Comments

Howard published seventeen Conan stories in Weird Tales from 1932-1936; L. Sprague de Camp missed them all. Many years later he told Lin Carter that he had somehow gotten the notion that Weird Tales published only ghost stories, a genre not to his liking.

The two were brought together – tiny world alert – by Gnome. De Camp’s writing partner Fletcher Pratt received a reviewer’s copy of Conan the Conqueror and handed it off to his friend. De Camp had, at the age of 43, the same reaction legions of teen-age boys have over the decades had to Conan and Doc Smith and Tolkien and Heinlein and so many more f&sf legends, a lightning bolt to a brain lobe that flashed an unscratchable itch of “I want more!” Pratt hated Conan and slagged it in the august pages of the New York Times Book Review. Whereas de Camp’s review, appearing in Astounding, displayed some critical faculties but was mostly a fan letter, ending with “A must for those who – like your reviewer – revel in a sanguinary combination of sorcery, skulduggery, and swordplay.”

As an adult and legend in his own right, de Camp had resources that teen-age boys couldn’t dream of. In The Sword of Conan comments, I recounted how Oscar J. Friend, the agent for the Howard estate, had “reworked” an unpublished Howard story and sold it to Donald Wollheim for his Avon Fantasy Book anthology series. Most fans didn’t have casual conversations with Wollheim, but de Camp could and did. Long before the story saw print, de Camp not only heard of its existence but that Friend had a trunk full of Howard manuscripts which he had never had time to carefully examine. Again, de Camp could do something beyond the reach of any ordinary reader. He knew Friend and his phone number and immediately called him up. On November 30, 1951, still before the story’s public appearance, de Camp met with Friend and was given about twenty pounds of manuscripts, the equivalent of some 2,000 pages of material.

When de Camp sifted through them page by page, he spotted three Conan manuscripts, one major. “The Black Stranger” was a long yarn about Conan and pirates, both normally Howard’s forte. When it nevertheless failed to sell, Howard rewrote it as a straightforward pirate tale as “Swords of the Red Brotherhood” and still couldn’t move it.

