When you open any page on this site, the first thing you’ll see is a strip of fantastic – fantastic as to content and fantastic as to quality – artwork across the top of the screen. These are extracts from the Gnome Fantasy Calendars, randomized in some secret NSA laboratory and different every time you view the page. I’ve seen them hundreds of times and they thrill unceasingly.

The idea for a calendar, especially one featuring the biggest names in fantastic pulp art, came out of the first super-enthusiastic brainstorming sessions when Marty Greenberg and Dave Kyle founded the company in 1948. Gnome would publish great books. Gnome would start a Fantasy Book Club (FBC) to ensure that readers would know the titles and be able to order them directly from the publisher. Gnome would publish a FBC Bulletin, a fanzine-like account of the publishing world. Gnome would help the other nascent publishers by including them in the FBC. Gnome would give away one of its titles for every two books sold through the FBC. And Gnome would sell a Fantasy Calendar consisting of all-new art by legendary names.

None of their rivals thought this grandiosely, presumably because they knew they didn’t have the time, money, or personnel to pull all these rabbits out of their hats. Neither did Gnome in the long term.

In the short term, Gnome stunned the tiny world of fandom by making good on every extravagant promise laid out in their first ad, in the Fall 1948 issue of the semi-prozine Fantasy Book.

Fantasy Book was essentially the house organ for William Crawford’s small press Fantasy Publishing Co., Inc. That one issue is historically important because Crawford persuaded other small press publishers to take out their own ads. (And never again. Probably the return was too tiny. At the time Fantasy Book’s small circulation, irregular publication, and Los Angeles base meant that only the inner core of fandom saw the contents and those readers could grab the same information elsewhere.)

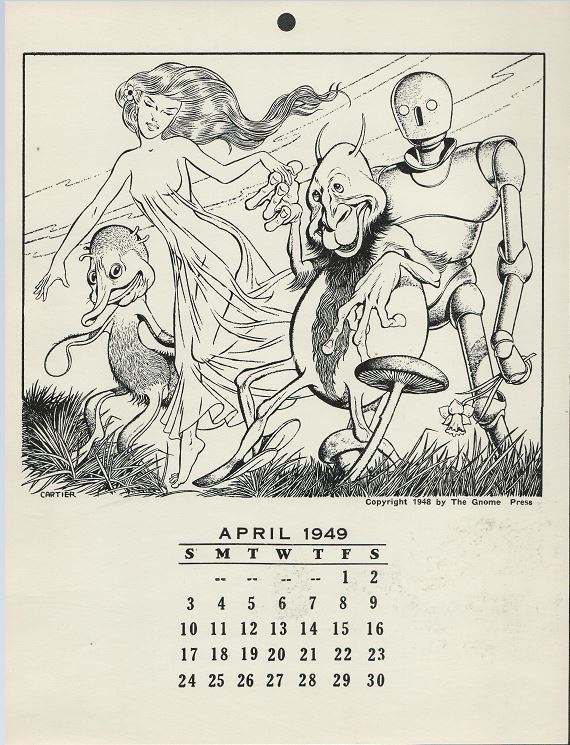

The ad tantalized with its offer of “Twelve illustrations By Edd Cartier & Hannes Bok,” two artists who could hardly be less alike in style but were perpetual fan favorites. Calendars have a short shelf life, seemingly even smaller in 1948 than now. They didn’t go on sale as early in the year as they seem to today, but were geared toward being Christmas presents, with the leftovers sold, often at a discount, to the holdouts who in January realized what they had missed. The last ad for the 1949 Fantasy Calendar I can find appeared in the February 1949 Astounding (which would have hit newsstands in January). This ad amended the text to read, “Illustrations by Edd Cartier, Hannes Bok, and Other Artists.” (Well, “Illustrotions by Ed Cortier, Honnes Bok and Other Artists. Maybe that typeface is extremely wonky but to my eyes the “a” in “and” is noticeably different.) The “Other Artists” meant one piece by Frank R. Paul. His not being named earlier presumably meant that the calendar was still being put together when the first ad deadline passed. “Announce first, produce later” worked as a motto for the small presses as well as it does for modern internet start-ups.

