Literature starts with mythology, what we today recognize as fantasy whether or not the original creators did. Realistic stories about everyday life developed much later and became the norm surprisingly recently. For thousands of years storytelling involved the uncanny and the unknown, tales of gods and goddesses, magical creatures, witches and warlocks, ghosts and goblins, weird peoples in far-away lands, travel to the sun and moon, heaven and the afterlife, and of the spookiness that lurked just around every imaginary corner and many real ones.

As the modern prose fiction form that came to be known as the novel evolved, fantastic tales began to be edged toward the margins but never disappeared. Writers continued to ply their imaginations and invent new forms of the fantastic, including the gothic novel, utopias, vampires, travel through time, and imaginary futures. After the advent of the industrial revolution, stories embraced science and technology as plot drivers, with two seminal stories published early in the 19th century: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” in 1816 followed closely by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus in 1818, both using artificial life-forms to comment upon humanity.

Dozens of writers pioneered branches of the fantastic before1900, from Edgar Allan Poe to Lewis Carroll, H. Rider Haggard to Mark Twain, and Jules Verne to H. G. Wells.

Though noted for their uncanny tales, the majority of these writers also wrote mundane fictions that their publishers released in complete concordance with their fantastic stories. Commercial publishing had yet to stratify fiction into genres, although a distinction between high fiction, that published usually in hardbacks from distinguished houses, and low fiction, normally found in paper covers released by the interchangeable hundred by schlock merchandisers, appeared as soon as the rotary press did in the mid 19th century. Low fiction catered to the lower classes, especially in America, where the emphasis on public schooling created a literate audience for popular, easy-to-read, and often sensationalistic yarns. These nickel and dime novels can today be sorted into recognizable types: romance, mystery, western, the foundation of modern genre fiction. The rotary press had allowed the number of copies of any given title to increase by a power of ten and the railroads carried boxes of these books to every corner of the country. (Indeed, they were often called railroad novels, designed to pass time on long trips and to be tossed afterward.) Collectively they outsold high fiction by orders of magnitude.

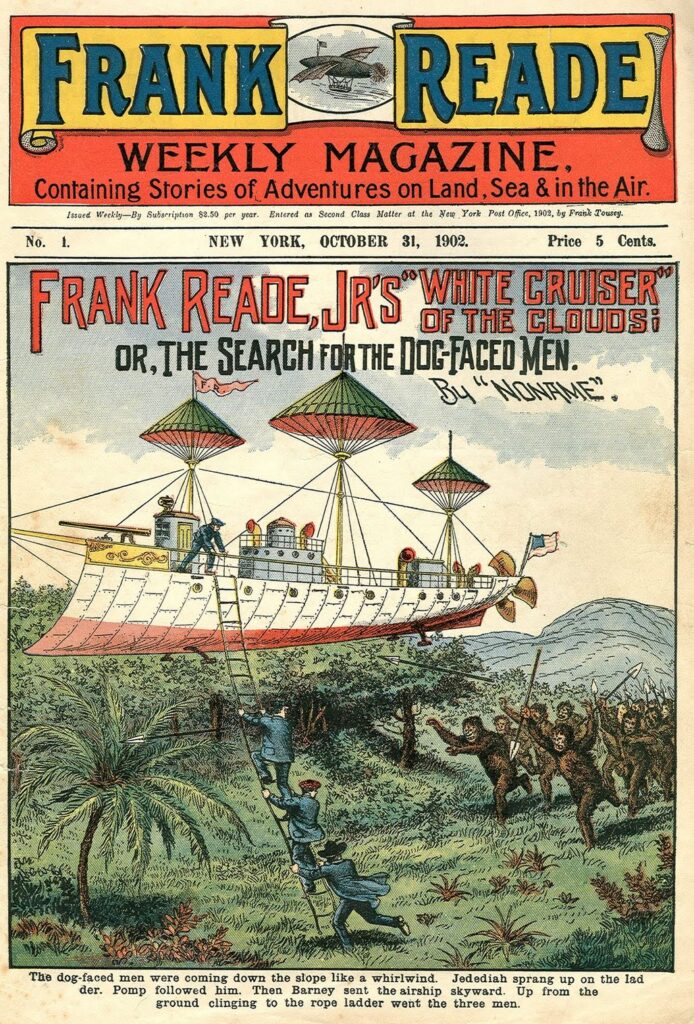

A few entrepreneurs created an even faster and cheaper form of word delivery, the story magazines. Starting at eight pages, but quickly increasing to 16 or 32 pages, these weeklies were printed on cheap newsprint with the advantage of being able to incorporate frequent illustrations to break up the small, dense type that crowded tens of thousands of words into each issue. Written mainly by young men using the newfangled typewriters for speed, a few hacks could turn out hundreds of “novels” over their careers, almost always in familiar genres established by the dime novels. Adventure novels set all over the globe begat a type of proto-science fiction that starred a young genius whose amazing inventions could conquer the land, sea, and air. None compared to Frank Reade, Jr., whose adventures were credited to “Noname,” actually Luis Senarens. Frank is forgotten; his successor, Tom Swift, lasted through the entire 20th century.

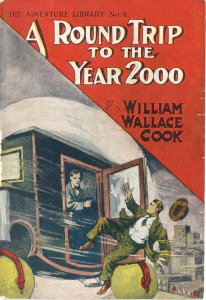

The story weeklies were superseded by pulp magazines, large, thick magazines printed on crude, thick paper, somewhat sturdier than newsprint. These at first were composed of general interest fiction, a term that then encompassed all forms of genre. H. G. Wells’ work appeared in the prestigious “slick” magazine Cosmopolitan; William Wallace Cook, the first modern American science fiction writer, was a pure product of the pulps, his serialized novels appearing almost every issue for several years in Frank Munsey’s The Argosy, considered the first pulp magazine. In A Round Trip to the Year 2000, Cook’s future is run by robots, or as he called them twenty years before Capek coined the term, muglugs. “Listen: Any machine that lightens a laborer’s toil is a blessing, but any machine that eliminates the laborer is a curse.” That’s a century of robot stories in a nutshell. Social commentary wrapped in continuous action sold well. Munsey added to his line of fiction pulps and made sure his editors featured some technological fiction in each.

