Gnome Press started as a two-man operation of Martin Greenberg and David A. Kyle and became Greenberg’s sole property when Kyle left in 1954. Others floated in and out of the business, as full-time or part-time or voluntary assistants or contractors (see The Assistants), and the company had some stockholders for about a year around 1950. Nevertheless, history rightly credits Greenberg and Kyle as the faces behind Gnome.

Martin Greenberg

Martin Greenberg, always known as Marty, was at the center of the science fiction world for more than a decade. Virtually every major name in the field knew him, worked with him, wanted to be published by him. He was sociable and affable, mixing and mingling with fans and pros at conventions and in exclusive sf clubs. He is also somehow a total mystery, with virtually nothing except a few basic facts known about his personal life. Even those are suspect, as few of them can be supported by two independent sources. His memories are often contradicted by the memories of others or contemporary sources, although that is true for almost everything about the era. What I present here are the scrapings of hours of internet searches. This account is of his personal life only. His business activities are given in The History of Gnome Press and in individual title chapters.

Greenberg is listed in respectable sources as having been born in New York City on June 29, 1918, the son of Harry and Sarah Traubner Greenberg.[i] He went to school there but never seems to have attended college. The sf bug captured him early, via the early Hugo Gernsback pulps when he was about nine.[ii] He next turns up in Fort Wayne, IN. In an article titled “The Annals of Hoosier Fandom” in the fanzine Fadeaway #48, April-May 2016, David B. Williams wrote: “Ft. Wayne was a hotbed of SF fan activity in the years just prior to World War II. Two of the local fans, Ted Dikty and Marty Greenberg, went on to become prominent figures in fandom and SF publishing.” The pairing is providential. Besides becoming the leading anthologist in post-war science fiction, Dikty was also one of the founders of Shasta Publishers, a small post-WWII press that vied with Gnome and Greenberg’s anthologies for supremacy. When and why Greenberg went to Fort Wayne is unrecorded, as is when and why he left. He apparently stayed there long enough to be well-known to the fan community.

By 1941, however, he was back in New York where he married Ruth Thaler on October 25, 1941. They would have three children, Harriet, Carole, and Eric.[iii] As many young men would learn, that was not an auspicious date to become a newlywed. Greenberg entered the Army in 1942. Over the next three years he rose to rank of corporal and won five battle stars in the European Theater of Operations.[iv]

After the war he returned to New York and, according to Harry Harrison, became a glazier[v] although Frederik Pohl said he was a glass blower,[vi] also Greenberg’s description. Sometime before the first Gnome Book was published, he moved to 421 Claremont Parkway in The Bronx. The address, probably an apartment complex, is no longer extant, but the street was a nice major road that connected Claremont Park on the west and Crotona Park on the east. (Crotona Park was built on the former giant estate property of the Bathgate family, who also have a street named for them nearby. That neighborhood gave the name to the eponymous hero of Billy Bathgate, the novel by Bronx native E. L. Doctorow.) Greenberg also re-entered fandom. Before the war, fandom was filled with teens, a small and contentious group given to clubs, feuds, and wars of invective through the pages of fanzines. Afterward, the same grouping was older and far less callow. They also tended to have had professional success. Rather than outsiders, gazing wistfully at the pros they desperately wanted to emulate, they were now the insiders. The New York inner core joined together on October 25, 1947 to form the Hydra Club.[vii] Named after the fabled serpent with nine heads, the first meeting of the Hydra Club consisted of nine signatories: Frederik Pohl, Judith Merril, Lester del Rey, Philip Klass (William Tenn), Robert W. Lowndes, Jack Gillespie, David Reiner, David A. Kyle, and Greenberg.[viii]

His name pops up repeatedly in fanzines listing big names at various science fiction conventions, especially worldcons: SFCon in 1954, Clevention in 1955, NyCon II in 1956, chaired by Kyle, where Greenberg was on the committee. Smaller conventions were also part of the duties and fun of a publisher/fan. He attended Philcons regularly and even drove Isaac Asimov to the 1954 Midwestcon in Ohio.

