A brand-new publisher, hoping to make as big a splash in the market as possible, will try to issue its first book with the biggest-name, most recognizable, most desired author. Arkham House legendarily did so with an H. P. Lovecraft collection. Hadley and FPCI both started with A. E. van Vogt. Buffalo Book Company, Fantasy Fiction Field, and Fantasy Press all chose Doc Smith. Shasta’s first fiction title was Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell. Lyon Sprague de Camp (1907-2000) and Murray Fletcher Pratt (1897-1956) were at the time right up there with those giants.

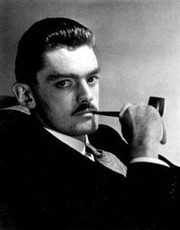

De Camp spent almost all his life as a writer despite his degree in aeronautical engineering from Cal Tech, where he edited the student newspaper, and a Master’s from the Stevens Institute of Technology. That background made him perfect for becoming one of John Campbell’s engineering-minded finds at Astounding, although his first story there actually appeared in the last issue edited by F. Orlin Tremaine. Though often described as cold and intellectually forbidding, he possessed a keen sense of satire and whimsy, which made him a favorite at Campbell’s fantasy counterpart, Unknown. There he teamed with Pratt for a series of historical fantasies, often set in the worlds of major writers like Shakespeare and Spencer.

Pratt was raised on the Seneca Indian Reservation at Tonawanda, New York and spent a year at Hobart College in Upstate New York. The lack of formal education wasn’t an obstacle for journalism and while moonlighting as a librarian and flyweight boxer Pratt worked for several newspapers in Buffalo from 1923-1926, the Pittsburgh Press in 1926 and 1927, and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from 1928 through 1930, mostly as a feature writer of history and biography. He wrote articles for magazines on the side and starting in 1930 gained prominence as a naval historian in the Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute. Eight major works of history, including The Navy, A History, appeared in the 1930s. Pratt picked up the pace in the 1940s, with a flock of books about the country’s war effort and work as a syndicated naval correspondent for the New York Post.

Pratt was raised on the Seneca Indian Reservation at Tonawanda, New York and spent a year at Hobart College in Upstate New York. The lack of formal education wasn’t an obstacle for journalism and while moonlighting as a librarian and flyweight boxer Pratt worked for several newspapers in Buffalo from 1923-1926, the Pittsburgh Press in 1926 and 1927, and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from 1928 through 1930, mostly as a feature writer of history and biography. He wrote articles for magazines on the side and starting in 1930 gained prominence as a naval historian in the Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute. Eight major works of history, including The Navy, A History, appeared in the 1930s. Pratt picked up the pace in the 1940s, with a flock of books about the country’s war effort and work as a syndicated naval correspondent for the New York Post.

Somehow, Pratt found time for the pulps. His penchant for collaboration can be found in his very first story, “The Octopus Cycle,” in the May 1928 Amazing Stories, as it was signed by Irvin Lester and Fletcher Pratt. So were his next four. Irvin Lester of course turns out to be a pseudonym. For Fletcher Pratt. Nobody knows why. Apparently, Pratt was born to be a Gnome writer.

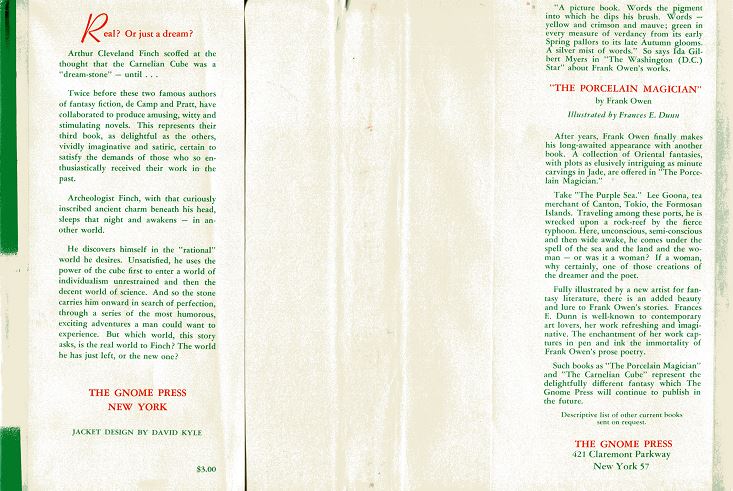

Pratt and de Camp first joined up for “The Roaring Trumpet” in the May 1940 Unknown. The rollicking plot has psychologist Harold Shea use symbolic logic as an entryway into other realities, a blend of fantasy and science fiction that exemplified Campbell’s sensibilities. [See The Castle of Iron] The war shut down their fiction writing almost completely so a new story from maybe the most famous writing pair in the field would be a cause of celebration. The Carnelian Cube features a cube about the size a golf ball, with Etruscan lettering carved into the carnelian stone. It transports its wielder to the world of his desires. (I’ve always liked to think that this was the inspiration for the Cosmic Cube that Stan Lee invented a few years later for Marvel Comics, a scientifically magic cube that transformed the wielder’s thoughts into reality.)

