is from my scanner). A few minor changes are made before the text starts on page 3. The pre-title page on the BCE moves the title farther up on the page; the words “Gnome Press Inc./New York” are moved up on the title page; The words “First Edition” and information about the printer are removed from the copyright page; and one entire leaf listing Non-fiction books by Arthur C. Clarke has been omitted. The rear flap is blank; the rear cover has the standard promotional wordage.

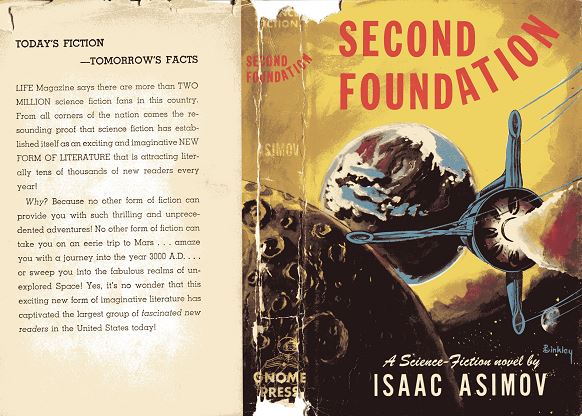

The SFBC edition of Second Foundation is a different beast entirely. It uses the original Gnome cover, standard practice for SFBC editions. The type-only covers for the two earlier Gnome reprints are unique even among the pre-publication releases and I can’t imagine why the change was made. The paper itself is also very different. While Second Foundations’s coverstock is stiff, calendared heavy paper, much like all other normal dust jackets, The Mixed Men and The Sands of Mars used what can only be called construction paper, taken from a kindergarten. This BCE has also been resized and replated. It stands 8.5 inches tall instead of 8.25″ for the Gnome edition, although the width of 5.5″ is the same. Oddly, the BCE doesn’t take advantage of the extra height: it has only 36 lines per page while the original has 39 lines per page. The last page of the BCE edition is numbered 224; the last page of the original is numbered 210. That’s misleading, though, since in the original the “Prolog” is numbered vii, and the first page of the main text is page 3. In the BCE the “Prolog” starts on 7 and the main text on 13. The Contents pages are therefore numbered differently from start to end and the interludes in part i are also handled differently. The By Isaac Asimov list of books on the reverse pre-title page is omitted; so are the words “First Edition” and “by H. Wolff” on the copyright page. The boards are blue cloth, a lighter blue than those on first state Gnome edition. The BCE is noticeably thinner than the Gnome. The rear flap is not quite completely blank; “Printed in U. S. A.” appears at the bottom. That statement was moved off the rear cover, which is otherwise identical to the two earlier Gnome BCEs.

Does anyone know of any complete lists of monthly Doubleday Science Fiction Book Club Selections (SFBC going back to its inception)?

Not sure if this will get to you, but wikipedia has a list. I was looking myself.