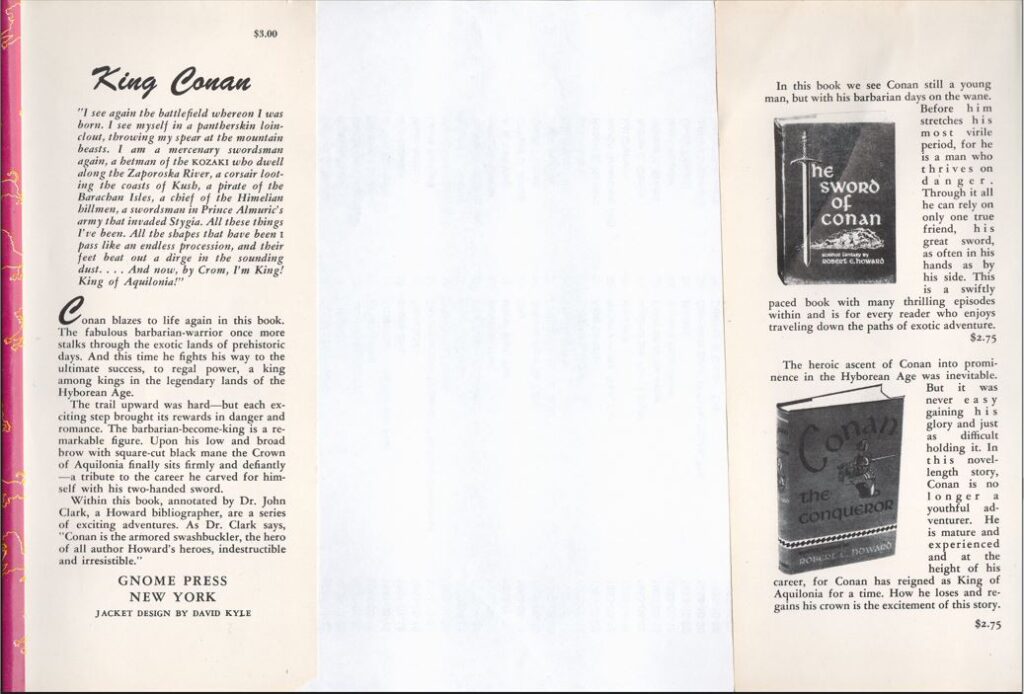

The work of this suave, erudite, cultured author of light, humorous adventures of professors appeared at first glance to be antipodal to Howard’s crude, violent, and ill-told tales. Nevertheless, de Camp had such an intense conversion moment that immediately after his introduction to Howard he wrote what was essentially Howard fan fiction, although, being de Camp, he could sell it professionally. Three adventures set in the Pusâdian Age, Howard with the initials filed off, appeared in 1951, all before his meeting with Friend. Thus primed with the style and texture of a Conan tale, de Camp rewrote and streamlined “The Black Stranger” and sold it to Fantasy Magazine under Howard’s original title. Fantasy’s editor, Lester del Rey, added a breathless half-page preface. The title got changed to “The Treasure of Tranicos” for inclusion in King, to limit confusion to other Conan stories with “Black” in the title.

Did it work? In his review of King Conan, P. Schuyler Miller gave what might be the ultimate insight into Howard’s captivating writing.

I’ve convinced myself that the reason Howard was able to make the preposterous doings of his superhuman hero so real was that he believed in him completely, and projected himself into the Cimmerian’s personality. Anachronisms, contradictions, impossibilities, absurdities of all kinds seem to make no difference to the flow of the yarns. And if the de Camp personality has intruded at all into the “Tranicos” episode, it may be in a tendency to tidy up, over-explain, and knit everything together in a way which Howard could never have done – but which wouldn’t have mattered one bit.

Not content just to see one of his stories sit side by side with the real thing, de Camp contributed an Introduction to King, detailing his new-found obsession. That obsession would linger, and drive the next four Conan titles.

Gnome Notes

Although uncredited, John D. Clark was the editor of this volume.

In his “Introduction,” de Camp states that Howard “drove thirty miles out into the desert” to shoot himself. Nothing so dramatic happened. He merely went to his car in the driveway to do the deed.

Reviews

Mark Reinsberg, Imagination, January 1954

King Conan is flamboyant blood-and-thunder, without depth or serious value, which however, cannot be denied its exotic appeal.

Contents and original publication

• “Introduction,” L. Sprague de Camp (original to this volume).

• Introductions to stories (from “An Informal Biography of Conan the Cimmerian” John D. Clark and P. Schuyler Miller, adapted from “Probable Outline of Conan’s Career,” in Robert E. Howard, The Hyborian Age, Los Angeles: LANY Cooperative Publications, 1938).

• “Jewels of Gwahlur” (Weird Tales, March 1935).

• “Beyond the Black River” (Weird Tales, May 1935 and June 1935).

• “The Treasure of Tranicos” (rewritten by L. Sprague de Camp, with an introduction by Lester del Rey, from an unpublished manuscript and published in Fantasy Magazine, March 1953 as “The Black Stranger”).

• “The Phoenix of the Sword” (Weird Tales, December 1932 missing the introduction, published separately as “The Nemedian Chronicles in The Sword of Conan).

• “The Scarlet Citadel” (Weird Tales, January 1933).