Nevertheless, the FBC Bulletin extolled the unproduced calendar in extravagant terms. The chutzpah needed to call a half-done concept from a brand-new concern as a “collector’s item” is a high point in the illustrious history of hype. Historians will note with particular glee that not one of Edd Cartier’s touted illustrations appeared in the actual calendar.

The calendar’s $1.00 price – an expensive indulgence given that a Gnome hardcover book went for only $3.00 and magazines were still a quarter – needed to be justified by a lavish presentation, something that Gnome was in no position to afford. Instead, buyers received thirteen sheets of card stock, bound only by a bit of string tied through a hole punched at center top. At 7.5” x 10” the pages were slightly smaller than a pulp magazine and not nearly as impressive as a gaudy color pulp cover, since all the illustrations were in black and white. Still, the illustrations were new and unavailable elsewhere, 6 months of Bok, 5 of Cartier, and a September alien landscape by Paul.

Bok also got the cover position, a gorgeous portrait of a variety of alien forms centered on a lush alien female with large tusks protruding from her kneecaps. Only Bok could have made that image work. It apparently is the one older work that Gnome appropriated, having first appeared in the New Collectors Group edition of The Fox Woman and The Blue Pagoda that Bok illustrated, the giveaway being the 1946 date affixed despite that it was also billed as “Copyright 1948 by Hannes Bok.” (see The History of Gnome)

The pages have the usual signs of hasty or non-existent copyediting, as with the use of multiple typefaces for the various copyright lines. Each page was also hole-punched individually, leading to the inevitable misalignment of holes, so that the pages do not form a neat block when bound.

No matter. In 1948, a fantasy calendar with art of this caliber hit fandom right in their “new and exciting” lobes. The response must have been encouraging. Although Stefan Dziemanowicz (“A Gnome There Was: The Gnome Press Story,” The Weird Fiction Review 9, Fall 2018) refers to them as “primarily throwaway promotional items,” I would consider them too expensive a production to be handed out that lightly. Additionally, Gnome’s Fantasy Book Club Bulletin already inhabited that niche. A search of online fanzines makes no mention of the calendar as a promotional item. Or at all, truthfully. We have no indication whether it was released before 1949, let alone in enough time to send as Christmas gifts as the FBC Bulletin suggested.

All I can tease out of what history remains are two inferences: The Fantasy Calendar didn’t sell and the Fantasy Calendar was very popular. If you think your life is hard, try being a Gnome historian.

Enter Julius Unger (1912-1963). Unger came to fandom even earlier than Dave Kyle. In 1929 he was one of the founding members of The Scienceers, New York’s first organized fan club, whose meetings were held in Harlem at the house of black fan Warren Fitzgerald. Unger was a fanatic collector, wrote fanzine columns about collecting, and boasted in a 1947 classified ad in Popular Science about “The world’s largest collection of science fiction and books.” He put out 200 weekly issues of his newsletter The Fantasy Fiction Field and burned out on active fandom to strive to be the field’s pre-eminent dealer.

The April 1949 issue of Astounding contained his first full-page ad, and included a bonus section called, with no guile, “This is for FREE – No Money.” A dozen items were listed, each of which would be sent free to anyone buying $5.00 or more of other merchandise, easily done with the order of two books or a few magazine back issues. Number 4 was “The Fantasy Fiction Field Calendar for 1949 – Art Work by Bok, Paul & Cartier.” The fame and popularity of these artists might be attributed to a coincidental use of their work but by September the caption changed to the forthright “Fantasy Calendar for 1949,” presumably after a phone call from someone at Gnome. (The May ad offered “An original illustration by Cartier for the Fantasy Calendar for Month of April” at a steep $15.00. It must have been snapped up immediately: the line was missing from the June ad.) Giving away free material with the purchase of books smacks of a book club. Sure enough that September ad was headlined “Julius Unger Introduces The Fantasy Fiction Field Book Club, no doubt seeing an opportunity now that Kyle’s feeble FBC was long gone.

The clear implication is that Gnome was stuck with hundreds – thousands? – of Fantasy Calendars and needed to claw back some return on that lost investment. Most likely Greenberg sold them at wholesale to Unger, because Unger’s ads not only offered them as a premium but also as a separate line item for the original price of $1.00. The consummate self-promoter, he overprinted the cover with “This Fantasy Calendar for 1949/sent to you with the compliments of/JULIUS UNGER/FANTASY FICTION FIELD./Box 35, Brooklyn 4, N. Y.” Unger’s version is immediately discernable from Gnomes even without the cover. His has two holes punched for the string instead of one. Therefore he must have started with unpunched, unbound, still-in-the-boxes originals, evidence that sales must have been far lower than expected.