Pulp publishers always looked for an edge. Editors noticed that readers would complain that their favorite story style might be left out of or skimped in an issue of general fiction. The idea of devoting a specialized magazine to one style of story was irresistible. Fiction magazines featuring railroads and sea stories appeared before 1910. The first modern genre pulp took a few more years. Munsey’s main competitor Street & Smith debuted Detective Story Magazine with the October 5, 1915 issue, continuing a dime-novel series, Nick Carter Stories. The next such pulps on the stands completed the triad of popular genres, Western Story and Love Story.

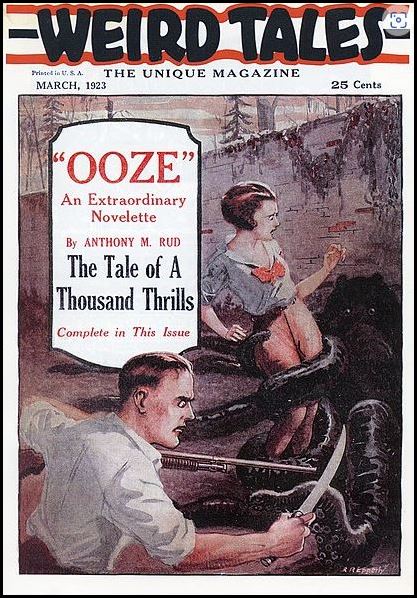

Then, in 1923, publishers stuck their toes into other genres, with the September debut of Sports Story Magazine and the March introduction of Weird Tales, a hodgepodge of “unusual fiction,” incorporating fantasy, horror, and what is now called science fiction.

Hugo Gernsback had already been running such stories in his non-fiction magazines, especially Science and Invention. In that seminal year of 1923, he included a “Scientific Fiction” issue, with a half-dozen stories. The response was overwhelming. Gernsback added Amazing Stories to his line in April 1926. First named by Gernsback “scientification” but becoming “science fiction” in 1928, the genre thrived in the short form, never to pass a month without such a specialized magazine, usually several, issued down to the present day.

Nevertheless, the early years were more commercially precarious than normally remembered. Weird Tales needed to be rescued by its printers. Gernsback’s magazine line went bankrupt in 1928, though he quickly returned with a series of Wonder magazines to compete with Amazing’s new owners. Astounding Stories of Super-Science launched in 1930, but missed several issues in 1933, a year in which all the magazines occasionally retreated to bi-monthly status.

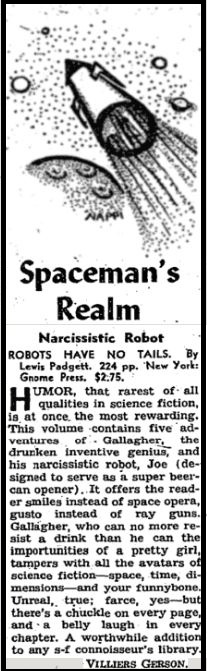

Certainly the Depression played a huge part, but the genre had more encompassing problems. The stories weren’t very good. It was one thing for the leading fiction magazines in the country to find a single good story an issue amongst the deluge of submissions and quite another to fill multiple low-paying monthly magazines with anything more than minimally professional hackwork. The editors of the nascent genre had to find and develop their own cadre of writers from the typically very young and inexperienced enthusiasts who latched on to unusual fiction and wanted to make it their own. As the genre matured and developed it increasingly drew in writers of multiple styles and interests. Several of the more noted would be published by Gnome, including Murray Leinster, Fletcher Pratt, Frank Owen, Edward E. Smith, Robert E. Howard, Jack Williamson, and John W. Campbell.

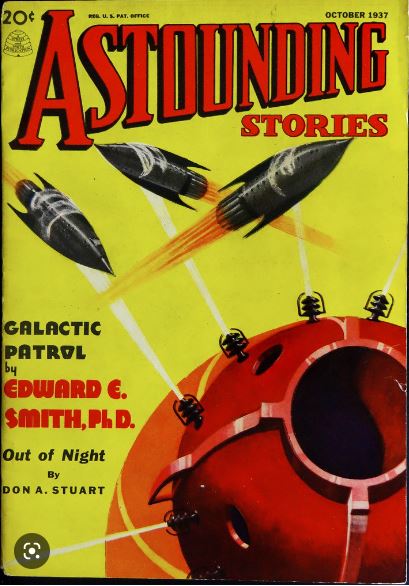

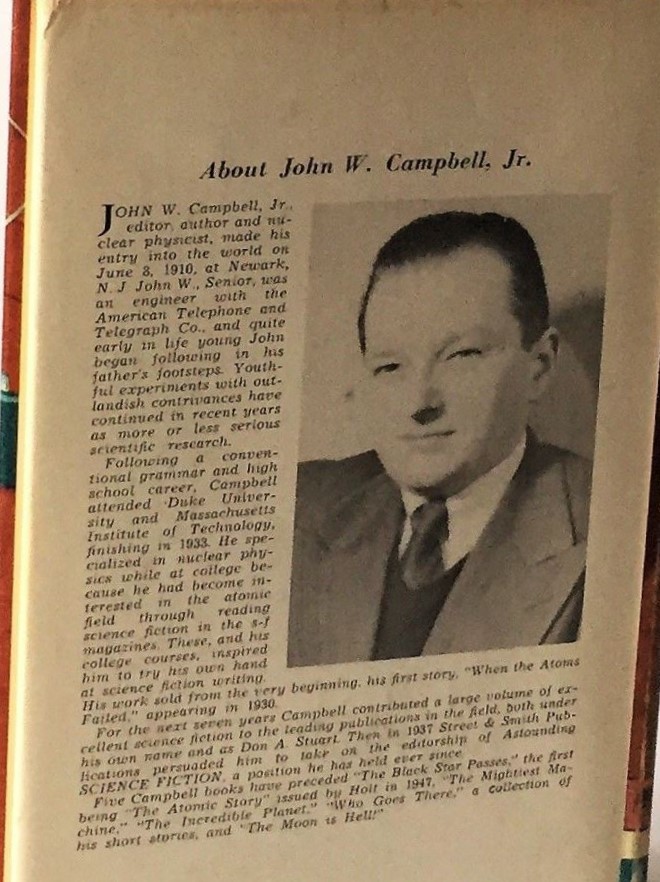

Campbell would take over as Astounding’s editor in 1937, when he was only 27 years old. That date is considered the beginning of modern science fiction, a different animal from the “Super-Science” stories and fictionalized lectures that marked the Gernsback era. Campbell was himself a leading practitioner of super-science but recognized that a more sophisticated approach was necessary for the field to grow and attract readers in a new era. He espoused a version of realism that was captured for posterity in Anthony Boucher’s roman à clef Rocket to the Morgue: “I want a story that would be published in a magazine of the twenty-fifth century.”[1] The wish was more style than reality, to be sure; no writer ever captured a future even twenty-five years away.