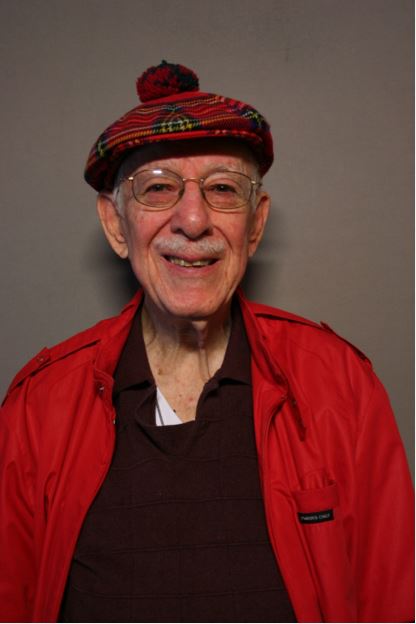

The photo of Greenberg in 1955, found on Men Against the Stars, lends weight to Dave Kyle’s description that “Some people said that with his mustache, if he put on heavy glasses he would look like Groucho Marx, always grinning and full of vim.”[ix] That’s the 1950s You Bet Your Life Groucho, of course, not the movie character. The picture above of him at 90 shows that he kept the look for the next half century.

Greenberg was part of the founding of another major club, the Hyborian Legion, the first Conan fan club. The first meeting took place at the home of George Heap, the President of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society, on November 12, 1955.[x] Officers were: King of Aquilonia, Marty Greenberg; Royal Chancellor, George Heap; Count of Poitain, John D. Clark; Royal Sorcerer, Oswald Train; Royal Chronicler, L. Sprague de Camp; Commander of the Black Dragons, Manny Staub.[xi] Both Clark and de Camp were Greenberg’s collaborators in collecting, editing, and revising all the Conan stories that Gnome had the exclusive franchise for, starting the Robert E. Howard revolution. Train had been the founder of Prime Press, a rival small f&sf press; Staub was a long-term fan who served as the Legion’s representative for decades. The club would spawn a fanzine, Amra, edited by George Scithers, which was to win the Hugo for Best Fanzine in 1964 and 1967 before Scithers became the editor of Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine and won two more Hugos for Best Professional Editor.

Greenberg, therefore, was a joiner, a part of him that remained active even outside f&sf. In the 1950s he moved out to Jericho on Long Island, the next town north of Hicksville, where he maintained the post office box which would be featured on so many Gnome back covers. At some point he became a member of the Knights of Pythias, rising to prelate, or secretary, of his lodge. He also served on the Board of Directors of the Mid-Island Hebrew Day School in Bethpage, just east of Hicksville.[xii] That Greenberg pulled off a move to the New York suburbs indicates that Gnome, for all its troubles, paid him a reasonable middle-class salary, with Jericho somewhat more upscale than Hicksville though nowhere near as staggeringly wealthy as locations along the Long Island coasts. Zillow.com reports that the house was built in 1958, so Greenberg presumably was its first owner. The house is an average, modest suburban home on a mere 1/6 acre plot, but its location means that its estimated value today would be $800,000, low for Jericho.

After Gnome sank under its sea of debt, Greenberg moved through a scattering of jobs, some in publishing, most not. CHALKER says, “he worked as a mainstream editor for Abelard-Schuman, got a degree in art, ran an art shop in a Long Island shopping mall, and wound up the credit manager for a huge metal tubular goods manufacturer.[xiii] He disappeared from the f&sf world for three decades, his reputation thoroughly trashed by his non-payment of authors, but finally began reappearing at conventions in the 1990s. By that time another Martin Greenberg – sometimes but not always using his full name of Martin Harry Greenberg – was deep into his fabulous career as the genre’s – and world’s – primary anthologist, a fiction factory who edited about 1300 anthologies in many genres (although some sources credit him with over 2000). Naturally, the similarity in names between two major science fiction anthologists continues to create endless confusion and is the bane of bibliographers. Martin H. learned to add his middle name from Isaac Asimov, still holding a grudge against Greenberg for his withholding royalty payments. A passage in Asimov’s In Joy Yet Felt is damning:

