Gnome was always referred to as a two-man firm, with Marty Greenberg and Dave Kyle partnering to do all the work. That can’t be true. Check any period film and you see that even the poorest, cash-strapped, whisky-soaked private eye managed to have a secretary in the front office, if for no other reason than to answer the phones when he’s out on a case or a bender.

Gnome must have had one as well, especially when Greenberg took the 11th St. office. Even Frederik Pohl’s one-man agency in the same building had a secretary until almost the end. Greenberg makes one reference to a secretary, someone hired after Kyle left the company, who had the habit of leaving at three o’clock when Greenberg was out on the road. Greenberg referred to him as “he,” certainly an oddity for the era. One other oddity. The examples of Greenberg’s letters I’ve seen don’t appear to have been written by a professional typist, as a secretary certainly should have been.

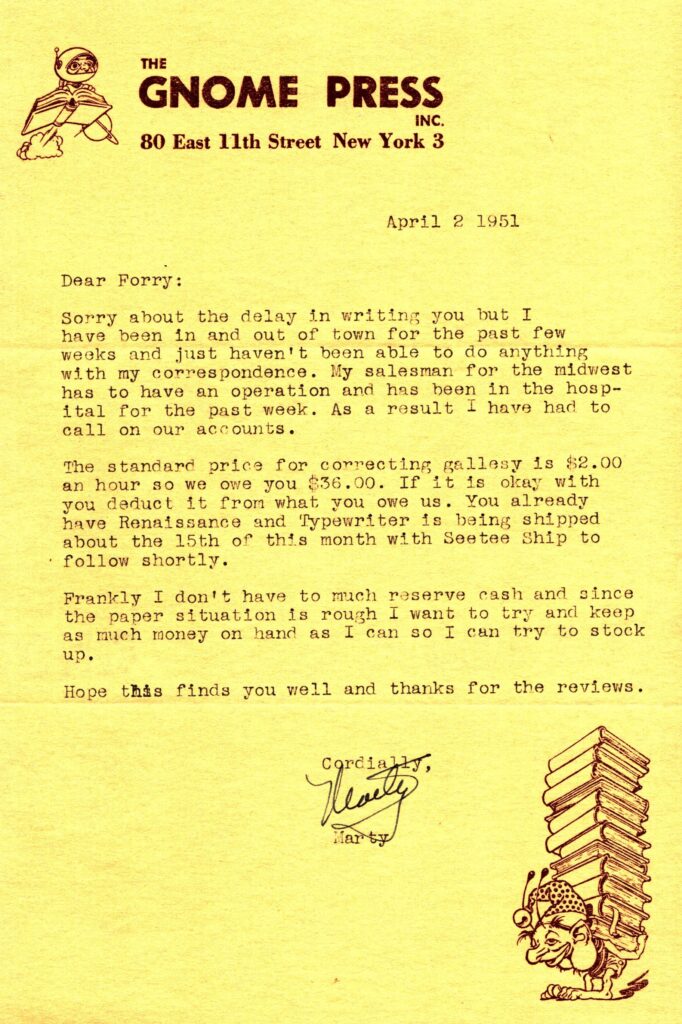

Moreover, businesses need outside experts. In his memoir, In Memory Yet Green, Isaac Asimov throws away this line: “Also in the car was Marty’s accountant, a very nice fellow who must have had difficulty remaining sane if he seriously tried to handle Marty’s books.” Forrest J. Ackerman, fan, writer, agent, dealer, and collector/historian of f&sf, corrected galley proofs from his home in California and it would be surprising if others didn’t fill that role over the years.

— From my personal collection

Gnome was a private corporation, which implies stockholders. They also existed starting in 1950. From what little we know, they played no part in the business except to demand money.

None of these mostly anonymous adjuncts to the core business of acquiring and selling fiction are what I mean as assistants. I’m limited that title to those few who handled the manuscripts themselves and so made their marks on the products that went out to the eager readers of the f&sf that Gnome sold.

With Kyle attending classes at Columbia and slowly phasing his way out of the business, Greenberg started hiring editorial assistants to do various chores around the office and handle some of the editing and copyediting. Algys Budrys was the first, starting in late 1952. As did everyone who encountered Greenberg, he left behind a head-shaking anecdote, told in ESHBACH.