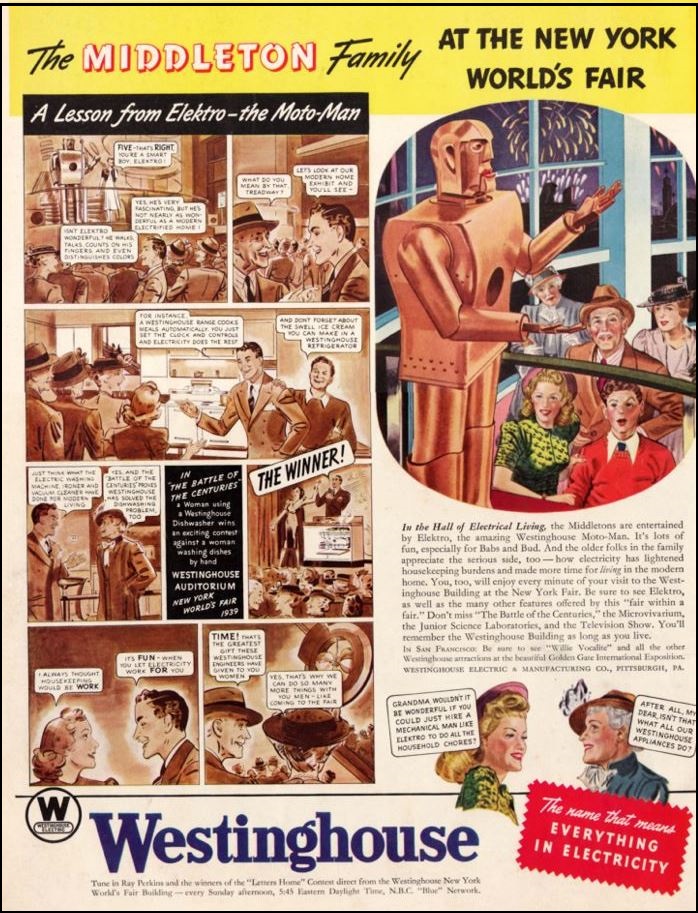

The Campbellian future was greatly influenced by the ongoing Depression. As I have written elsewhere, Carper’s First Law is that The Future is Never About the Future. It Is Always About Today. Every major system in society appeared to be failing in the 1930s, with a single exception. The decade was filled with heroic engineering successes – the tallest buildings, the biggest dams, the first expressways – and major scientific breakthroughs, including the splitting of the atom. Campbell, although his degree was in physics, was an engineer at heart, forever tinkering with devices in his basement. His vision of the future therefore centered on clear-thinking, rational engineers providing answers to societal crises, an echo of the Technocratic movement that called for replacing politicians with scientific experts. (Some science fiction writers had participated in the flare-up of Technocracy in the early 1930s and Gernsback put out two issues of Technocracy Review in 1933.) This proved to be a narrow, even blinkered, vision, but it resonated powerfully with an audience who passionately wanted to see that future come true, as would the rest of America when the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair superbly dramatized it as the World of Tomorrow, complete with robots.

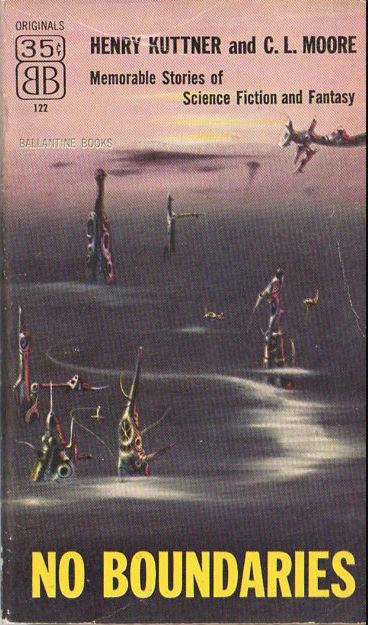

Campbell immediately changed the name of the magazine to Astounding Science-Fiction, making it the first in the genre to include the critical words “science fiction” in its title. Although he retained ties to some of the older writers, especially Smith and Williamson, he found, encouraged, and all-but-partnered with a batch of newcomers and brought forth better efforts from some who had already seen success in the genre. The list of writers who appeared in Astounding between 1937 and 1943, when many of them had to stop writing because of the war, is virtually synonymous with a Golden Age of science fiction and also with Gnome. In order of appearance: Nat Schachner, L. Sprague de Camp, L. Ron Hubbard, Clifford D. Simak, Henry Kuttner, A. E. van Vogt, Frederik Pohl, Robert Heinlein, Leigh Brackett, Isaac Asimov, Raymond F. Jones, C. L. Moore, Murray Leinster, Hal Clement, George O. Smith, and Fritz Leiber. Even Nelson Bond, definitely not known as a science fiction writer, made a few early appearances in Astounding. (Other major names included Theodore Sturgeon, Eric Frank Russell, Anthony Boucher, Robert Moore Williams, Malcolm Jameson, and Lester del Rey, whose books were published elsewhere but who all appeared in Gnome short-story anthologies.)

Heinlein would become Campbell’s fictional alter ego, apotheosizing the sanely heroic engineer. Asimov made a name for his robot stories, which were little more than engineering puzzle tales, and for his Foundation series, a technocrat’s dream of applying equations to messy human emotions. Clement was the hardest of hard-science writers, setting his stories on meticulously thought-out alien worlds with the appropriate lifeforms. Simak and the team of Kuttner and Moore were the closest to humanists, basing stories on emotions rather than calculations. Collectively, the writers of Astounding defined a certain type of science fiction that would, for good and bad, dominate a huge segment of the field for decades.