How can I say that the calendars were popular if all that is true? Because Gnome started the whole cycle over again and did a Fantasy Calendar for 1950.

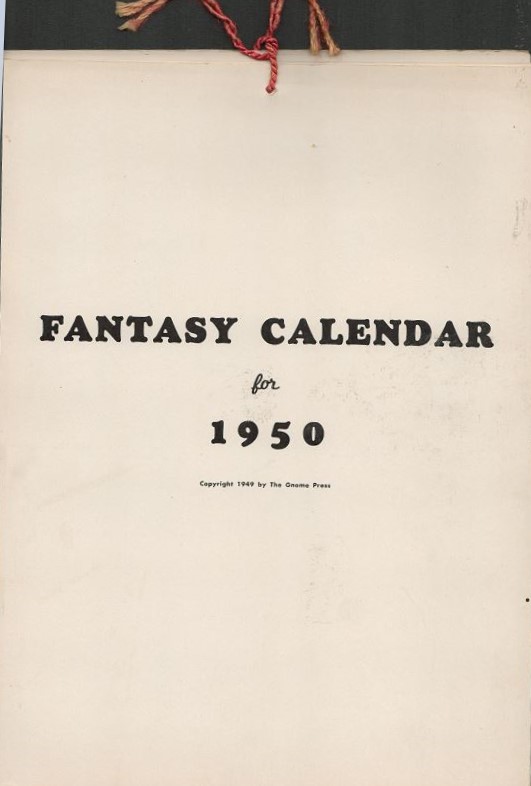

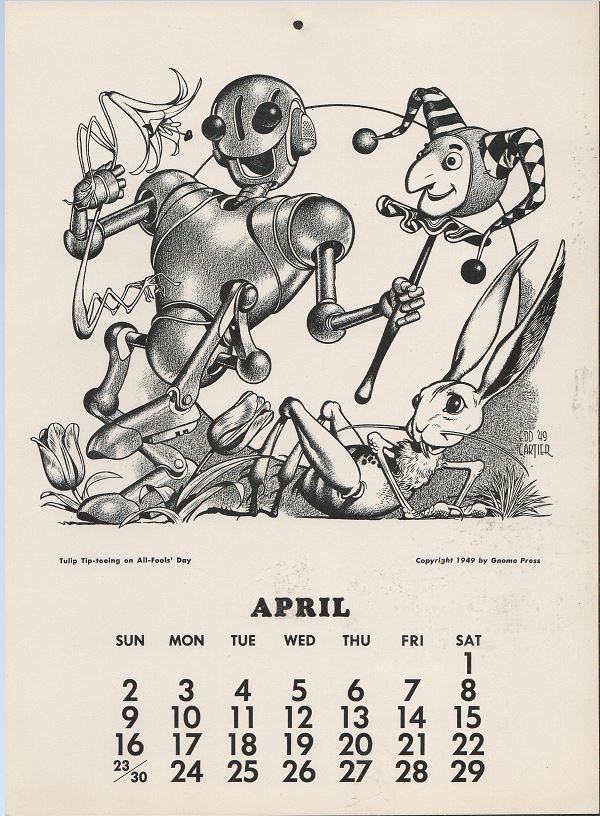

Sadly, Gnome had no extra images lying around to use as a cover illustration, that or they wanted to save 1/13th of the cost of printing. That seems unlikely as the calendar was physically larger – 8″ x 11″ as opposed to 1949’s 7.5″ x 10″, used better printing with much darker blacks, bulked up the calendar to make it more readable, and corrected all the font mishaps. Both Cartier and Bok were given five months, with Paul bumped up to two.

Ads for the 1950 calendar started earlier in the year. Gnome dropped an ad into the Program Book of the Cinvention, the annual Worldcon being held in Cincinnati in September 1949.

An ad in Astounding called the calendar “An Ideal New Year’s Gift!” That might have been true, although greatly spoiled by the fact that the ad didn’t run until the February 1950 issue for the usual inexplicable reasons.