I was supposed to open the shop at 9:00 every day, with Marty coming in toward noon, but he wouldn’t give me a key, always promising that starting tomorrow he’d be there on time. Fortunately, the very first day I found myself pacing those long and ugly narrow halls with nothing to do, I discovered that the key to the front door of Jerry Bixby’s [f&sf writer and editor Jerome Bixby, who would collaborate with Budrys in 1953] Brooklyn apartment house, if put halfway into the Gnome Press lock and jiggled, would do the trick. Marty then pointed out that obviously I didn’t need an official key. He also demonstrated thereafter that he didn’t need to come in before noon, either.

Budrys didn’t last long, sliding over to a similar position at Galaxy in 1953. Greenberg turned to another Columbia student, Joseph Wrzos (pronounced like Ross). Wrzos left us the most complete description of what it was like to work at Gnome. Packing book orders was basic to the scut work he did around the office but as he grew into the role it graduated into “reading the slush pile, editing accepted manuscripts, doing dust-jacket blurbs, and even … working with artists.” (see The History of Gnome Press) One of the major perks of the job was interacting with the artists and writers who wandered in to talk to the boss. Behind in his work, Greenberg blew off a lunch date with Arthur C. Clarke and Wrzos snagged a long voluble talk with the visiting Brit. He glowed when Clarke praised the flap copy put on Against the Fall of Night, since it was his writing.

Meeting authors didn’t pay the bills and Wrzos stayed only until 1954. ESHBACH says “he became a librarian at Rutgers University,” but he evidently conflated Wrzos’ undergraduate college with a job at a New Jersey high school. Weirdly, Wrzos later wrote that he never met Kyle in person.

Ruth Landis, who would become Kyle’s wife in 1957, had the position for a short time before their marriage. No other names have been mentioned to fill in the gaps.

We know that Greenberg turned to others in the f&sf community to do jobs. Andre Norton spent several years (the exact number varies from source to source) as a first reader from her home, and literally from her bed, in Cleveland. (see The History of Gnome Press) She was also the Editorial Director of the short-lived Gnome Juniors program and made editorial suggestions that were usually adhered to. (see The Forgotten Planet) Doing business by mail must have suited Greenberg better than going to the office. Around 1956, Chicago fan Earl Terry Kemp set the type for “Gnome Press ephemera. Book lists, advertising copy, newsletters, dustjacket back cover and flap text, all the usual. Larry Shaw wrote the copy and I set it into type.” Larry Shaw was also a long-time fan turned editor, who was running Infinity Science Fiction at the time. Kemp didn’t know whether Shaw received any payment for his work. Kemp himself did the typesetting for free copies of new Gnome releases.

The early books were all designed by Kyle. A few names pop up later: Sidney Solomon for Mel Oliver and Space Rover on Mars, Betty Kormusis on The Forgotten Planet, Robin Fox on The Philosophical Corps. W. I. van der Poel, Jr. became the uncredited art director around 1956, so it’s likely that he did the design work as well, but his name is never mentioned as a designer, although he was credited with many covers. (see The Cover Artists G-W)

Short biographies of the three Assistant Editors and Norton are given below.

Algis Budrys

Algirdas Jonas “A.J.” Budrys (1931-2008) is almost certainly the only f&sf writer born in Königsberg, East Prussia, Free State of Prussia, Germany. He wasn’t truly a native German: his father was the Counsel-General for Lithuania there and, after 1936, for the United States, where AJ, as he was known, grew up. Lithuania disappeared as a country during WWII making him stateless. His ambivalent status was reflected in much of his later fiction.

Budrys claimed that he taught himself English by reading Flash Gordon and other comics in the Sunday newspaper. A neighbor who ran a general store gave him unsold science fiction magazines turning him, at the age of 11, into a lifelong fan of the field. He entered the University of Miami at 16, dropped out and later re-enrolled at Columbia University, though he does not appear to have taken a degree. In New York Budrys connected with the thriving f&sf community. He became an Assistant Editor at Gnome in 1952 and in 1953 took a similar position with Horace Gold at Galaxy Science Fiction. At virtually the same time his first stories appeared simultaneously in two different November 1952 magazines.

After he married Edna Duna in 1954, he wrote furiously under his own name and a large selection of pseudonyms. Two classic novels emerged from that effort, Who? (1958) and Rogue Moon (1960). Unfortunately, he hit his high point just as the field was hitting a low. Finances required him to leave the genre for other jobs in publishing and advertising. Only a handful of fiction in the genre appeared over the rest of his life but his name appeared everywhere as he became known as one of the field’s premiere reviewers and essayists. He launched and edited Tomorrow Science Fiction from 1993-1997 and before and after edited the Writers of the Future anthologies.