An element that will reoccur with great frequency throughout this chronicle is the interconnectedness of the then tiny world of f&sf writers. Pratt founded the dining club known as the Trap-Door Spiders that fellow member Isaac Asimov would fictionalize in a long series of mystery stories featuring the transparently pseudonymous Black Widowers. Other members were de Camp and John Clark, a Conan expert and de Camp’s roommate at Cal Tech. He will reappear in Conan the Conqueror. Clark was Pratt’s literary executor and a few years later married Pratt’s widow, Inge Stephens. An artist, Inge illustrated several of her husband’s books, including Tales from Gavagan’s Bar, a series of short stories by him and de Camp.

Pratt was as insatiably social as anyone in the field. He was the main New York host for the Hydra Club, a larger social club of New York f&sf professionals that included Gnome names like Martin Greenberg, Dave Kyle, Frederik Pohl, Judith Merril, and George O. Smith. Most of that group left for the suburbs by the early 1950s, when Pratt bought a 30-room house in New Jersey that got nicknamed the Ipsy-Wipsy Institute and sheltered multitudes of fellow pros until Pratt’s early death from cancer in 1956.

Gnome Notes

Dave Kyle never had an official title at Gnome, to my knowledge, but he was, along other tasks, de facto production manager. In a two-person operation, the production manager did every job imaginable. Kyle designed the text, the layout, and the cover for Carnelian. He worked with the printer, his own family’s Adviser Press of Monticello, New York, chose the paper, proofread the pages, made corrections to the printed copies, and may very well have swept out the office and lugged boxes of the bound and unbound copies. You don’t realize how many different operations go into the publishing of a book until you are faced with the reality of it.

Kyle was learning all this on the job. I don’t blame him in the least for making a few mistakes along the way. A book’s cover consists of three parts: the front cover, the rear cover, and the spine. The first two are fixed but the width of the spine depends entirely on the paper choice. Therefore you have to make your paper choice first and then design the dust jacket so that the spine is the correct width. Tenths of an inch make a difference at that point.

At some point in the process, Kyle goofed up. He designed the jacket based on a book with the same number of pages – but somehow failed to check for the thickness of the paper. Result: Carnelian turned out to be much thinner than he thought and the dust jacket is noticeably off center. The spine is a tenth of an inch too large, cutting off the C in “Carnelian,” and the back panel copy is pushed all the way to the edge and a bit beyond on some copies. While looking closely at the book you might also note its stark simplicity. The boards are utterly plain except for the spine text. The dust jacket doesn’t have a colophon or logo. Kyle would soon correct these omissions.

It’s what he did next that makes the book a classic bibliographic mess.

Kyle was standing by as the forms (32 pages on a large sheet that would be folded and the edges cut to create a 16-page signature) were put through the flatbed press. At some point during the printing he checked for errors. I’ve never seen a listing of points, although ESHBACH says Kyle corrected errors. But whatever else he did, he changed the copyright page. Instead of reading “FIRST EDITION” (in all caps) it now said “Second Printing” (in caps lower case). But this is not in any way a second printing. It’s the second state of the first edition. Again, a rookie mistake, but not a big deal.

CHALKER states that ESHBACH made the claim that none of the copies had a First Printing designation. That depends on how you read the section. ESHBACH does write “there never was a first printing – something unique in book publishing!” But that’s obviously a joke. In that same paragraph we get this:

After running a thousand copies of the first side of the large sheet … the forms were taken off for the next set of forms, another double 32 pages. While the second forms were being run, Dave personally corrected any errors he had found in the first double one thousand so that for the second run those sheets were corrected. Clear? I’m certain it isn’t.