Unger jumped in a few months later, with his ad in the July 1950 Astounding listing “Fantasy Calendar for 1949 & 1950” among his premiums.

Nor was he alone is reselling the calendars.

That gorgeous Bok drawing appeared as November in the 1950 calendar; the ad took up the back page of the June 1950 (#26) issue of the Mexican science fiction magazine Los Cuentos Fantasticos. The text and its Google translation:

El dibujo que aparece en esta página, es una pequeña nuestra de las 12 bellisimas illustraciones que tiene cade uno de los meses del año, y que se deben al pincel de los grandes artistas Bok, Cartier y Paul. El tamaño del calendario es mucho más grande que el actual tamaño de “Los Cuentos Fantásticos”. [The drawing that appears on this page is a small one of ours of the 12 beautiful illustrations that have every one of the months of the year, and that are due to the brush of the great artists Bok, Cartier and Paul. The size of the calendar is much larger than the current size of “Los Cuentos Fantásticos”.]

The calendar is available for one American dollar from Weaver Wright. Perhaps not coincidentally, Weaver Wright also has a story in the issue, “No Hay Tiempo Como el Futuro” (“No Time Like the Future”). That makes Weaver Wright easy to track down as a pseudonym for Forrest J. Ackerman, the multitudinous fan, agent, sf historian, and dealer who we know sold Gnome titles on the west coast. He must have thought that an ad was worth the money because this was a repeat. He had done the same thing the previous year on the June 1949 (#14) issue to sell the 1949 calendar.

