Comments

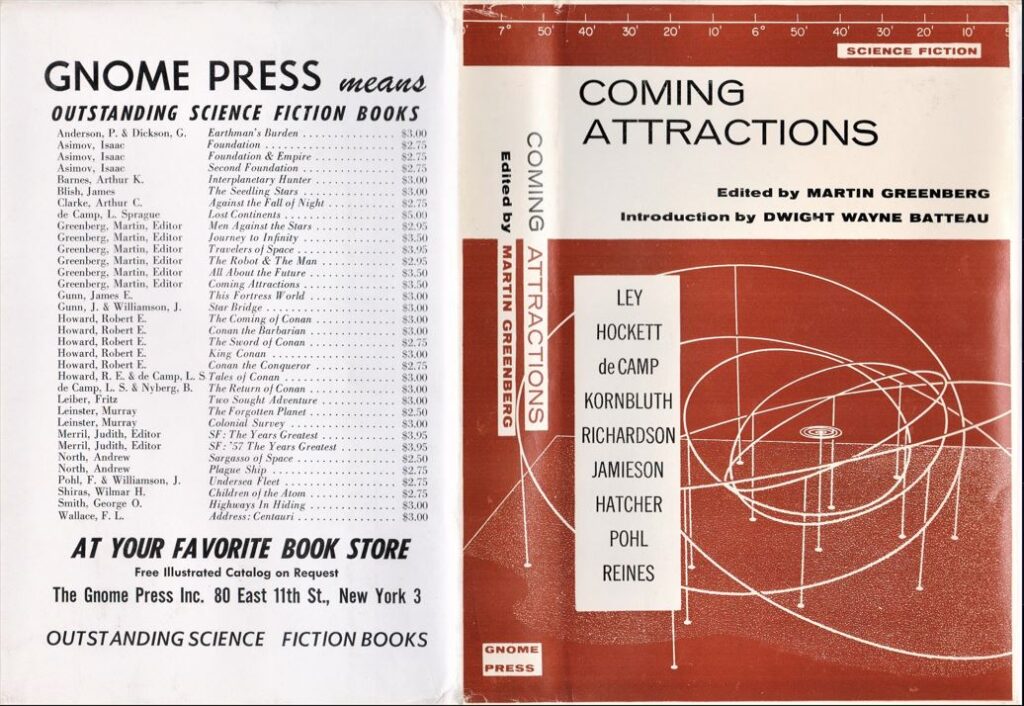

By 1957 Gnome Press was essentially alone among the many small f&sf publishing houses founded in the aftermath of WWII. Two others survived: the powerful Arkham House, although its fantasy orientation made it hardly a competitor, and the obscure Grandon Company, which would over the next year publish its last two titles (of five) before quietly slipping away. Gnome was first among equals because of Greenberg’s ability to keep slightly ahead of his market and give readers the best blend of hot new stuff and otherwise unavailable old favorites that hit every button.

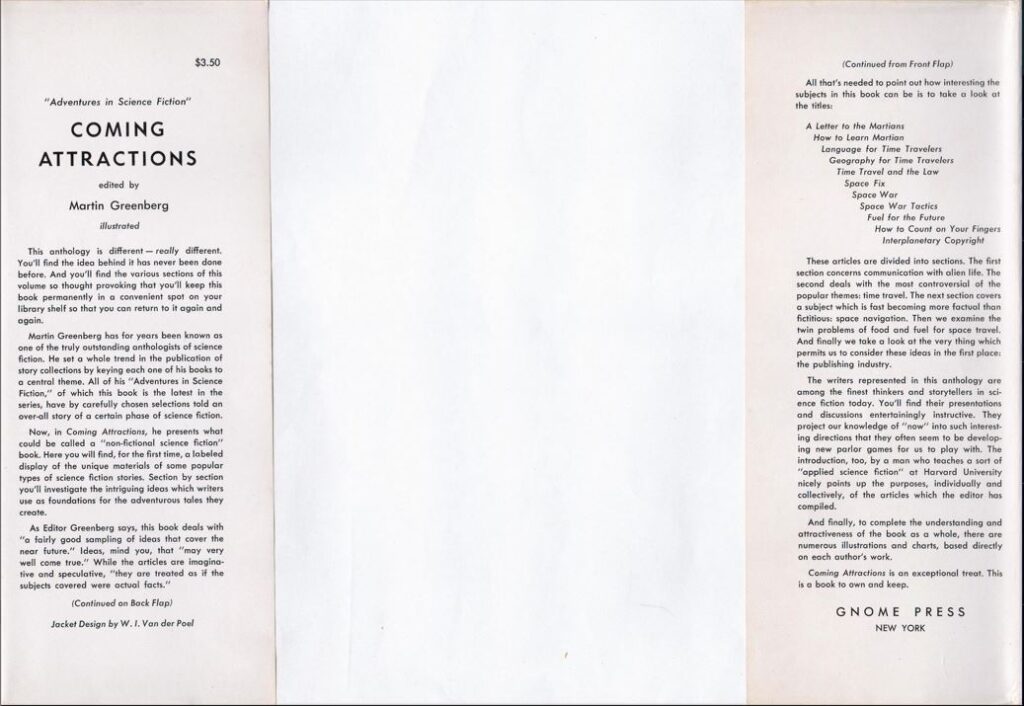

How else to explain Greenberg’s seventh and last anthology, a collection of nonfiction essays rigorously extrapolating the social dynamics of space and time travel a full six months before the launch of Sputnik?