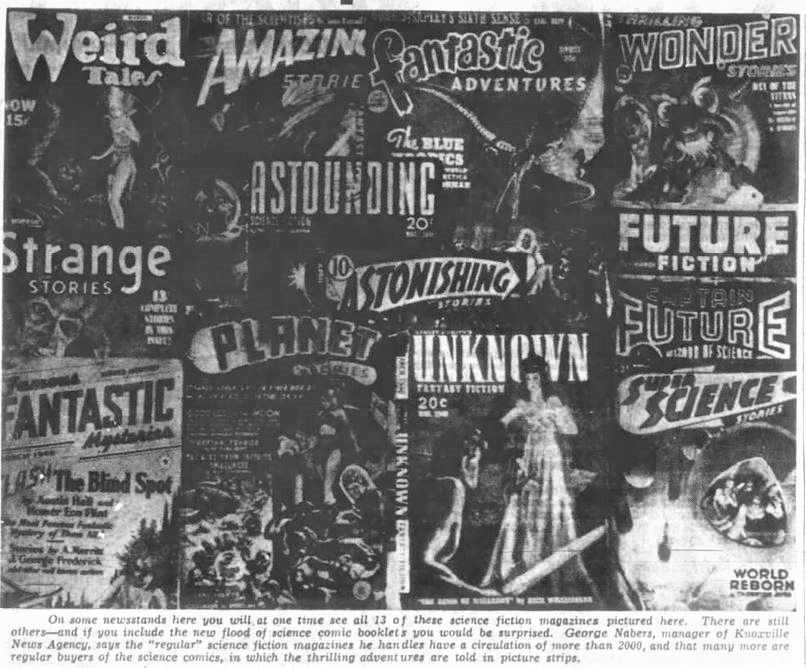

Even so, Campbell’s brigade remained virtually invisible to readers who didn’t pick up issues of Astounding or its fantasy companion Unknown (save the few who wrote and made names for themselves in other pulp genres). Science fiction had not outgrown the odoriferous reputation from Gernsback era “scientifiction” that stuck to the genre like shit on a sandal. The uninitiated judged the magazines by their covers, many of them prominently displaying classic “bug-eyed-monsters” printed in gaudy colors that all-too-often correctly reflected stories designed by the semi-literate for the nearly-illiterate.

In the ranking of pulp genres by the literati, science fiction hovered close to the bottom, above perhaps only the “spicy” magazines. The tiny number of newspaper reviews of the occasional book that saw print were seldom favorable. Influential magazines were scathing. In 1943, e.g., The New Yorker said that the audience for science fiction “composes what might be called the stupefied section of the reading public.”[2] “This besotted nonsense is from the group of magazines known as the science pulps” wrote Bernard DeVoto in Harper’s in 1939, after giving some embarrassing examples, and going on to say, “It is easy enough to classify these exhibits as paranoid phantasies converted into trivial fiction for the titillation of tired, dull, or weak minds.”[3] Perhaps even more important is what can’t be found. Virtually no mention of the field can be found in mainstream magazines (other than “how to” articles in writers publications) during the decade of the 1930s before these late post-Campbell mentions, meaning that these slams were almost certainly the first introduction to the field everyday readers received. Science fiction was literally beneath notice.

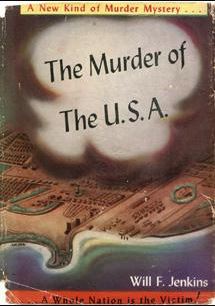

World War II provided the proverbial slap in the face. Neither pundits nor ordinary citizens could ignore the blazing headlines about V-2 rockets and atomic bombs, scientific and engineering marvels that popular memory had relegated solely to the pages of science fiction. Mainstream publishers cautiously added a select few science fiction titles to their lists, often atomic war speculations like Murray Leinster’s The Murder of the U.S.A. Published in 1946, it was discreetly peddled under his real name of Will F. Jenkins and called “A New Kind of Murder Mystery.”

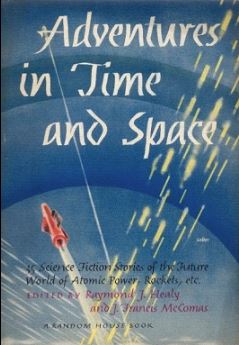

More influentially, two giant anthologies of science fiction were released in 1946, Random House’s 997-page Adventures in Time and Space, edited by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas, and Crown’s 785-page The Best of Science Fiction, edited by Groff Conklin and starting with an essay by Campbell, both heavy with Astounding stories. The spaceship was already the instantly recognized symbol of science fiction and would stay that way.

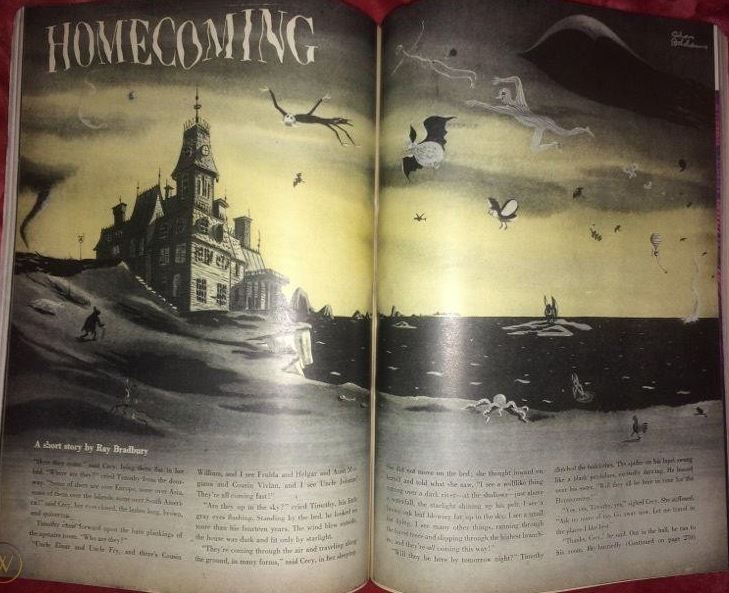

Commentators were forced to admit that the zanies may have been presciently warning the world for years. Mainstream magazines began to run articles cautiously praising science fiction, often turning to Campbell and making him the spokesman for the field. The New Yorker ran a short interview with Campbell, titled “Cassandra 1945,” just two years after their piece slamming the field, noting that Campbell had also just been interviewed by the Wall Street Journal on the economic meaning of atomic power.[4] A voracious reader of the slicks might see the occasional science fiction story as well, with Heinlein and Ray Bradbury (who actually appeared in Astounding a couple of times) placing stories in major magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Mademoiselle.