Well, clear enough so that we can say that Kyle made the corrections after a print run of 1000. We don’t know, however, how many copies of the corrected forms were printed. What makes it a big deal is that there was an actual second printing of 1400 copies, probably in 1949, according to the ISFDB and CHALKER. It is clearly a true second printing with the binding and the text pages being 0.2” smaller. The type is identical, but kept the “Second Printing” designation. CHALKER gives 2500 plus 1400, ESHBACH and KEMP 3400 total. Unfortunately, KEMP follows this by stating “2nd edition, 1,400 copies printed. The ‘Second Printing’ was printed at the same time as the first, by adding those two words to the copyright page,” which contradicts ESHBACH and common sense. Going by its appearance, disappearance, and reappearance on the back panels, the second printing was made in 1949, clearly after the first printing sold out. ESHBACH says that it was “a so-so seller,” which makes no sense if a hurried second printing was needed just a year later. Carnelian was as well-publicized as any book in the late 1940s: The Fantasy Book Club (FBC) offered it, the FBC Bulletin featured it, one page Gnome advertising flyers flagged it, and ads for the FBC were in major professional and fan magazines. Amazing, Astounding, Super Science Stories, and Thrilling Wonder all reviewed the book, as did – astonishingly – The New York Times Book Review. The core f&sf audience couldn’t help seeing the title.

The second printing made its way to Canada somehow. The Science-Fantasy Distributors of Toronto placed an ad for the latest f&sf titles in the December 3, 1949 Montreal Daily Star that specifically dubs Carnelian as a second printing. I take that as another indicator that the second printing comes from late 1949.

Adding to the fog surrounding the variants is the bibliographer’s burden in describing the color of the second printing boards, made of something similar to the pressed cardboard that the Science Fiction Book Club would find at the bottom of the bin to use as the cheapest substance to bind their editions. For the first, but certainly not the last, time in Gnome history, a color from an alien spectrum bound the pages. Sellers equally flail, using words as non-synonymous as gold, beige, and light green. Other than saying that none of those descriptors truly convey the shunned non-entity of color that the boards convey, I’ll fall on my sword and give it as “beige,” just because I can blame something else for the word.

Carnelian set an unfortunate precedent. For the rest of its existence Gnome would sometimes go back to press for additional copies and sometimes print up all the copies at once but bind some of them later. In all cases, though, nobody bothered to change the “First Edition” designation on any of the copyright pages, even if the books are instantly distinguishable to even an amateur eye. No matter what, all later Gnome Press books are first printings, even if they aren’t.

Not surprisingly, this has led to endless confusion, with Carnelian leading the parade. Both CHALKER and KEMP mention this printing. CURREY does not: as an actual second printing, it’s beyond his scope. That the first printing has a second state equivalent to the many other second and later states of other Gnome titles he does include means that he probably should have mentioned the variant for consistency. Since he doesn’t, many sellers won’t mention any of the variants and you have to ask to know what it is you’re getting. Finding the actual second state seems to be harder than finding the second printing these days, although first state printings are relatively common. At this point you may want to ask yourself whether you really want to become a Gnome completist, or whether just finding a copy of each title is more than enough grief for one lifetime.

Collectors should also know – the classic cliché come to life – an unsigned copy of Carnelian seems to be rarer than a signed one. De Camp was a part of fandom and easily reachable at any of a thousand conventions. Pratt, however, socialized with pros rather than fans. His signature appears only on a few inscribed copies, which go for multiples of a de Camp signed copy.

Reviews

Isaac Anderson, The New York Times Book Review, December 5, 1948. [This preceded the Times’ f&sf review column, so it improbably appeared in the “Criminals at Large” mystery review column.]

The jacket copy describes this book as a “humorous fantasy.” It is a fantasy in a heavy-handed sort of way, but as for the humor, the less said the better.

Unsigned, Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1949.

The job is earthy, talkative, frequently witty. The authors have given full reign to a pair of highly fertile imaginations and the reader does not suffer thereby.

Contents and Original Publication(s)

- Chapters 1-23 (original to this volume).

Bibliographic information

The Carnelian Cube, by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Platt, 1948, copyright registration 1Nov48, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number not given [retroactively 48-28172], 224 pages, title #1, back panel #1, 252 pages, $3.00. 2000 copies printed, 1948; 1400 copies printed, 1949. Hardback. Jacket design by David Kyle. Printed in the United States of America by Adviser Press, Monticello, NY. Title page, jacket, and copyright registration adds “A Humorous Fantasy.” Back panel: Meet the Authors, text and pictures about De Camp and Platt. Gnome Press address given as 421 Claremont Parkway, New York 57.

Variants, in order of priority

1) Gray cloth, spine lettered in red. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page.

2) Gray cloth, spine lettered in red. “Second Printing” on copyright page.

3) Beige boards, spine lettered in red. “Second Printing” on copyright page.

Images

Pingback: Carnelian Cube Link Roundup | Jeffro's Space Gaming Blog