“The first time I received a letter from him, I responded by asking cautiously if he were the Martin Greenberg who had once owned Gnome Press. When he answered in a very puzzled fashion that he was not, I urged him to use his middle initial, at the very least, if he had one, if he expected to deal fruitfully with the science-fiction world. (Lester del Rey suggested that he change his name altogether, but I thought that was going too far.) From then on, he signed himself Martin H. Greenberg, and I invariably addressed my letters to him, ‘Dear Marty the Other.'”[xiv]

In 2000, Greenberg won the First Fandom Hall of Fame Award, which is given “for contributions to the field of science fiction dating back more than 30 years.” Twenty-one other names connected with Gnome have also won the award over the years: co-founder Dave Kyle; authors Isaac Asimov, Nelson Bond, John W. Campbell, Jr., Arthur C. Clarke, Hal Clement, L. Sprague de Camp, Gordon R. Dickson, James Gunn, Henry Kuttner, Murray Leinster, C. L. Moore, Andre Norton, Frederik Pohl, Robert Silverberg, Clifford D. Simak, E. E. Smith, George O. Smith, and Jack Williamson, artist Edd Cartier; and editorial assistant Algis Budrys.

Martin Greenberg died in Medford, New York, on October 20, 2013.[xv] His Gnome archives were put up to auction a few years later with no takers.[xvi] Somewhere in the world those historically irreplaceable records may still exist.

David A. Kyle

David Ackerman Kyle (1919-2016) (no relation to sf fan legend Forrest J. Ackerman) was an equal partner to Martin Greenberg at Gnome. Greenberg concentrated on acquisitions and marketing; Kyle did everything else, all the dozens of critical backroom jobs that create a working concern. Even so, he is often omitted from the Gnome story or relegated to an afterthought.

Ironic, then, that Greenberg’s personal life outside of Gnome is confined to as few scraps as an obscure pharaoh while Kyle never seems to have had an unchronicled moment. He was everywhere important in the first quarter century of f&sf fandom, in tales told both by outsiders and by himself at lengths of tens of thousands of words. (Quotes here are from Kyle, unless otherwise attributed.) This account is, of necessity, a series of highlights only.

An ancient saying in the genre is that “the Golden Age of science fiction is thirteen,” meaning that kids who have their minds blown by encountering the field in early adolescence fall in love with f&sf deeply and often forever. Kyle believed in that adage so fervently that he got his age wrong in his own memoirs. In the spring of 1933, an older friend who lived across the street from his family in Monticello, NY, gave him an old copy of the first issue of Hugo Gernsbeck’s Science Wonder Stories, the issue that introduced the term “science fiction.” Kyle gives his age as thirteen, but he was just past his fourteenth birthday then.[xvii] The event “changed his life.” Primitive as those stories appear to us today, they were a leap of sophistication higher than the Buck Rogers radio show Kyle was a fan of. He bought every issue of the magazine, by then renamed Wonder Stories.

Gernsback had a fortunate obsession with letter columns, striving to give the young fans a national meeting place abetted by the fan groups he organized. Kyle had his first letter to Wonder published in June 1934.[xviii] Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon comics remained almost as big an influence. A budding cartoonist, Kyle’s first fanzine, 1935’s Fantasy World, consisted almost entirely of sf comic strips, the first such fanzine.[xix] The next year would be momentous enough just for the 17-year-old Kyle graduating high school, being forced through lack of funds to decline his acceptance at Dartmouth, and moving to New York to attend the Art Career School instead.[xx] Yet a slew of more firsts swelled the importance of that critical 1936: he was part of the formation of FAPA, the Fantasy Amateur Press Association, founded the (short-lived) Phantasy Legion, was one of the dozen or so attendees at the first science fiction convention, and sold his first story, “Golden Nemesis,” to Hugo Gernsback. Unfortunately, 1936 was also the year that Gernsback lost control of Wonder Stories. The new editor sent the completely typeset and illustrated story back, which sat for five years until Kyle’s Futurian friend Donald Wollheim gave it fleeting life in the forgettable Stirring Science Stories.[xxi]