Still missing was what was available to authors in every other genre: publishing lines that were devoted to hardback books in that genre. Only hardback books were carried in bookstores, only hardback books were reviewed in newspapers and magazines, only hardback books were purchased by libraries. Original fiction published in magazines or, extremely rarely, in paperback, passed by without comment. Writers could look to those media for extra money or to gain recognition, but careers were built on hardback publication. No mainstream publisher saw science fiction as viable, not in hardback and not even in paperback, even if the somewhat more respectable fantasy genre was added.

Hardcore science fiction fans disagreed. They saw a niche opening begging to be filled. Two, in fact. A pent-up demand existed for original novels by favorite authors, many more books than could be handled in magazine serials and which might not be right for the dogmatic editors in the first place. Similarly, readers wanted those older serials in more permanent form. Magazines were ephemeral, quickly discarded and easily missed on newsstands. Science fiction fans were noted for amassing huge collections but the paper drives of the war depleted them, often while the fans were away in the military. Reprinting older novels, story series that could be recast as novels, and collections of stories in hardback would allow them permanent places on bookshelves as well as clearing the literary world’s bar for recognition. Anyone with access to piles of the last two decades of science fiction magazines had essentially a gold mine of material cheaply available and with a seemingly guaranteed audience, albeit tiny by mainstream standards.

One analogous publisher had been around since 1939: Arkham House, formed to reprint H. P. Lovecraft and others of his circle in unusual fiction. It did not release science fiction except in 1946 when van Vogt’s Slan, a 1940 Astounding serial, appeared. While Arkham formed the model that everybody would copy, the wannabes should have carefully noted that the line took many years to become successful. Worse, Slan received no reviews in either newspaper database I checked or in any professional genre magazine.

Nevertheless, the prospects looked bright and multitudes of fans jumped in to try their chances with fantasy and science fiction (f&sf) presses. Other than Gnome, 15 imprints started in the post-war 1940s: The Avalon Company, Buffalo Book Company, Carcosa House, Fantasy Fiction Field, Fantasy Press, Fantasy Publishing Co., Inc. (FPIC), Gorgon Press, The Grandon Company, Grant-Hadley-Enterprises, Griffin Publishing Company, Hadley Publishing Company, New Collectors’ Group, The New Era Company, Prime Press, and Shasta Publishers. What’s striking today about these names is the complete lack of the term “Science Fiction” or anything similarly technological, and the abundance of the word Fantasy and connotational terms like Griffin and Avalon. In the late 1940s, science fiction was subsumed under the broader term of fantasy. That would reverse, commercially and otherwise, by the 1950s. The sheer number of small presses saturated the market. (Only two very short-lived f&sf presses started in the 1950s. Those do not include the mainstream Greenberg: Publisher, which started in 1950 and put out 14 f&sf titles before petering out in 1956. No matter how many references make the claim, this firm had no connection to Martin Greenberg or Gnome. Nor did the much later Gibbering Gnome Press or gnOme Books.)

Only four of those fifteen would release even a half dozen titles – Fantasy Press, FPIC, Prime, and Shasta. The first two mostly brought out pre-Campbellian fiction; the latter two skewed more modern. Collectively, they published only a small fraction as much from the pages of Campbell magazines as Gnome did. I don’t believe it’s a coincidence that Gnome sold better and lasted longer than any of its competitors.

Allowing access to f&sf in hardback form – the other 15 publishers produced 65 books during the 1940s in addition to Gnome’s four – had the desired effect. Libraries became a major audience for sales. Mainstream bookstores carried the books and introduced them to a new audience. The Saturday Review of Literature and the New York Times Book Review inaugurated semi-regular review columns, with knowledgeable reviewers treating the books with respect. (Copying the thought processes that labelled The Murder of the U.S.A. as a murder mystery, the Times editors could find no other place to review the first Gnome book – a historic fantasy – except in the Criminal At Large mystery column. What readers thought of that is unknown. The quickly devised f&sf column ran under a procession of names, with most containing the epithet “Spaceman.”)

August Derleth started reviewing f&sf for the Madison [WI] Capital Times and Anthony Boucher did so for both the daily New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune. In 1949, The New Republic marveled at the sudden activity in f&sf, noting that “Five new publishers devoted to the genre have sprung into existence.” The writer’s imagination boggled that a “New York bookseller has a standing order from a Pittsburgh minister for every science-and-fantasy [sic] item that comes in; that a Pasadena manufacturer keeps his collection, which numbers about 2,000 volumes, in a concrete vault with four-foot walls; and that a drugstore in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, sells out 150 copies of Astounding Science Fiction, the leading magazine in the field, within three days of its publication each month.”[5] Time had ridiculed the genre in its July 10, 1939, issue, with “Publishers soon discovered another odd fact about their readers: They are exceptionally articulate. Most of these magazines have letters columns, in which readers appraise stories. Sample: “Gosh! Wow! Boy oh-boy!, and so forth and so on. Yesiree, yesiree, it’s the greatest in the land and the best that’s on the stand, and I do mean THRILLING WONDER STORIES, and especially that great, magnificent, glorious, most thrilling June issue of the mosta and the besta of science fiction magazines. . . .” A decade later they recanted, to give a respectful review of a Stanley G. Weinbaum collection in 1949, commenting generally that:

Several publishers estimate that from 30% to 40% of their readers are professional men, some of them scientists who read the stories for relaxation but with a sharp eye for scientific errors. …

There has been some speculation about the reasons for the science-fiction fad. The Saturday Review of Literature’s Harrison Smith has speculated about the relation of the “age of anxiety” to the “scientific fantasy story” as “a buffer against known and more conceivable terrors.” Publishers’ Weekly finds that the appeal of these stories lies “in their free flight of [imagination] . . . uninhibited by present reality, yet sometimes terrifyingly close to the advanced discoveries of modern science.”[6] [second ellipsis in original]

More publicity brought more readers which begat a dozen new magazines in the late 1940s and early 1950s, many of whom included book review columns that called readers’ attention to the spate of titles being offered. The turning point may have occurred in 1952, when Arthur C. Clarke, a well-liked insider whose books didn’t sell very well, saw his epic nonfiction tome The Exploration of Space picked up by the Book-of-the-Month Club. This national bestseller lifted all his earlier work to prominence and made him a superstar in fiction as well. His nova briefly outshone all other writers in the genre combined but in doing so spread light over the field as a whole.

