Comments

Journey to Infinity contains the best prank in the history of our in-bred field, chock full of in-jokes, generation-long feuds, and literary hatreds though it might be. The joke carries a special subversion because it’s played on the boss, the man who ran the company, and whose name is on the cover. I can’t improve on ESHBACH, the first to reveal the story, so I’ll just quote him in full.

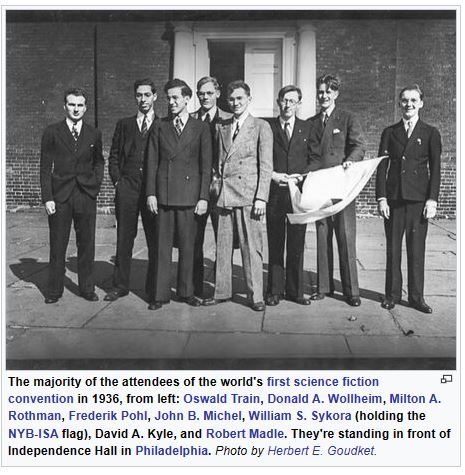

As mentioned earlier, probably the most successful ventures of Gnome Press were its theme anthologies. They were credited to Marty Greenberg, who unquestionably was an idea man, but it is my opinion that the collections were actually the work of Greenberg and [David] Kyle. Marty disputes this, insisting that he and he alone was responsible for the concepts and the story selections. Be that as it may, it is fact that the material signed by Greenberg was written originally by him, and then rewritten by Kyle to make the copy suitable for publication. Marty never professed to be a writer. All of the other material which might be designated editorial comment was Kyle’s work. Lest this seem to be a claim which cannot be substantiated, a careful examination of the second anthology, Journey to Infinity, will prove the assertion.

Each story in the collection begins with a comment by the editor tying the pieces together. There are twelve stories in the book – just enough to spell out “D-A-V-I-D-A-K-Y-L-E-E-D,” or “David A. Kyle, Ed.” without the punctuation, using the first letter in each introductory paragraph to form an acrostic. When Marty Greenberg read the first draft of this chapter [in 1983] it was his first knowledge of Kyle’s long-concealed trick – and I don’t think he was overjoyed at the revelation!

Only someone with one foot out the proverbial door pulls a prank of this magnitude, even given the unlikelihood of its being discovered. (How many more are out there that will never come to light?) Kyle, 32 and a WWII veteran, used the GI Bill to get a degree from Columbia earlier in 1951. Though Kyle officially stayed part of the business until 1954, the fact that Greenberg hired the first of a series of assistants in 1952 indicates that he could no longer depend on Kyle to do all the grunt work. The parting seemingly was amicable, though it demonstrated the universal truth that small presses couldn’t generate sufficient income for two at the top.

Gnome Press

Now comes another Gnome Press mystery, one of the deepest. Starting with Men Against the Stars, Greenberg put out five anthologies in the Adventures in Science Fiction Series. ESHBACH says, above, that this was the second anthology. That’s easy to confirm. Greenberg’s [Kyle’s] Foreword calls it “this second book” in the series. The pre-title page lists only Men Against the Stars and Journey to Infinity. Moreover, the Foreword to Travelers of Space states conclusively that it is “the third volume in our Adventures in Science Fiction series,” and lists all three volumes on page 14. For further proof, the back cover on the first printing of Travelers of Space includes Journey to Infinity and Foundation, which was the last title to be published in 1951. Journey to Infinity, in stark contrast, does not list Travelers of Space or Foundation, substituting older titles.

Few things in the entire history of Gnome are as clearly and multiply sourced as the order of the Adventures in Science Fiction Series anthologies. So why did ESHBACH himself put Travelers in Space ahead of Journey to Infinity in publication order? Why was this copied by CHALKER? And by KEMP?

Gnome was a shoestring operation. Greenberg and Kyle learned on the job and made mistakes, often quite odd ones, as they did so. Even so, is it conceivably possible that they put out the boss’s personal pet project titles in the wrong order? I think not. And I have a theory that might explain this oddity of oddities.