In the meanwhile, Kyle made friends with everyone in east coast fandom, including fellow Art Career School student John R. Forte, Jr. (see The Artists), went back to Monticello to work in his family’s print shop (foreshadowing alert), entered the University of Alabama in 1938, became a member in absentia of the Futurians, the seminal New York fan club that spawned dozens of professionals and an almost equal number of marriages, and returned to New York sans degree.[xxii] The Futurians also edited many of the low-end f&sf magazines in the early 1940s, to which Kyle contributed illustrations. Sharing a cold-water flat in New York with future Nebula Award-winning writer Richard Wilson, “the five bucks cash I would receive for pay-on-delivery artwork kept us in potatoes and oatmeal.” Though that five bucks “could last a week, even in New York,”[xxiii] he went peripatetic again, back to Monticello where he helped his family start a daily newspaper for which he wrote a column titled “Tomorrow Must Come” as managing editor.[xxiv]

Pearl Harbor interrupted the small-town life and Kyle joined the Army shortly after. A stint in Officer Candidate School made him a second lieutenant in the Army Air Force. He was a captain when the war ended, but stayed in the Reserves and retired as a lieutenant colonel in the 1950s.[xxv] His first stop after the war was to go back to his home-town newspaper, but Monticello couldn’t hold him. Within a year he gravitated again to New York, where he swiftly immersed himself in the f&sf world while studying under the GI Bill at Columbia University. He met Marty Greenberg, and with him put his name down as one of the nine founders of the ubiquitous Hydra Club, as told above. The fortuitous pairing led to the beginning of the Gnome Press. Kyle printed Gnome’s first two books on his family’s press.[xxvi]

With all the hats he wore, it feels like being a hardcore, inner-circle fan was as or more important than any other. The entire period he was with Gnome he appeared in fanzines, attended all the worldcons and many lesser cons, and spent much of his off-time with other fans.

One of his many escapades occurred in 1949 at Cinvention, the Cincinnati Worldcon. Under another of his infinite number of hats, Kyle supplemented his hours at Gnome with work at a national wire-service, Transradio Press.[xxvii] The Toronto Worldcon in 1948 had received especially nasty teasing in the news. A mild comment by Kyle that sf had dealt with atomic bombs long before Hiroshima was headlined “ZAP! ZAP!/ATOMIC RAY/IS PASSE/WITH FIENDS!”[xxviii] Determined to give the next convention better press, he arranged a series of events that included a live television broadcast featuring Kyle, Fritz Leiber, Jr., E.E. Evans, Judy Merril, E.E. Smith, Jack Williamson, Hannes Bok, John Grossman, Forrest Ackerman, Ted Carnell, Bob Tucker, Mel Korshak, Lloyd Eshbach, James A. Williams, and Dr. C. L. Barrett, a terrific assembly of authors, publishers, fans, and artists giving a serious look at the genre.[xxix]