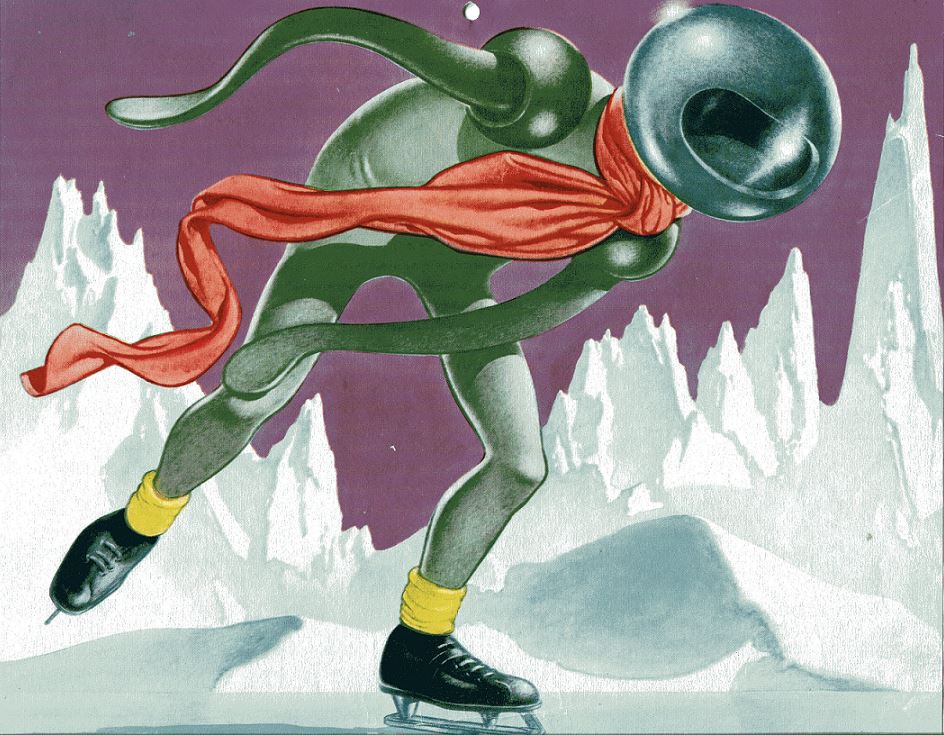

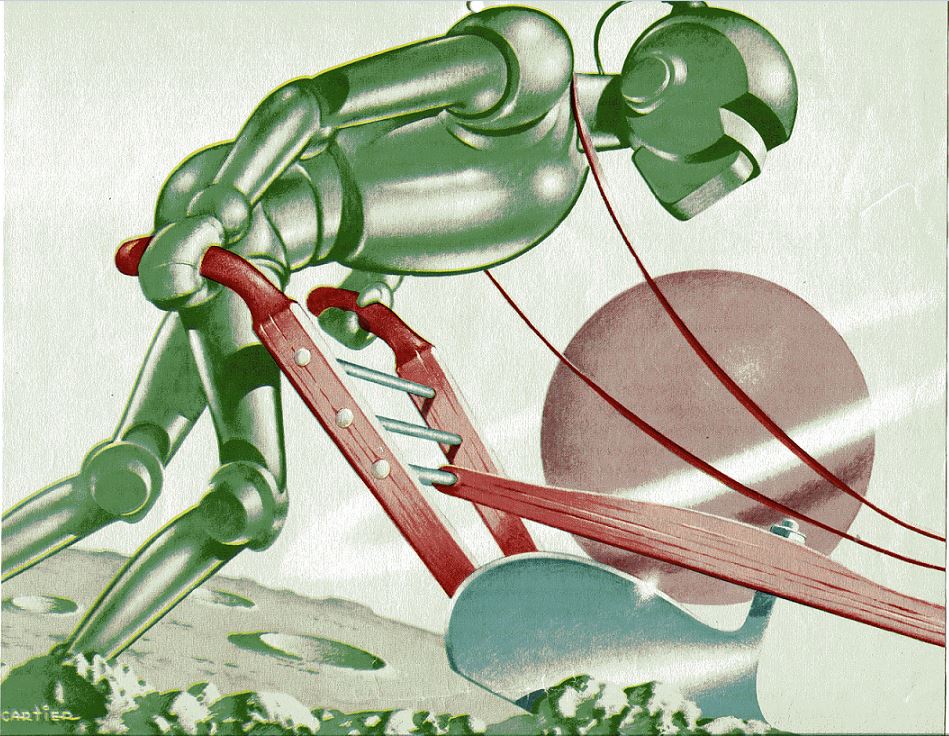

The next news fans received appeared on the back panels of the two Fall 1951 Gnome titles, Foundation and Tomorrow and Tomorrow/The Fairy Chessmen. “AND BY POPULAR REQUEST!/FANTASY CALENDAR FOR 1952/Four full-color illustrations/by Edd Cartier” The blurb read, awkwardly, “the renown” [sic] science fiction and fantasy artist Edd Cartier has drawn four imaginative scenes to illustrate the seasons of the year – beautifully colored and perfect for framing. Here is something you will enjoy for a year – or a lifetime.”

An annual release wouldn’t be bannered “by popular request.” Only a missing item fans wanted to have return gets that headline, a definite indication of the popularity of the calendars. Moreover, these two identical back panels are the only ones that mention the calendars at all.

Something sounds familiar about the description, however. Four illustrations by Edd Cartier. Didn’t the FBC Bulletin talk about four Cartier illustrations of the four seasons? Open the Fantasy Calendar for 1952 and one sees four calendar pages, marked Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. Aha. Certainly these are the same four, valuable illustrations sitting in the files, begging for use. That the Bulletin mentioned black and white drawings is easily swept away, on the word of Kyle himself, quoted in COKER, that the color was added by the technician at the invaluable Lloyd Eshbach’s Reading, PA plant. The oversized pages measure a full 11″ x 17″, with the text cover on slick paper and the four calendar pages on a strange textured stock.

The result was staggering beautiful and today staggeringly rare. I have not seen a copy for years. None of the images are online. I present them here as historic artifacts you’ll probably never see elsewhere.

Gnome wouldn’t be Gnome without an accompanying embarrassing blooper. The 1952 calendar proudly features it on the front page.

The type is taken directly from the front cover of the 1950 calendar with only one change, updating 1950 to 1952. Unfortunately, two changes were required. The Copyright needed to be changed from 1949 to 1951. Fortunately, each individual page had the proper year emblazoned.

I obviously skipped a year, the year of the missing calendar that so upset fans. What about 1951? It is completely certain that Gnome did not issue a fantasy calendar for 1951. Nevertheless, I own it. Not for the first time in Gnome history, as anyone reading through the Books section will understand, we descend into complete madness.

CHALKER, who was working with the best information available at the time, had this to say about Gnome calendars.