After this success, all of Clarke’s fiction would be released by mainstream publishers, which at long last had begun to appreciate the value of a line of science fiction to hit the same markets that the small presses had opened. Clarke’s blockbuster, Childhood’s End, was issued in both hardback and paperback by newcomer Ballantine Books in 1953, as were classics like Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and The Space Merchants by Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth, and the first major anthology series of original stories, Star Science Fiction Stories, edited by Pohl. (The first original anthology, The Girl With The Hungry Eyes And Other Stories, was edited by the omnipresent Donald Wollheim and published by Avon Books in 1949. It made no lasting impression.) Except for the Bradbury book, all Ballantine covers were illustrated by Richard Powers, whose surrealistic designs are perhaps the best cover series in the history of the genre, although – or perhaps because – after the early years they contained no rocket ships or recognizable aliens. Ballantine cornered a large portion of the field the old-fashioned way: it offered advances of $5,000, about ten times what the small presses could afford.

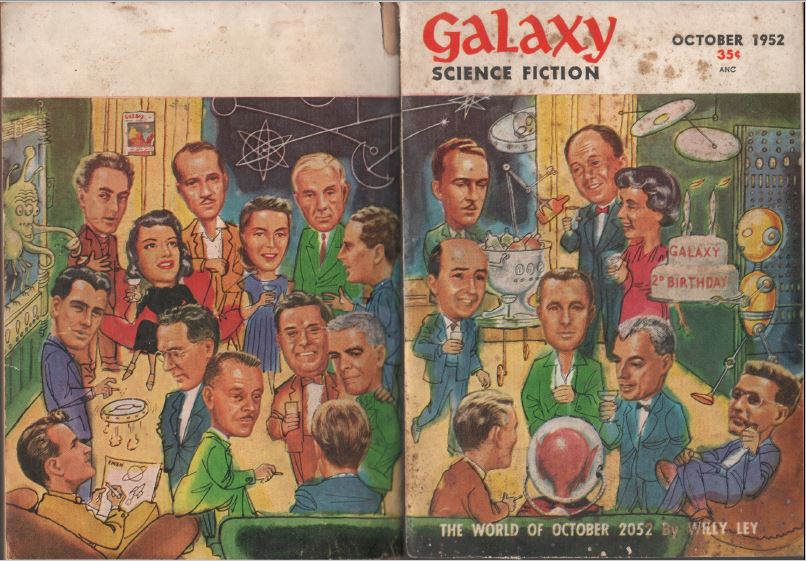

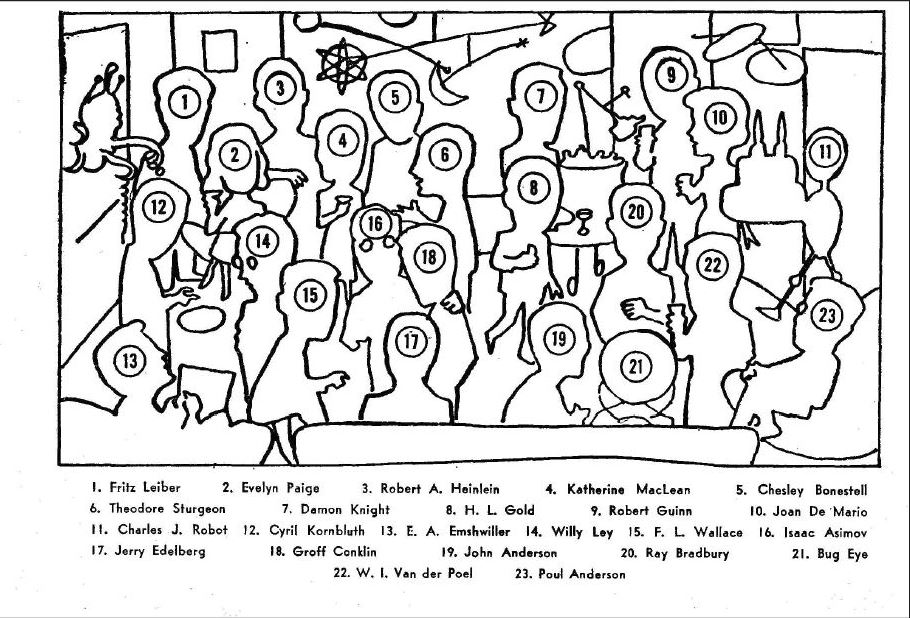

Campbell’s hegemony over science fiction got disrupted at almost the same time. Astounding never again produced a new superstar every few months as it had before the war. New names appeared – from 1946 through 1956, the magazine ran early works not just from Clarke but also from future Gnome writers Poul Anderson, Wilmar H. Shiras, F. L. Wallace, Mark Clifton, Everett B. Cole, Tom Godwin, James Gunn, Randall Garrett, and Robert Silverberg, as well as anthologist Judith Merril – but Astounding couldn’t claim them in the same way; none published more than a handful of stories there during Gnome’s life and several remain fairly obscure. Writers no longer needed publication by Campbell; they had a multitude of other magazines to write for and association with Campbell’s Astounding was not the plum it used to be. He now had true competition. The Magazine of Fantasy, which significantly became The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction with its second issue, and Galaxy Science Fiction debuted in 1949 and 1950 respectively and took over the field in the 1950s. They offered fans and, more importantly, writers, the opportunity to see a different kind of science fiction, bolder, freer, more literate, more sociological, tinged perhaps with a soupçon of sex. They were intimately in sync with their times in a way Campbell was not. Astounding retained much of its loyal fan base, but the new magazines opened the genre up at a critical time in its evolution.