Bibliographic Information

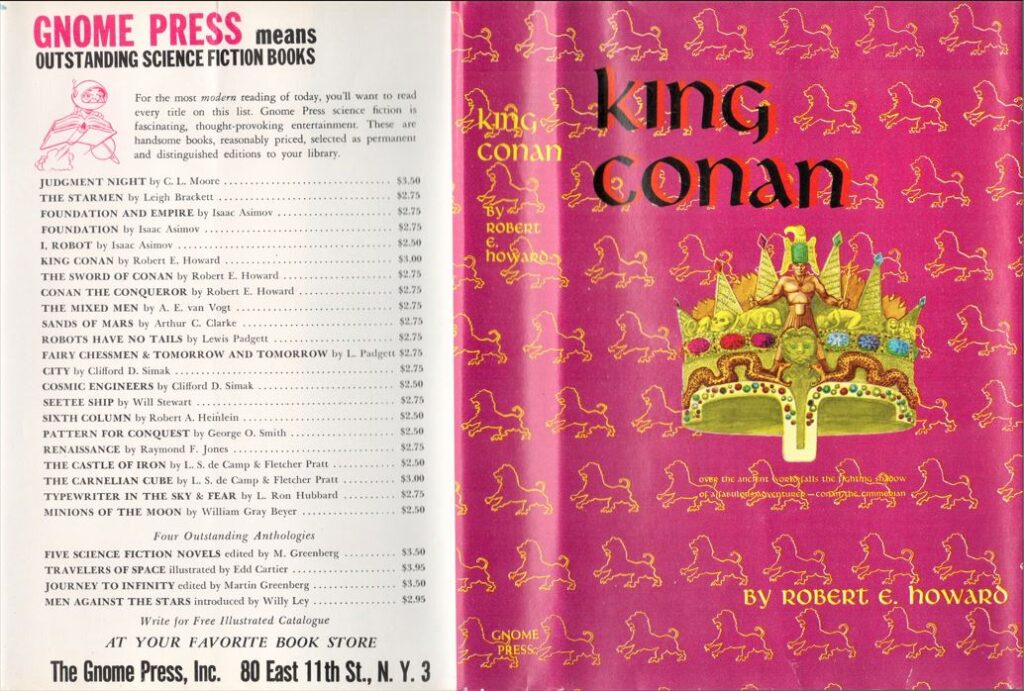

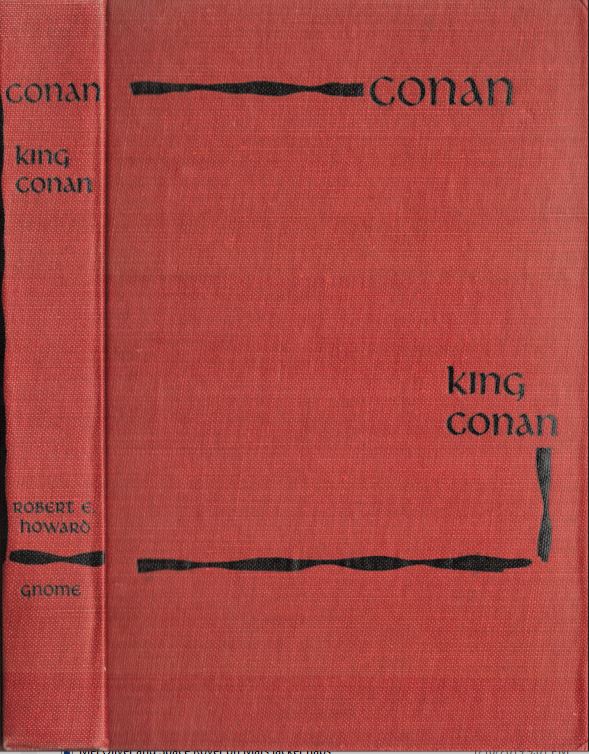

King Conan, by Robert E. Howard, 1953, copyright registration 2Mar53, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number not given [retroactively 53-8200], 255 pages, title #28, back panel #21, $3.00. 5000 copies printed. Hardback, red cloth, spine lettered in black. Jacket design by David Kyle. David Kyle map of Hyborean Age on front and rear endpapers. “First Printing” on copyright page. Printed in the United States of America. Title page adds “The Hyborean Age.” Back panel: 26 titles. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., N.Y. 3.

Variants

None known.

Images