Unfortunately, Kyle also arranged for the photographers to be given a free hand with the hall costumes. He brought along his girlfriend, Lois Jean Miles, a professional model described by his friends as a “beautiful, blue-eyed blonde who deserves better.”[xxx] Mixing business with pleasure, as was the norm for f&sf, Miles became the Hydra Club’s secretary when Kyle was named chair. The intermixing of the Hydra Club and Gnome is seldom better illustrated than discovering that Miles “brought with her two friends who subsequently became regulars at Hydra, Carol and Edna. Carol became Fred Pohl’s wife after Judy Merril, and Eddie became Mrs. A.J. Budrys.”[xxxi] In Cincinnati, struggling to remain upright because of a radio receiver implanted into her upswept hair, “Miss Science Fiction,” as Miles was billed, wore only a leopard-skin bra and a hip-length skirt.[xxxii] The talking heads were ignored for the cheesecake. “Vampires, mad scientists, spaceship captains and other oddities of folklore and futurism,” snarked the caption over the pictures in the Cincinnati Enquirer.[xxxiii] Other fans were so incensed at the east coast antics that Portland won the bid for the next year’s Worldcon over the favored New York. Miles similarly spurned Kyle; the next year she married Futurian and first Worldcon veteran Jack Gillespie.[xxxiv]

By around 1954, though, after taking a degree in English from Columbia University in 1951, Kyle had slowly phased out of his responsibilities at Gnome to launch yet another new career. He and his father built and operated a radio station in Potsdam, New York, up near the Canadian border. The 350-mile trip to New York in that era before interstates must have been extremely tiresome but he kept his old cold-water flat there for his periodic returns for fan gatherings.[xxxv] It also made for a jumping-off point for trips to conventions with other New York fans, such as the otherwise unremarkable 1955 Worldcon, Clevention in Cleveland, another event that would change his life.

Ruth Landis, a minister’s daughter from New Jersey, read about Clevention in Astounding Science Fiction. She made the unusual decision for the time to attend by herself, not knowing a single person in the field. Kyle didn’t notice her but his friends did. “Upstairs, in the convention suite, there’s a very pretty young girl sitting alone. Get cracking!”[xxxvi] He did. They sat together at the Hugo Awards banquet and reconnected the next year when she became part of the New York fan scene.

New York had finally won the right to host another Worldcon, its second, and somehow Kyle, despite living 350 miles away, became its chair. Landis officially became secretary to NyCon II. Running a convention, a multi-day event for over a thousand people with an all-volunteer committee, is a logistical nightmare. Kyle left his job to spend the last two months working full-time in New York. His romance with Landis “blossomed” and they married in 1957.[xxxvii]

They had perhaps the archetypal sf fan honeymoon. London won the bid for that year’s Worldcon, the first time it was held outside North America. Kyle chartered an airplane to fly the elite fans and professionals, i.e., his closest friends, to England, an eye-popping gesture in an era when many fans had in 1956 complained about the 50% increase for membership in NYCon II – from $2 to $3. “This is still a great story to tell,” Kyle wrote later, “that we had 53 people along with us on our honeymoon. The topper is that that my parents went, too!”[xxxviii] By some feat of synchronicity, the marriage lasted 53 years, until Landis’ death in January 2011. They had two children, Arthur (“AC”) and Kerry. (see also The Assistants)

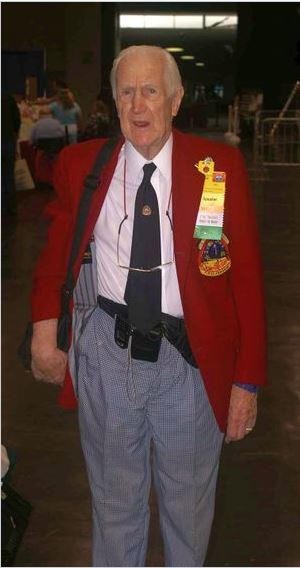

The Kyles moved to England in 1970. While there a British publisher doing a series of Pictorial Histories asked him to do one on f&sf. A Pictorial History of Science Fiction was published in 1976 and sold 75,000 copies. A 1977 follow-up, The Illustrated Book of Science Fiction Ideas and Dreams, tanked because, as Kyle told it, the publisher gave it a look so similar to the first book that people didn’t realize it was a new volume.[xxxix] Kyle kept attending Worldcons until he reached the age of 90, when the more distant ones proved too daunting. At the time he had attended more than anyone else in the field. Over those late years he received a pageful of honors from the fan community. He was made a member of the First Fandom Hall of Fame in 1988. An even higher honor was bestowed upon him posthumously. The Big Heart Award embodies, as one recipient noted, “good work and great spirit.”[xl] Named after early fan E. E. Evans, the Big Heart was given to Kyle in 1973. He took over the administration of it in 2000. In 2018, it was re-named the David A. Kyle Big Heart Award.[xli] No more needs to be said about the reverence fans had for the “man in the red jacket.”