True, Greenberg had already put out a collection of essays about space travel, The Complete Book of Outer Space, in 1953, but that was a reprint he had nothing to do with. He turned his gaze at his favorite source, the pile of ancient Astounding magazines sitting always near to hand, and combed through them for articles on the theme. He found a half dozen dating back to 1938 and padded them out with some less serious modern articles, including a coup, one of the last pieces from C. M. Kornbluth before his unexpected death a few months later. Voila. Instant anthology that must have looked very tasty on shelves in October 1957.

The anthology has an introduction by Dwight Wayne Batteau, a name only slightly more obscure today than it was in 1957. The flaps give no more information than he was “a man who teaches a sort of ‘applied science fiction’ at Harvard University.” I could find no biography online, so I’ve scraped a few fragments together.

Dr. Batteau was born in either 1913 or 1916 (sources differ) and was a 1948 graduate of Harvard. Part of the lateness is explained by a military career, during which he was an Air Force project officer and an Army Signal Corps officer for radar and missiles at the Watertown Arsenal. By 1956, when his Introduction was written, he had advanced to being an Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering there. He indeed taught “Applied Science Fiction,” the nickname given to his Engineering 200 course.

Batteau’s connection with science fiction started back in his undergraduate days when he and Warren Seaman, Assistant Director of the Harvard Computational Laboratory as of 1956, founded a sort of science fiction society. Their bull sessions did more than discuss the latest stories; they soared into more advanced issues by speculating on “the feasibility of such fanciful things as computing machines, automatic ‘brains,’ space rockets, and other amusing ‘toys,’” as an article in the Harvard Crimson put it. Their speculation was high-powered enough that John W. Campbell would come up to Boston take part. The informal group called itself the “Speculative Society” and grew over the next decade. Campbell continued visiting and as the Crimson somewhat hyperbolically put it, “the ‘Society’ would meet, and the following month Astounding Science Fiction would contain a story about robot brains and thinking machines.” Batteau had a special interest in “information machines” and had built a machine that would provide answers to any problem in logic.

Batteau’s subsequent career has some high romance to it. He turned himself into an expert on hearing and, after moving to Tufts University, developed a mechanical ear that he claimed was better than the hydrophone because it could hear directionally like a human ear did. He worked in 1965 with Gregory Bateson, a cyberneticist, who was director of research of the Oceanic Institute in Honolulu. Building on his earlier discoveries, Batteau made a microprocessor-powered device that translated human speech into a series of whistles that dolphins could purportedly understand, and then convert their whistles into human speech.

Whether that was a genuine breakthrough or crackpot technology is unknown. G. Harry Stine, who was working with Batteau, said in a 1979 Omni article that Batteau died in 1967 “of a massive myocardial infarction while scuba diving with dolphins in Hawaii.” Contemporary newspaper reports tell a totally different story. Though only four weeks after moving to Honolulu for what might have been his dream job, heading the research into dolphin communication, witnesses described him taking off all his clothes and wading into the ocean. The medical examiner ruled it was death by drowning after his body was found in shallow water a few feet from shore. The project wasn’t merely closed down; it was disappeared. A 2000 article in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin claimed that “The Navy classified its dolphin program when Batteau mysteriously washed up dead on the beach in Waimanolo [where he lived] and then ‘sanitized’ all evidence of his program except the papers.”

An inexplicable mystery rivaling the best of Gnome’s homegrown variety.

Gnome Notes

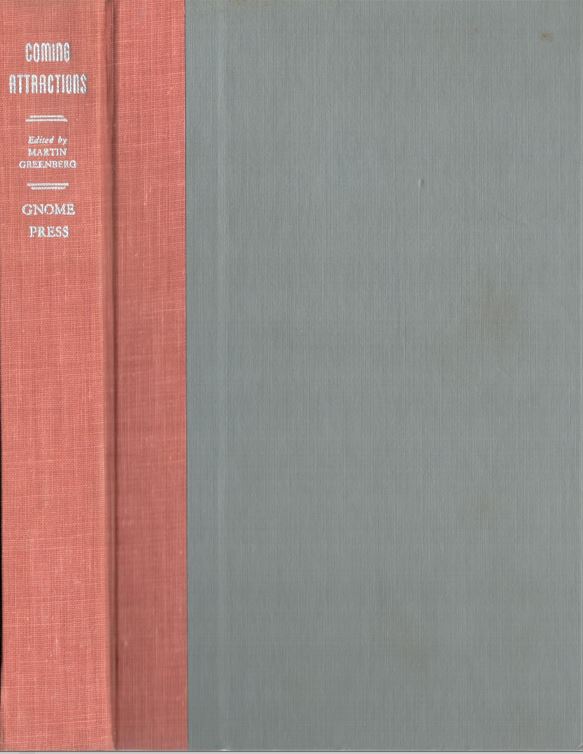

A sign of Gnome’s desperate financial situation can be seen just be flipping through the pages. They are the cheapest form of untrimmed pulp, brown and decaying with age, a far cry from the thin, high-quality, acid-free paper of his early anthologies. The cloth spine also lacks their embossing, undoubtedly another cost-saving measure.