Mark Owens and Jack L. Chalker, bookdealers, published The Index to the Science-Fantasy Publishers in 1966, out of a need to provide information barely available anywhere else, much less in one spot anywhere else, about the small specialty f&sf presses. This is so long ago, in such a different collecting environment, that Chalker’s condemnation, in his Introduction, of unscrupulous book dealers charging $12 or more for the 1946 Arkham House book West India Lights makes no sense until he reveals that the press was still selling the book new at the original cover price of $3.00. The Outsider and Others, Arkham’s first book, from a press created to republish H. P. Lovecraft’s work, was already out of print, though, and selling for the “gigantic” price of $100. The cheapest price I find today is $2,500, and a copy in excellent condition will run $10,000 or more. Nobody had a clue in those days how valuable these odd, few, easily-tossed titles would become. Nobody could have thought that the most minute points of publication would be worth thousands in value.

The Index wasn’t a scholarly work, but a fan publication, a mimeographed text limited to a small number of copies to aid friends and collectors. Owens did the original; when it got spoiled in printing Chalker stepped in to rush it out, helping to correct errors that had slipped through and already found in that short period. (We’re already deep in a bibliographic quagmire. Other than the owners’ copies and two to the Library of Congress, the first edition doesn’t exist. The reprinting is called the Second Edition, although you’ll see that nowhere except on the copyright page. The hugely expanded revision in 1991 is called the Third Edition and has Chalker’s name first, hence my referring to it as CHALKER. But there are only two variants nevertheless.)

Earlier I emphasized that Travelers had a copyright registration of 1952, though. This is a fact, yet Owings was not wrong. Travelers is marked “COPYRIGHT 1951” on its copyright page. This is also a fact, and a correct one. The discrepancy can be explained by referring to the Catalog of Copyright Entries, which appends the 3Jan52 date with “(in notice: 1951)”. Books that were received at the end of the calendar year sometimes were not marked as registered until the next calendar year, but received a copyright date properly of the year of submission. Travelers is the first Gnome book to have this happen; it would not be the last. Nevertheless, Journey is clearly a product of January 1951 and Travelers is from December 1951 and the latter cannot possibly precede the former.

ESHBACH, publishing in 1983, strove to correct many of these problems. He talked again to founders and got them to pull out better records. His lists were in true publication order, had corrected print runs, and listed known reprintings, revealing along the way that Journey is one of three in the ASF to have a true second printing.

His information on Gnome came directly from Greenberg. ESHBACH calls it “the first really authoritative list ever published.” Unfortunately, some facts were lost to time and he was capable of mistakes like every other list maker, without the Internet bestowing upon him the gift of infinite incremental revisions. One major mistake is that he omits mention of the third Gnome book, Pattern for Conquest. That simple copying error, in a world before cut and paste, is understandable.

So when he lists Travelers just ahead of Journey, I normally, like every other bibliographer since, would simply copy that order myself. They would be title #16 and title #17, if Pattern is added back in. And yet both numbers are wrong. Once the evidence from copyright registrations and back panels is accounted for, it is clear that these are actually #12 and #18, respectively. Greenberg did not dump two anthologies on the market at the same time. He sensibly spaced them out a year apart, as he did for the first four of the ASF, released in early 1950, 1951, 1952, and 1953, before a two-year gap to the last in 1955.

As he did with Men, CHALKER lists the second printing as being from 1955. However, the 30-title back panel is identical to that of The Robot and the Man, published in March 1953 and bearing titles only through part of 1953. (This back panel was also used on the second printing of Travelers in Space, clearly making them a set.) Therefore, the evidence is overwhelming that it was released in 1953.

— cover art by Earle K. Bergey

Reviews

Groff Conklin, Galaxy Science Fiction, April 1951

Despite too skeletal a form [i.e., too few stories], Journey to Infinity is a good buy for anyone who likes top-grade science fiction.

