Comments

Edward Groff Conklin (1906-1968) had the attention span of a mayfly, passing through Dartmouth before graduating from Harvard, and then flitting among dozens of jobs – most, but not all, connected with books – in a crowded lifetime. While an assistant manager at New York’s Doubleday Bookstore in the 1930s, he compiled anthologies of stories from two fabled magazines, Smart Set and The New Republic. A decade later he persuaded the mainstream publisher Crown to do a gargantuan anthology that was published in 1946 as The Best of Science Fiction, containing 40 stories in its 785 pages plus a preface by John W. Campbell. Conklin had proposed the anthology in 1944, getting nowhere. The sudden shift of society into the Atomic Age in 1945 made the publishing world blink, forcing it to reconsider science fiction as a possible viable medium of literary expression that illuminated elements of the present in a way no other literature had managed. The appearance of Best in hardback, followed a few months later by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas’s even-heftier Adventures in Time and Space from Random House, gave science fiction an imprimatur that book people could not ignore. (The 1943 Pocket Book of Science Fiction, edited by Donald A. Wollheim, was doomed by its paperback publication to be ignored by bookstores and newspaper reviewers.) These two books (especially their heavy reliance on Campbell’s Astounding as a source) set the stage for acceptance of the dozen specialty hardcover f&sf presses that would raid Campbell’s regulars for material for the next decade.

Astounding was less of a force in 1950s, with Galaxy and F&SF opening doors to a wider range of storytelling. Though Conklin included some Campbellian classics, half the stories in Terror were from the 1950s and contained the first stories from F&SF to appear from Gnome. Whether Greenberg couldn’t adapt or just saw that others understood the new field better, he never did a fiction anthology after 1955’s All About the Future, released a month before Conklin’s Terror.

Although Conklin had full-time jobs during this period, he apparently did nothing in his off-hours but read. Another dozen anthologies of science fiction, horror, and the supernatural appeared in the decade between Best and Terror. He also was the book reviewer for Galaxy from its beginning until 1955. In whatever he considered his spare time he edited the low-cost Science Fiction Classics line of reprints for Grosset & Dunlap from 1950-1952. If you ever see a copy of I, Robot with Gnome’s iconic dust jacket printed in green instead of red, you have an SFC reprint rather than a collector’s item.

Gnome Notes

Which came first, the paperback “reprint” or the hardcover “original?” KEMP gives a wry, “Published all of nine days before the commercial paperback reprint.” I haven’t found any source for that claim. Though it may of course be true, the evidence points to a later publication. The copyright page on Pocket Books 1045 shows “published March 1955/1st printing January 1955.” All Pocket Books had dual dates like this one, with the date of publication always after the date of the first printing. Tellingly, however, no date of an original hardback edition is given, which was their norm on a reprint. Moreover, the publisher listed in the Catalog of Copyright Entries is Pocket Books, Inc., which for me is conclusive. The originator makes the copyright claim, not the reprinter. Dell Pub. Co. would be the publisher on the Judith Merril anthologies Gnome “simultaneously published” and some of those paperbacks are known to have preceded the hardback. It looks to me as if, prefiguring the deal made with Dell, Greenberg had Pocket Books set the type for a paperback edition, which he simply reused, adding lots of margin space on all four sides for bulk appropriate to a hardcover edition. In support of KEMP, Pocket Books did acknowledge the connection, saying “An edition of this book in a more permanent binding has been published by Gnome Press and can be obtained from your local bookseller.” That phrasing could be used on a slightly earlier, slightly later, or simultaneous printing, though.

The copyright registration is dated February 15, 1955, which conforms to the March date of publication. The first mention of the book I can find in a newspaper is March 6, also a normal amount of lag after registration. This appears in what is obviously a press release of new reprints sent out by Pocket Books and widely published. Not a single mention of Gnome can be found before April 27, although on March 29 a newspaper reported that the local library added the book. A library almost certainly bought only hardbacks in this era.

Weirdly, however, Robert Frazier reviewed both Terror and Greenberg’s All About the Future, whose copyright registration date was January 15, 1955, in the February 1955 Fantastic Universe. Monthly magazines normally appeared on newsstands early in the month before the cover date (a sell-by date that was a signal of when to pull the magazine for a newer one rather than an indication of its publication). All the copy had to be locked down and sent to the printer several weeks earlier. That requires Frazier’s column to have been handed in sometime in 1954. Only the receipt of advance copies can make this possible, not normally a Gnome practice. Another mystery.