Gnome Press also issued calendars for the years 1950-1956; all of them contained both original art and illustrations from the books by major artists and are art folios in their own right. Although they printed up to 10,000 copies of each calendar, most appear to have been thrown away at the end of the year, although Julie Unger of FFF [the fanzine Fantasy Fiction Field] got hold of a bunch of outdated ones from Greenberg in the late 1950s and sold them as art folios! In thirty years of collecting, we have seen only a few in private collections and virtually none have appeared for sale after Unger ran out…

For 30 years historians working on Gnome have cited this paragraph, explicitly or implicitly. When only a single source exists, and that source appears to be thorough and creditable, it deserves to be cited. I’ve been forced to cite CHALKER often, although I’ve equally often found additional material to question their pronouncements. I’ve doing so again. Every “fact” in that paragraph is flatly wrong or impossible to corroborate. The calendars started for the 1949. None of them contained other than original art, although the cover page for 1949 had been previously used. It seems completely unlikely that as many as 10,000 could have been printed, given their scarcity today and the expense that would have sunk their finances. Unger never sold them as art folios and did not sell outdated copies in the late 1950s. The internet provides easy access to at least the 1949 calendars.

It is the sentence that calendars were issued through 1956 that causes the most consternation. Not a particle of evidence exists that a 1953, 1954, 1955, or 1956 calendar emerged from Gnome, although even their hint has, I’m sure, engendered frenzied searches for decades. They don’t exist. They can’t exist. And neither does the phantom 1951 calendar.

Except.

This listing appeared in L. W. Currey’s book catalog:

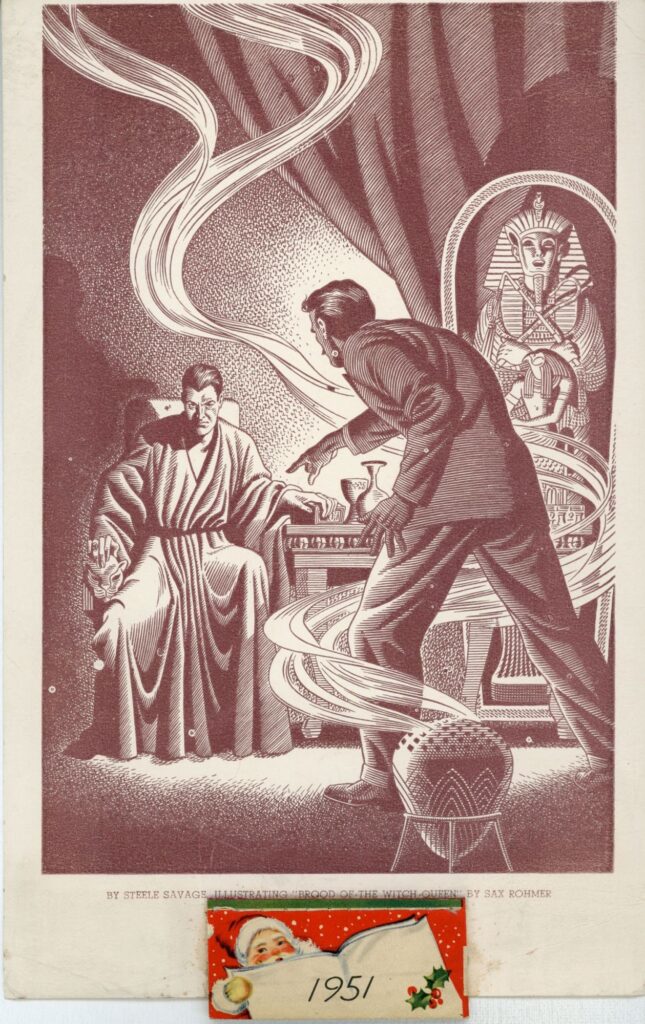

(Gnome Press). [THE GNOME PRESS’ FANTASY CALENDAR FOR 1951.]. N.p., n.d. [1950]. 23.6×15.1 cm. single leaf. A tiny calendar dated 1951 (2.8x 6 cm) is affixed to a print captioned “By Steele Savage illustrating ‘Brood of the Witch Queen’ by Sax Rohmer.” The ultimate Gnome Press rarity. A fine copy. You will probably never see another copy of this.

So I bought it.