Budrys was a 2007 recipient of the Pilgrim Award, presented by the Science Fiction Research Association for lifetime achievement in the field of science fiction scholarship. He posthumously received the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America Solstice Award for life achievement in 2009.

Ruth Landis

Ruth Evelyn Landis (1930-2011) was a minister’s daughter. After high school, she moved to New York and took the usual variety of jobs, including working as an analyst for a public opinion research firm and as an electrocardiogram technician.

In 1955, after reading about the event in Astounding, she made the then unusual decision to go by herself to the Clevention Worldcon in Cleveland, unusual because she knew nobody in fandom and single woman were rare at such events. There she met Dave Kyle and was eager to start seeing him again the next year when she commuted from Princeton (for yet another job) to attend meetings of the thriving New York fan community and he made the occasional long trip from upstate Potsdam to be with his friends. Kyle somehow became chair of the 1956 Worldcon, NyCon II, and he asked Landis to be secretary. The rest of the story is told in The Founders.

All but one bit of it. ESHBASH wrote that “By the time the convention ended Ruth and Dave were engaged to be married, and Dave arranged for her to work at Gnome Press with Marty.” Kyle himself, who wrote copiously about his fan days and his fannish marriage and honeymoon, apparently never talked about the seemingly significant connection to his old firm except for a passing “and Ruth Landis was there.” ESHBACH also said that Landis was “from Pennsylvania,” an assertion I cannot find any independent evidence for, whether it means that she was born in Pennsylvania or just happened to be living in Pennsylvania at the time or was simply a mistake.

The Kyles had two children, Arthur (“AC”) and Kerry, and moved to London in 1970. Keith Freeman remembered that, “Their parties became legend – with Ruth spending an inordinate amount of time slaving over a hot stove… breakfast (dollar pancakes and a contest to see who could eat the most), lunch and dinner – a never-failing supply of delicious food. And yet even with this Ruth joined in all the fun and games and was a fantastic hostess.” And at Christmas, “The turkey (usually the largest her butcher had) would go in on Christmas Eve and one would wake with the whole house filled with the aroma of roast turkey, with AC and Kerry rushing around to see if they could find an adult awake enough to let them get at their presents. The weary tones would come from Ruth, ‘Go back to sleep, we were up until all hours getting the bird ready and watching a lousy film on the TV that David wanted to see…’”

Bill Burns added, “Not long after, the Kyles bought a rather run-down property nearby. The house and grounds needed a lot of work – but what a location, with the house situated on the south bank of the Thames, and a tributary running along one side of the garden. The first parties at ‘Two Rivers’ were often day-long working events, with fans pitching in to help get the house and garden in shape, and the visitors’ book was eventually filled with the names of British and American fans.”

Landis enthusiastically accompanied her husband to conventions all over the world, not an easy task from “Skylee,” their home in Potsdam, New York, a small city near the Canadian border. Rather than running around convention halls after her peripatetic husband, Landis started making and selling elaborately decorated fantasy eggs. She was an active participant in the fannish life until the end.

Andre Norton

Alice Mary Norton (1912-2005) was seventeen years younger than her older sister and so grew up almost as an only child, one whose parents encouraged her love of books. She visited the public library weekly, received books as rewards for good grades, and was read to by her mother as she did her chores. Norton became literary editor of her high school newspaper and wrote her first novel in free time at school, although it wasn’t published until she was 28. She later reminisced, “To me, the sense of wonder means that a book becomes so alive to someone that they remember it for a long time afterwards. I remember experiencing it when I first read The Face In The Abyss by A. Merritt. I would buy Thrilling Wonder Stories, Planet Stories, Amazing Stories, Astounding Stories, and others. This was in the days when one had to hide these types of magazines, because they were considered by some to be so trashy that a person would not want to be seen in public with them. Some of my favorite writers of that era were Eric Frank Russell, Edmond Hamilton, Leigh Brackett, C. L. Moore, and others.”

She started college at her hometown Western Reserve University but had to drop out in her freshman year, landing a job as a children’s librarian at the Cleveland Public Library. She claimed to have worked at 38 of its 40 branches before she left in 1950, or 1951, or 1952 depending upon source. The lack of a degree kept her from advancing higher in the system, but didn’t dissuade the Library of Congress from hiring her in 1940 as a special librarian for a project on a project related to alien citizenship. That halted because of the war, and for a short period of time she owned and managed a bookstore and lending library called the Mystery House, situated in Mount Ranier, Maryland. It quickly failed and she went back to the Cleveland Library.