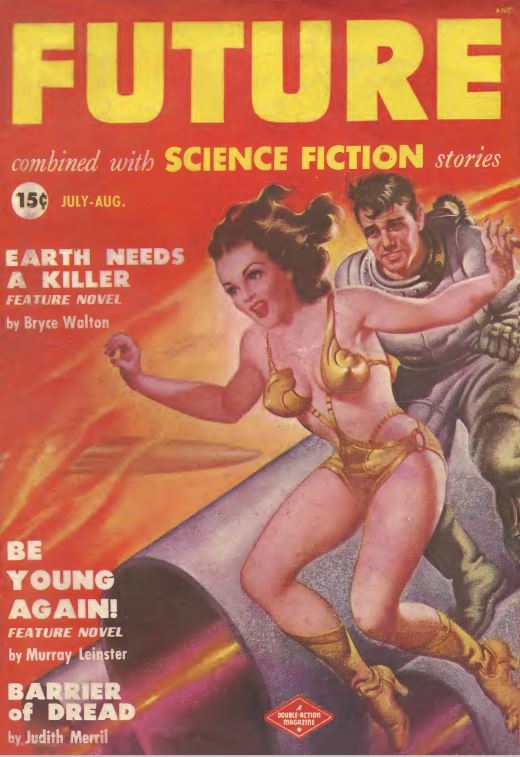

Robert W. Lowndes, Future Combined with Science Fiction Stories, November 1951

But the collection simply doesn’t jell, nor can I see it as being worth the $3,50 the publishers ask for it.

Contents and original publication

• “Foreword,” by Martin Greenberg (original to this volume).

• “Introduction,” by Fletcher Pratt (original to this volume).

• “False Dawn,” by A. Bertram Chandler (Astounding Science Fiction, October 1946).

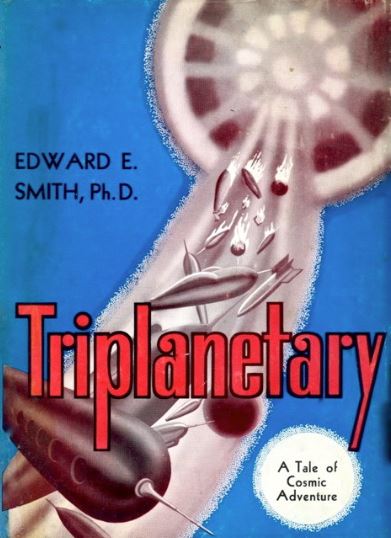

• “Atlantis,” by Edward E. Smith, Ph.D. (Amazing Stories, January 1934).

• “Letter to a Phoenix,” by Fredric Brown (Astounding Science Fiction, August 1949).

• “Unite and Conquer,” by Theodore Sturgeon (Astounding Science Fiction, October 1948).

• “Breakdown,” by Jack Williamson (Astounding Science-Fiction, January 1942).

• “Dance of a New World,” by John D. MacDonald (Astounding Science Fiction, September 1948).

• “Mother Earth,” by Isaac Asimov (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1949).

• “There Shall be Darkness,” by C. L. Moore (Astounding Science-Fiction, February 1942).

• “Taboo,” by Fritz Leiber (Astounding Science Fiction, February 1944).

• “Overthrow,” by Cleve Cartmill (Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1942).

• “Barrier of Dread,” by Judith Merril (Future Combined with Science Fiction Stories, July-August 1950).

• “Metamorphosite,” by Eric Frank Russell (Astounding Science Fiction, December 1946).

