Comments

Frederik Pohl (1919-2013) was only 35 when Undersea Quest appeared but he had co-founded the New York science fiction society that was the epicenter of fandom, married two of its members, edited multiple sf magazines as a teenager and followed those with multiple reprint anthologies, created the first original anthology series in the field, collaborated with Isaac Asimov and Judith Merril, and topped all that by blanketing the field in 1953 and 1954 with stories that would be among the most famous of any published in the 1950s. He also spent a few years after the war as the agent for many of the biggest names in the field, selling many of their books to Marty Greenberg, who conveniently had his office in the same building.

Pohl vowed to run a completely ethical agency, not the norm for the field. Rather than hide royalties from his authors, he made a point of fronting them complete payment before they even turned in their work. Pohl was as smart as any name on this website, a collection including some bona fide geniuses, yet this decision is jawdropping. Amazingly it worked exactly as he had planned. His writers did not have to give in to the temptation to write what they thought editors might like: they wrote for themselves, and wrote better stories. In a short time, he was furnishing half the wordage at Galaxy. In a slightly longer time, his checks were bouncing. By 1953, the agency was profitable only because he had laid off all his employees and did every job himself, a killing pace. And he was $30,000 in the hole. Besides, he badly wanted to write his own stories. He closed his agency and plunged into writing full time.

Having two writers collaborate is a spectrum that ranges from nightmare to group mind. As I relate elsewhere, Catherine Moore and Henry Kuttner could finish each other’s sentences. When Pohl tried it with Lester del Rey “the whole exercise took twice as long a it should have, with ten times the trouble.” Pohl was a natural collaborator, though, He worked with two dozen other writers over the course of his career, and was the only person in f&sf ever to collaborate with William Morrison, the Gnome author of Mel Oliver and Space Rover on Mars. Pohl’s books with C. M. Kornbluth created the subgenre of sociological science fiction, a bombshell in the 1950s. Jack Williamson was not as close a friend as Kornbluth, but was going through a down period in the 1950s. His needs and Pohl’s meshed perfectly.

Actually, I rather like taking someone else’s draft and making it publishable. The nine or so books that I wrote with Jack Williamson were done more or less that way. The first of them, Undersea Fleet [sic], he gave to me as a jumble of notes and scenes. He had worked over the material a dozen different ways without ever having it jell into a novel, so he turned it over to me to get a fresh view on it.

They wrote two more books in the series, Undersea Fleet and Undersea City. To the despair of later collectors, the books were issued in reverse alphabetical order.

Gnome notes

Every merchant needs a sure body of repeat customers to cover costs. For science fiction publishers in the 1950s, that turned out to be library sales. Now that books were available in hardback and were reviewed in mainstream publications, librarians saw science fiction as part of the fiction market that drew patrons. The symbiosis worked to serve both sides’ needs.

Young adult books traditionally sold better to libraries than to bookstores. Young fans seldom had the money for hardbacks and for whatever reasons “juveniles” seldom were issued in paperbacks, even though paperbacks were more accessible to young readers than hardbacks. Libraries breached that gap.

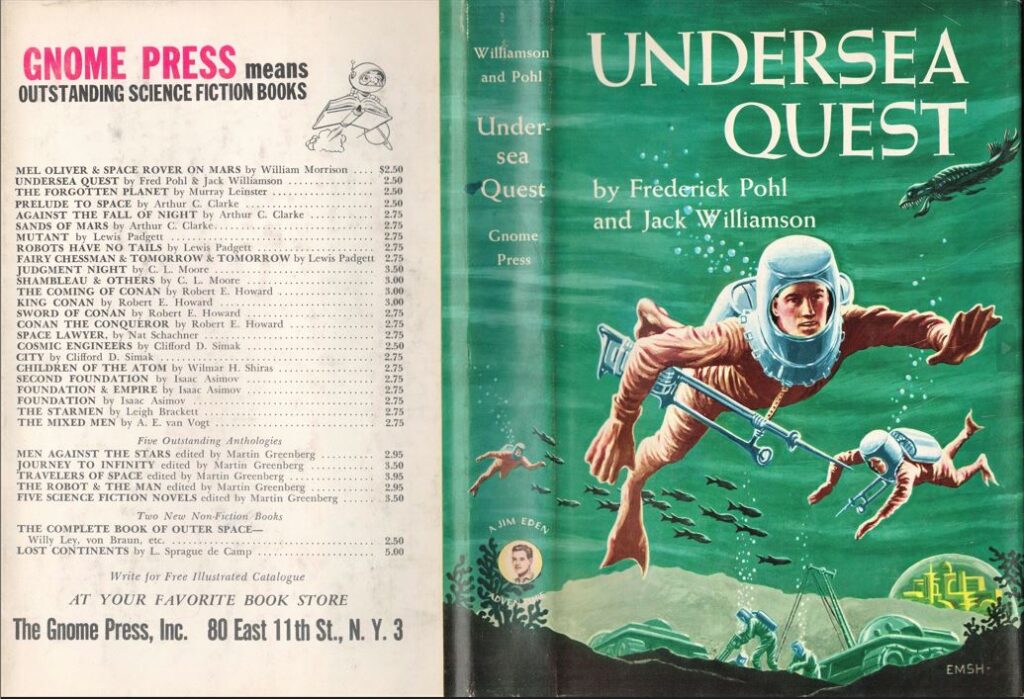

Quest had the same note about Gnome Juniors on its rear flap that The Forgotten Planet did, including the credit to Andre Norton. Yet, while Gnome released five more YA books, Gnome Juniors were never mentioned again, even on Norton’s own junior fiction for Gnome. Norton probably stopped working for Greenberg at about this time, which might have created an ethical objection to him using her imprimatur. Or maybe the fiasco over Forgotten’s “beetle” cover tainted the name and Quest’s flap copy was already in print. Either way, it looks in hindsight to be a lost opportunity.

Pohl was certainly known to every person in the world of science fiction. Anybody with the most casual acquaintance with the field should have caught a misspelling and corrected it instantly. Yet the dust jacket cover typos Frederik as “Frederick.”

Reviews

John S. Harris, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 15, 1955

[Books] like “Undersea Quest” can certainly be considered present-day counterparts of the Tom Swift series. As such, they not only allow gratification of the youngster’s love of adventure, but stimulate his imagination with the possibilities of things beyond the present and known.

Villiers Gerson, Amazing Stories, September 1955

“Undersea Quest” is as good as it sets out to be – a simple, pleasant juvenile which should give teen-agers an engaging brace of hours away from the television set.

Contents and previous publication

• Chapters 1-21 (original to this volume).

Bibliographic information

Undersea Quest, by Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson, copyright registration date 25Nov54, Library of Congress catalog card no. 54-7256, title #45, back panel #26, 1954, 189 pages, $2.50. 5000 copies printed. Hardback, light green cloth, spine lettered in maroon. Jacket design by Emsh. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Manufactured in the U.S.A. Composition by Slugs Composition Co., New York. Printing & Binding by H. Wolff Book Mfg. Company. Back panel: 31 titles. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

Variants

None known.

Images