(Time, curiously, did another reversal at this point. Reviewing the Galaxy Reader of Science Fiction in 1952, the anonymous reviewer julienned the genre. “The most striking feature of these stories, which are typical of most of the others in the book, is that they all seem to have been written by the same author. Except when they are wound up in a woolly snarl of technological jargon, they all employ one voice—that of the ’20s and ’30s tough guy, bounded on the rough side by ‘Huh,’ and on the smooth by slick patter [‘Her voice was like … a cello bowed up near the bridge’]. All the objects of numbed horror are interchangeable, whether they are masked women wearing steel talons on their fingertips or vaporous robots created by “molecular integrators” out of the vagaries of spacetime.”)[7]

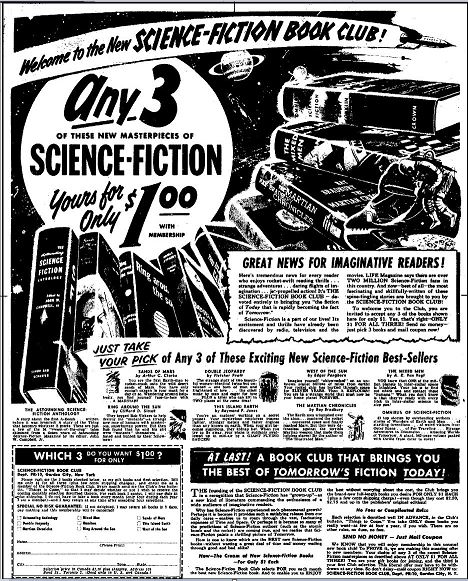

Another major change occurred when mainstream publishers slipped a few genre books into their lines. Simon & Schuster, Crown, and Frederick Fell all started doing so in the late 1940s. They published a few important books but didn’t change the field as much as the mainstream giant Doubleday did. The firm started dipping its toe into the field in 1946, although its early postwar titles were only tangentially related. The breakthrough came in 1950, when past and future Gnome writers like Nelson Bond, Isaac Asimov, and Hal Clement dominated its list, continuing in 1951 with the addition of L. Sprague de Camp, Fletcher Pratt, and Robert Heinlein. The killing blow was made in 1952, perhaps stimulated by Clarke, when Doubleday created a subsidiary company to release inexpensive reprints under the Science-Fiction Book Club (SFBC) banner. Doubleday had all the money in the world, compared to the small genre presses; its ads appeared in major newspapers and national magazines as well as the genre magazines. The full-page blaring ads caught the eye of seemingly everybody with an interest in science fiction, a lot of people at that point. The ads reported that “LIFE magazine says there are over TWO MILLION Science-Fiction fans in this country.”[8] (Back in 1943, The New Yorker had estimated only 250,000.)

Club members could take three books for one dollar when they joined and buy subsequent selections, a new one every month, for an additional dollar (plus shipping). (As a sign of the times, exactly two of the club’s first 50 offerings were from women. One was a Judith Merril anthology, the other a post-atomic war novel by mystery writer Theodora Du Bois. By comparison, eight of Gnome’s first 50 were written or co-written by women, preceding Merril’s four anthologies. (See The Women of Gnome Press.) Two of the nine 1953 selections were Gnome books, a rarity since Doubleday mostly reprinted its own titles. Fans of science fiction skewed young and therefore poor; the lure of cheap reading proved overwhelmingly tempting. Sales of the higher priced small press originals immediately fell off a cliff. The era of the small presses essentially ended like Bambi under the foot of Godzilla.

Answering the deliberately provocative question “Who Killed Science Fiction?” in 1960, bookseller Stephen Takacs put the blame squarely on the SFBC.

There is no science fiction field any longer. If I had stuck to selling science fiction during the past four years, I would have starved to death long ago. … I never see a young person anymore! … What is responsible? … Arrangements by which readers can purchase books for very small amounts in passable hard-covers. These readers have, [sic] since 1953 been people who do not ordinarily buy hard bound books, confining themselves to buying the magazines as they came out. When the change came to buy these bound editions they turned away in droves from the “fan” publishers like Shasta, Fantasy Press, Prime Press and Gnome Press. Bookshops during the past five years have “learned the ropes” and refuse to stock any hard bound science fiction.[9]

Oddly, the genre fell into the doldrums at this point of seeming mainstream success. The onslaught of presses and magazines oversaturated what was still a tiny niche market. The handful of top writers couldn’t produce enough product to fill two dozen magazines. Four young writers– Harlan Ellison, Henry Slesar, Robert Silverberg, and Randall Garrett – wrote a story a week each under a huge number of pseudonyms in the mid-to-late 1950s, driving the quality and variety of the fiction down. A major magazine distributor’s bankruptcy further decimated the already-weakened titles. Serious writers wanted to move over to full-length novels but the few publishers who were interested accepted no more than a small number of books, usually fewer than one a month, effectively locking all but the biggest names out of the market. Paperbacks reprinted titles rather than feature new books.

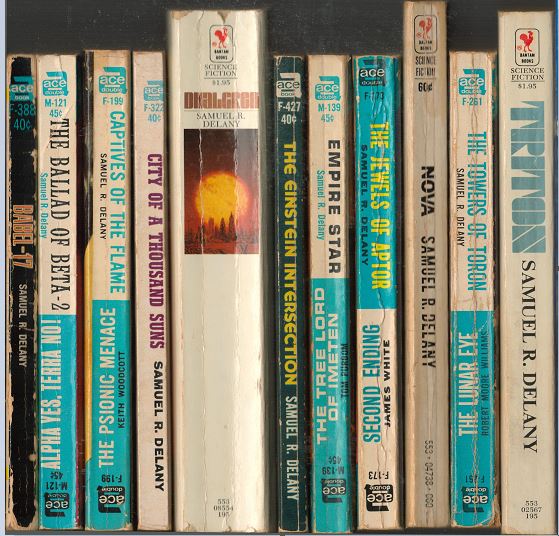

Ironically, a term that will pop up with grotesque frequency in the history of Gnome, that early 1960s low point which permanently crushed Gnome marked the beginning of the field’s greatest boom. A new generation of writers rivaling those of Campbell’s Golden Age started their careers in the 1960s. Paperback editors, led by Donald A. Wollheim at Ace, started accepting original books by younger writers and launched many to prominence. Ace and Ballantine both released J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy in paperback, which sold by the millions and was followed by an infinite number of imitators, eventually turning fantasy into a larger-selling field than science fiction. The Big Three of Clarke, Asimov, and Heinlein were made into hardback bestsellers by publishers who then reached back to re-release their entire oeuvres. Colleges, with Williamson and Gunn among the pioneers, started courses in science fiction, giving the genre a gloss of respectability that it badly needed. No more striking example of the change is evident than the career of Samuel R. Delany, who, starting in 1962, had seven short paperback novels published by Ace before he ever had a story in a magazine. In 1975, Bantam Books, with Pohl as editor, published his 879-page novel Dhalgren. A book longer than the entire Foundation trilogy published as a paperback original would have been unthinkable even a decade earlier let alone two or three. But it eventually sold a million copies. Campbell, if he were still alive, would have thrown a fit if he read the difficult, dirty, and literary text.