Norton continued to write while working. She published her first novel, The Prince Commands, being sundry adventures of Michael Karl, sometime crown prince & pretender to the throne of Morvania, in 1934 under the pseudonym of Andre Norton. She would say that publishers demanded a masculine name to sell boy’s books, but she legally changed her name to Andre Norton that same year so perhaps something more was involved. The director of “work with children” at the library wrote a description of her in what seems to be a letter of recommendation to the publisher Houghton-Mifflin in 1935.

Miss Norton is difficult to describe. She is only 23 but looks at least 30. She has a great deal of poise and reserve but is at the same time alert and keen to situations. Her speech is very formal, sometimes the children are amazed by her long words, but she writes wild tales with quickness and ease. Her imagination seems well directed, however. She is studious and has read everything available in the Cleveland Public Library that relates to her subject. She already has quite a bibliography. … I think her contribution, if any, will be in the Rider Haggard type of fiction or new pseudo-scientific fields.

Five similar novels appeared before she published her first science fiction book, Star Man’s Son, 2250 A.D, in 1952. She might have had a very different career if Marvel Tales hadn’t gone out of business in 1935 before publishing her story “The People of the Crater.” The same editor published it in his Fantasy Book in 1947, under the pseudo-pseudonym Andrew North. Apparently the experience rewhetted her appetite for f&sf, because more Andrew North stories appeared before she wrote two books under that name for Gnome (and a third later).

A bad case of vertigo forced an end to her library career, but even often confined to bed she merely became busier. She started by editing anthologies until she established herself as a major writer of YA fiction, first mostly science fiction and later mostly fantasy, notably the Witch World series, although non-genre books continued to appear occasionally. Adoring fans continued to read and demand her novels as adults and her books were marketed as such while retaining a younger audience. Her career is as legendary as any of the other names in this book.

Syracuse University has some of her papers, and summarized her many recognitions in the field on its website.

She was the first woman to be a Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) Grand Master and to be inducted in the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. She received Skylark, Balrog, and World Fantasy awards, and was the first woman to win the Gandalf Grand Master of Fantasy award. She was a member of the Women’s National Book Association, Theta Sigma Phi, and encouraged beginning writers with “High Hallack,” a retreat and research library for writers which she opened and ran from 1999-2004. The SFWA named an award in her honor, the Andre Norton Award for young adult novels, first given in 2006.

Joe Wrzos

Joseph Henry Wrzos (1929-2023) was a cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Rutgers University when he started graduate school at Columbia University. Coming to the big, bad city apparently corrupted him, because in 1953 he became Gnome’s Assistant Editor.

Bright and bookish, he then spent a year as a high school librarian but switched over to high school English teacher, eventually becoming the chairman of the Millburn, NJ, Senior High School English Department.

Nobody ever seems to fully leave f&sf once immersed in it. Sol Cohen hired him to replace Cele Goldsmith as editor of Amazing Stories and Fantastic in 1965. It says a lot about the field that during Goldsmith’s legendary stint as editor, when she discovered almost as many top names as John W. Campbell, circulation declined to under 35,000. Cohen bought the fading magazines and wanted to go cheap by turning them into all reprint from Amazing’s depth of back issues. Running stories from the 1920s and 1930s immediately boosted circulation by 40%. Wrzos (who anglicized his name as Joseph Ross in the magazines) tried to keep some connection to modern f&sf and convinced Cohen to run a new story every issue, producing some fine new fiction that way during his two-year tenure.

He continued to be active in fandom and in publishing, especially in fantasy, with a series of titles. He ghost-edited In Lovecraft’s Shadow: The Cthulhu Mythos Stories of August Derleth (1998) and Derleth’s posthumous anthology New Horizons: Yesterday’s Portraits of Tomorrow (1998); co-edited August W. Derleth (1909-1971): A Bibliographical Checklist of His Works (1996) and Seabury Quinn’s Night Creatures (2003);and, most recently, edited Hannes Bok: A Life in Illustration (2012). Wrzos received the Sam Moskowitz Archive Award in 2009 and was made a member of the First Fandom Hall of Fame in 2016. He wrote a letter to Black Infinity magazine in 2019, the last mention of his activity I can find.

His second wife was Helen De La Ree, sister of longtime fan turned collector, publisher, and historian Gerry De La Ree. There’s always a fan connection. Helen also worked on projects like In Lovecraft’s Shadow.