This undoubtedly prescient but instantly dated anthology has never been reprinted in any form.

Reviews

Theodore Sturgeon, Venture Science Fiction, July 1957

[All] convention committees [should] polish up an award, possibly a brand new kind of award — say, “For the Book Best Filling the Longest-Felt Need in Science Fiction.”

P. Schuyler Miller, Astounding Science Fiction, December 1957

Marty Greenberg, who by this time should have no trouble defending his title as the science-fiction publisher with the best all-around books, has taken a brand-new approach in his latest “theme” anthology. … [I]t’s one you should recommend to your local public library.

Contents and original publication

• “Preface,” Martin Greenberg (original to this volume).

• “Introduction,” Dwight Wayne Batteau (original to this volume).

• “A Letter to the Martians,” Willy Ley (Thrilling Wonder Stories, November 1940, as “Calling All Martians”).

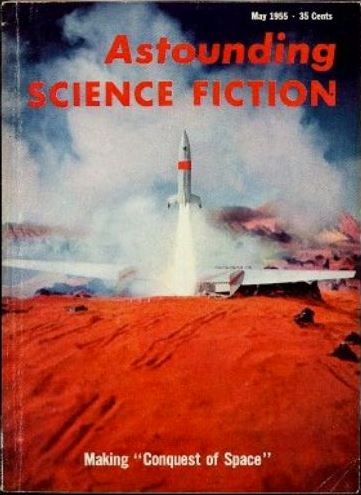

• “How to Learn Martian,” Charles F. Hockett (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1955).

• “Language for Time Travelers,” L. Sprague de Camp (Astounding Science-Fiction, July 1938).

• “Geography for Time Travelers,” Willy Ley (Astounding Science-Fiction, July 1939).

• “Time Travel and the Law,” C. M. Kornbluth (original to this volume).

• “Space Fix,” R. S. Richardson (Astounding Science-Fiction, March and April 1943).

• “Space War,” Willy Ley (Astounding Science-Fiction, August 1939).

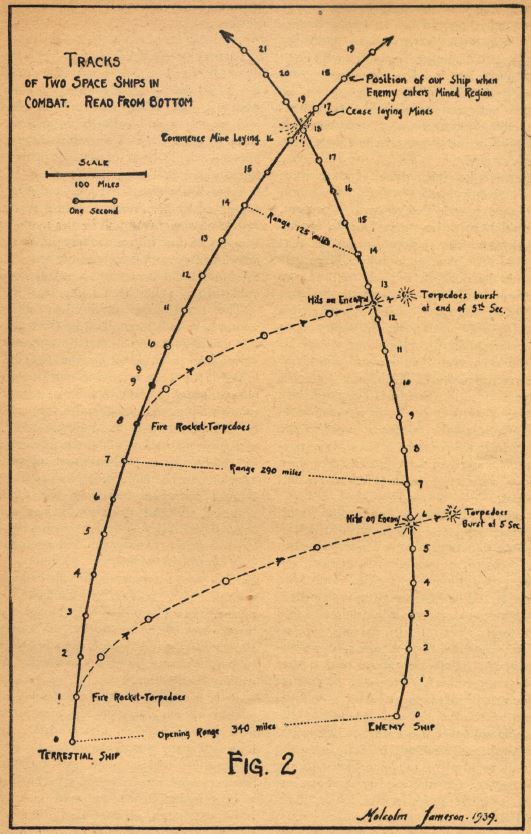

• “Space War Tactics,” Malcolm Jameson (Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1939).

• “Fuel for the Future,” Jack Hatcher (Astounding Science-Fiction, March 1940).

• “How to Count on Your Fingers,” Frederik Pohl (Science Fiction Stories, September 1956.

• “Interplanetary Copyright,” Donald F. Reines (Information Bulletin of the Library of Congress, August 11, 1952, as “The Shape of Copyright to Come”).

Bibliographic Information

Coming Attractions, edited by Martin Greenberg, Adventures in Science Fiction series 6, 1957, copyright registration 15Mar57, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 56-7845, title #59, back panel #33, 254 pages, $3.50. 5000 copies printed. Hardback, gray cloth with red cloth spine and silver lettering. No embossing on front cloth. Jacket design by W. I. Van der Poel. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Manufactured in the U.S.A. Printing & binding by: H. Wolff, New York, N.Y. Back panel: 34 titles. Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

Variants

None known.