Currey told me that “the provenance is the Donald A. Wollheim papers” for proof that this is a true Gnome Press calendar. Whatever this is came from Wollheim’s collection. (By sheer coincidence I happen to have a Gnome book stamped with Wollheim’s name, so presumably also from Wollheim’s collection.)

The 5.2″ x 8″ illustration mostly fills the 6″ x 9.2″ cardstock, with the 2.4″ x 1.1″, 12-page calendar featuring a hearty Santa Claus set right up to the lower serifs of the caption type. Unlike the whimsy of the earlier Gnome calendars, this image is a strong confrontation scene, full of menace and mystery. As a full-page magazine illo, it would jump out at readers.

It would in Famous Fantastic Mysteries, a magazine which existed solely to reprint moldy fantasy classics, like Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Disintegration Machine” from 1929 and A. E. Coppard’s “The King of the World” from 1921, both of which appeared in the January 1951 issue. So did Sax Rohmer’s 1918 “Brood of the Witch-Queen.” The story occupied the uncredited cover, which combined King Tut with a Hollywood version of Cleopatra, as stereotypically Egypt as any American audience could envision.

Open the magazine and what you see will startle and astonish you! No interior illustrations appear. None. Zero. Not by Steele Savage or anybody else. Nevertheless, the art clearly was meant to illustrate the silly Egyptian nonsense that constitutes the story. I waded through it so you wouldn’t have to.

Wha’ hoppened? A little digging reveals that the bimonthly Famous Fantastic Mysteries changed format and skipped an issue between its October 1950 release and this January 1951 issue. In 1950 the magazine printed interior illustrations but it wouldn’t resume doing that until later in 1951. So the odds are high that Steele Savage – whose real name was in fact Harry Steele Savage – was commissioned to do an illustration which never ran because of whatever turmoil the changeover occasioned. (The piece itself has no signature, by the way. Was it truly his? The only connection he has to the magazine is that Robert Weinberg attributes the January 1951 cover to Savage, although no one seems to.)

Terence E. Hanley thankfully gives some biography for this otherwise utterly elusive character.

Harry Steele Savage was born on December 21, 1898, in Central Lake, Michigan. According to his biography in The Rainbow Book of Bible Stories, he studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Slade School in London, and in Vienna and Paris. He designed the sets and costumes for Caviar, a musical comedy than ran for twenty performances at the Forrest Theatre in New York in 1934. Savage was also a designer of furniture, and he created at least one poster design during World War II.

Savage was far better known for illustrating Edith Hamilton Mythology, the Iliad, many children’s books about giants and heroes, and sufficient similar fantasy-related items to make him a reasonable choice for a Sax Rohmer piece. On the flip side, he was never known to do any genre pulp or magazine material. (The ISFDB credits him with 22 paperback covers from 1967 to 1971, i.e. after his death in 1970, none of them remotely in his style, although a few are signed as Steele Savage. I don’t believe any are his. Who wouldn’t want a pseudonym of Steele Savage?)

There is absolutely nothing to tie the illustration, or the story, or him to Gnome Press.

Except.

Steele Savage is credited in the ISFDB with one and only one earlier book cover that truly falls into the fantasy genre: The Loves of Lo-Foh, a 1936 tidbit of orientalia by Roswell Williams. The name will click a synapse in deep readers of this website. If it doesn’t, check back to The Porcelain Magician. You will see that Roswell Williams was a pseudonym for Gnome author Frank Owen.

Stop the celebratory dance. Outside of a fantasy version of the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon game, I can’t make this distant connection mean anything. A fantasy-style artist working on a non-Gnome fantasy-style book by one of the 44 Gnome writers is not a significantly greater coincidence than learning that Tom Hanks is a third cousin, four times removed of Abraham Lincoln. They’ve never been invited to the same party.

My guess is that this unused piece of art somehow floated into the hands of someone at Gnome, who decided to slap a generic calendar on the bottom (a style that was everywhere in the early 1950s) and sent it to someone, probably Donald Wollheim, as a private joke to make up for the lack of 1951 Gnome Fantasy Calendar. The lack of explanation of why that someone didn’t write the word Gnome on the calendar makes even that hands-waving guess unsatisfying. Surely a Gnome joke has to mention Gnome.

Yet another inexplicable mystery. A perfect place to end a Gnome article.