[i] Martin Greenberg bio, Who’s Who in Commerce and Industry, Volume 14, 1965.

[ii] “Martin Greenberg: The Last Gnome!” interview by Christopher M. O’Brien, Filmfax Plus, Summer 2014, 65.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] “Publisher Martin Greenberg’s death announced,” https://www.sfscope.com/2014/02/publisher-martin-greenbergs-death-announced/.

[v] Harry Harrison, Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!: A Memoir (New York: Tor Books, 2014), 79.

[vi] Frederik Pohl, The Way the Future Was (New York: Del Rey Books, 1979), 168.

[vii] Lloyd Eshbach, Over My Shoulder (Philadelphia: Oswald Train: Publisher, 1983), 285.

[viii] Dave Kyle, “The Legendary Hydra Club” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m25/kyle.htm.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Lee A. Breakiron, The Nemedian Chronicles #2, 1.

[xi] The Fine Books Company, https://www.vialibri.net/searches/202008052115Bi83W4DvR.

[xii] Martin Greenberg bio, Who’s Who in Commerce and Industry, Volume 14, 1965.

[xiii] Publisher Martin Greenberg’s death announced, https://www.sfscope.com/2014/02/publisher-martin-greenbergs-death-announced/.

[xiv] Isaac Asimov, In Joy Yet Felt (New York: Doubleday, 1980), 758.

[xv] Jack L. Chalker and Mark Owings, The Science-Fantasy Publishers (Westminster, MD: The Mirage Press, 1991), 207.

[xvi] “Important Gnome Press Archive/,” https://www.auctionzip.com/auction-lot/Important-Gnome-Press-Archive_43A4C41BE9.

[xvii] Dave Kyle, “Those Wonderful Turbulent Thirties,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m19/kyle.htm.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Dave Kyle, “Farewell, Teens, Farewell,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m20/kyle.htm.

[xxi] Dave Kyle, “A Hugo Gernsback Author,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m07/kyle.htm.

[xxii] Dave Kyle, “Farewell, Teens, Farewell,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m20/kyle.htm.

[xxiii] Dave Kyle, “Rocketships Came Later,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m26/kyle.htm.

[xxiv] Mary Ann Ebner, “Science-Fiction Pioneer Is a Habitue of Cold Spring,” https://highlandscurrent.org/2012/07/20/science-fiction-pioneer-david-kyle-is-a-habitue-of-cold-spring/.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Dave Kyle, “Rocketships Came Later,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m26/kyle.htm.

[xxvii] Fred Patten, “The 7th World Science Fiction Convention,” https://www.cfg.org/history/cinvention/cinvention.htm.

[xxviii] Leslie A. Croutch, “TORCON MEMORIES: The 1948 World Convention” WCSFAzine Issue # 11, July 2008, 20.

[xxix] Patten.

[xxx] Dave Kyle, “Sex in Fandom,” http://www.jophan.org/mimosa/m10/kyle.htm.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] “When Fantasy Fans Met,” Cincinnati Enquirer Pictorial Magazine, September 18, 1949, 16.

[xxxiv] Kyle, “Sex in Fandom”.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Ibid.

[xxxvii] Ibid.

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Michael A. Banks, “David A. Kyle: From the Glorious Past Through the Far Future of Science Fiction & Fandom,” Starlog Magazine, June 1981.

[xl] “Big Heart Award,” http://fancyclopedia.org/Big_Heart_Award.

[xli] Ibid.