Some of all these mentions must have been good advertising. Terror had the shortest stay on back panels of any Gnome release. It appeared only on 1955 and 1956 titles and was never seen again afterward, implying that the edition sold out amazingly quickly. CHALKER says that the anthology was pitched to Conklin’s standard hardback publisher, Crown, but that they rejected it because it was deemed too scary for school libraries. Good luck for Gnome.

Mixed luck for Conklin. Didn’t matter how famous you were, Gnome could typo your name. All five new titles Gnome released in 1956, along with the second printing of Foundation and Empire, carried back panels that would misspell Conklin’s first name as Grof.

Contents and original publication

• “Introduction,” Groff Conklin (original to this volume).

• story introductions, unsigned, presumably by Groff Conklin (original to this volume).

• “Punishment Without Crime,” Ray Bradbury (Other Worlds Science Stories, March 1950).

• “Arena,” Fredric Brown (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944).

• “The Leech,” Robert Sheckley (Galaxy Science Fiction, December 1952 as by Phillips Barbee).

• “Through Channels,” Richard Matheson (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, April 1951).

• “Lost Memory,” Peter Phillips (Galaxy Science Fiction, May 1952).

• “Memorial,” Theodore Sturgeon (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1946).

• “Prott,” Margaret St. Clair (Galaxy Science Fiction, January 1953).

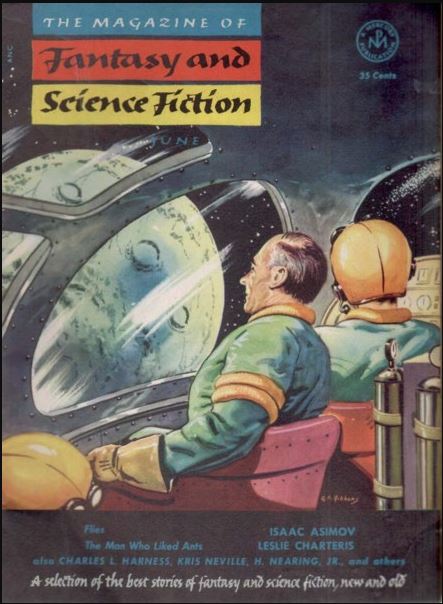

• “Flies,” Isaac Asimov (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, June 1953).

• “The Microscopic Giants,” Paul Ernst (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1936).

• “The Other Inauguration,” Anthony Boucher (The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1953).

• “Nightmare Brother,” Alan E. Nourse (Astounding Science Fiction, February 1953).

• “Pipeline to Pluto,” Murray Leinster (Astounding Science Fiction, August 1945).

• “Imposter,” Philip K. Dick (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1953).

• “They,” Robert A. Heinlein (Unknown Fantasy Fiction, April 1941).

• “Let Me Live in a House,” Chad Oliver (Universe Science Fiction, March 1954).

Reviews

Villiers Gerson, New York Times Book Review, April 24, 1955

Not only the most indefatigable of science fiction anthologists, Groff Conklin is one of the best. His newest collection would seem, by its nature, to impose a limitation upon his stories, as a matter of fact, the result is the opposite. Mr. Conklin professed aim is to raise goose pimples on the reader. Through deft and unerring selection he has succeeded.

Unsigned, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1955

Though many [of the stories] are macabre or gruesome, it would appear that terror is as hard to create in fiction as humor, and science fiction has few writers able to accomplish either successfully.

Bibliographic Information

Science Fiction Terror Tales, Edited by Groff Conklin, 1955, copyright registration 15Feb55, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 55-6842, title #47, back panel #29, 262 pages, $3.50. 5000 copies printed. Hardback, maroon cloth, spine lettered in black. Jacket Design by Ed Emsh. “First Edition” on copyright page. Manufactured in the U.S.A. Printing & binding by H. Wolff. Back panel: 39 titles. Gnome Press address is given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

Variants

None known.

True first edition

Pocket Books 1045 (New York: Pocket Books, Inc., 1955).

Images