Bibliographic Information

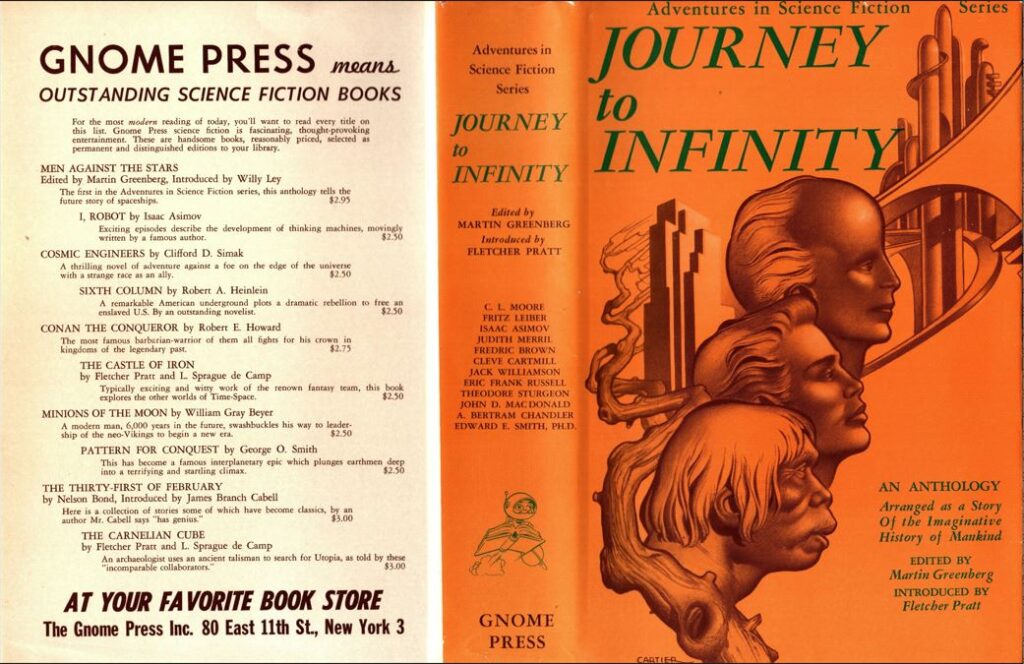

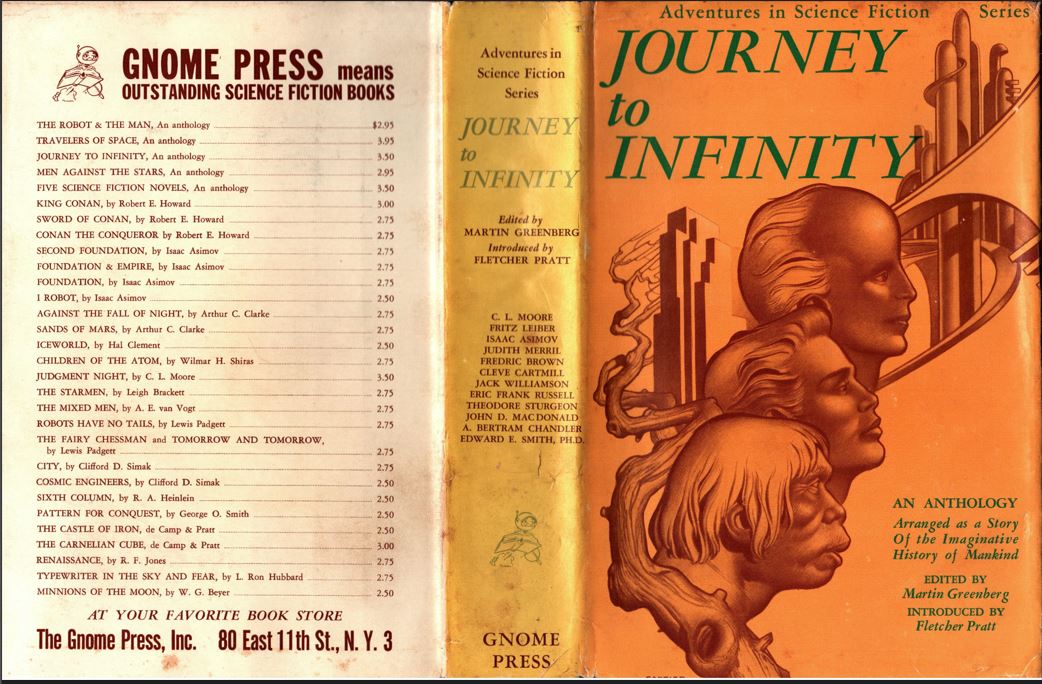

Journey to Infinity, Edited by Martin Greenberg, Adventures in Science Fiction series 2, 1951, title #12, back panels #12,22, copyright registration 3Jan51, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number not given [retroactively 51-9207], 381 pages, $3.50. 5000 copies printed 1951; 2500 printed 1953?. Hardback, dark green cloth-backed spine with fawn cloth and spine lettered in silver. Man reaching toward star embossed into front cloth. Jacket illustration by Edd Cartier. “FIRST EDITION” on copyright page. Manufactured in the United States of America. Colonial Press, Inc. Printers. David Kyle, Book Designer.

Variants, in order of priority

1) DJ Spine: Gnome “spaceman” 1.1”. Back panel: 10 titles, prose intro, Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., New York 3.

2) DJ Spine: Gnome “spaceman” 0.7”. Back panel: 30 titles, no intro, Gnome Press address given as 80 East 11th St., N. Y. 3. Second printing from 1953, but not indicated as such.

Images

— Journey to Infinity, jacket front, variant 1 — Journey to Infinity, jacket front, variant 2

— Journey to Infinity, jacket front, variant 2

— Journey to Infinity, jacket flaps, all variants