Campbell’s death in 1971 locked in his mythical status, one that is crucial to the understanding of Gnome and the coincident rise in respectability of science fiction after World War II. It is nowhere near hyperbole to say that from 1937 through 1950 Campbell essentially was the genre. He didn’t just rule science fiction, but also ran the premiere (and essentially only) fantasy magazine, Unknown, dependent on the same names he cultivated for Astounding. Only Amazing, its companion magazine Fantastic Adventures, and the decidedly third-rate post-Gernsback Thrilling Wonder Stories – all three aimed at younger and less-demanding audiences and taking scraps that Campbell rejected – managed to put out 12 issues in any year during that period, none of them consistently.

Campbell thereby rose to legendary status within the field by the time he was 30 and stayed at Astounding for another 30 years. Harry Harrison stated that “When I was 12 years old, I thought John Campbell was God”[10] and other authors independently echoed that praise. Thomas Disch, as far from a Campbellian author as the field offered, said, “It’s like BC and AD. In science fiction there’s Before Campbell and After Campbell. And it’s as clear a dividing line.”[11] The British iconoclast Brain Aldiss exuded similar superlatives: “For years on end, I was more faithful to Astounding than I was to any woman. I cannot understand the grip that that had on my adolescent mind.”[12] No other editor in the first half-century of the genre rivaled him in importance, dominance, or influence over the field, not even Gernsback. He almost single-handedly shaped the image of science fiction both inside the field and in the gaze of the mainstream, whenever it condescended to look at the science fiction genre.

The colossus that was Campbell had consequences for the field. Many writers owed him their careers. Few could cross him or defy his whims and crochets and opinions, of which he had many, some odious. He told writers what to write, down to giving them ideas, plotlines, and endings, and told writers what not to write, mainly any indication that humans weren’t the smartest, orneriest, and most perfect species in the universe, i.e., exactly his conception of himself. His narcissism and sense of infallibility would eventually doom him to irrelevance as he narrowed his conception of what science fiction was until only a few writers could follow his strictures, increasingly fatal when true competition stole his favorites in the 1950s.

Worse, he was emblematic of the American attitude that prevailed during World War II, that self-love that looked at the rest of the world with disdain and distrust. In 1973, fans created the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer to honor the man who found so many of the field’s young greats, and handed it out at the ceremonies for the Hugo Awards, named for Gernsback. The name lasted until 2019, when its winner, Jeannette Ng, accepted the award with a speech that led to its being renamed The Astounding Award for Best New Writer. Her acceptance speech started with this paragraph.

John W. Campbell, for whom this award was named, was a fascist. Through his editorial control of Astounding Science Fiction, he is responsible for setting a tone of science fiction that still haunts the genre to this day. Sterile. Male. White. Exalting in the ambitions of imperialists and colonisers, settlers and industrialists.[13]

Those harsh words closely define today’s perspective. (New Wave writer and editor Michael Moorcock has also called Campbell a fascist, for his views on slavery.[14]) Such sentiments would have startled and enraged most authors – most people – in the 1940s, of course. Of all the myriad of possible futures they imagined, this particular one was never offered, and probably inconceivable. From their viewpoint, they were progressives, writing clean and decent tales exalting expertise, knowledge, and the sane application of both. Their fiction was markedly less racist than the average genre story of the 1930s. Indeed, it is probably less likely to offend someone today than many contemporary mysteries, the genre that outsold every other type of fiction in the 1940s. If Campbell’s authors wrote stories about people who looked and thought like them one-upping all others they felt justified in doing so. The Depression went unsolved by all the usual experts and the world had plunged, once again, into a world-wide conflict. The Present that they wrote about and in was very much the one that Henry R. Luce dubbed The American Century in a 1941 prewar issue of Life. That essay called for the end of American isolationism and the imposition of American values on the world. The ensuing war was taken as proof that following that course was correct and had been proven a thousand times over, with the atomic bomb that ended the war considered the apotheosis of American technology, a problem-solving engineering feat far more impressive than those in Astounding stories. Campbell’s views might have shaped science fiction, yet they were but an echo of the prevailing sentiment among visionaries in the mainstream world, which shaped American culture as a whole. For perspective, it must be noted that today’s use of the word fascist, which might be applicable to Luce as well, has connotations that weren’t in the minds of those who lived in a world with true capital “F” Fascists out to eradicate those they considered outsiders and inferiors.

Many of the young writers that entered the field in the early 1960s deliberately countered the Campbellian mindset and the field as a whole joined the general cultural rebellion of the decade. The so-called New Wave did not completely displace the Old Guard, to be sure: a split in attitudes toward the war in Vietnam roiled the genre for years. Yet over time, both science and fantasy widened their outlooks and brought in millions of new readers of all types. In today’s publishing world, f&sf is a respected genre featuring something for everybody. If young adult works like the Harry Potter series are included, f&sf often dominates bestsellers lists. Modern award lists are replete with authors as varied as the competitors at an Olympics. Ironically, works that would be called science fiction if published in genre lines are now increasingly being released by mainstream houses although without the science fiction label. Books on the implications of artificial life, machinery taking over from humanity, and “cli-fi” – dystopian futures based on the ravages of climate change – are considered major works of mainstream social commentary just as the proto-science fiction of such writers as Wells and Cook were at the dawn of the 20th century.

The history of the field is not easily summarizable. The past includes numerous highs and all-too-many lows. The fiction comprises a large grouping of popular favorites which can at best be described as page turners and a smaller covey of literary brilliance. The authors sometimes thought they were writing for the ages and at other times speed-typing throwaway ephemera. The audience was often fanatically embracing and at times loudly excluding. The publishing community alternately shunned and embraced the label. Science fiction, fantasy, f&sf, is less of a Venn diagram than a Rorschach inkblot, much like all history is today.

However we look at the history of the genre from our – fleeting – perspective in the third decade of the 21st century – a time once thought so distant that works of the far future could be set there so that any inventions, any mores, any results might be believable – the time period from just before World War II through the Korean War was critical to establishing the field as it persisted for the next half century and more. The Gnome Press had an outsized role in that history, one that has never been more than casually recounted until now. Everything about the press serves as a microcosm of the larger forces that turned f&sf from a beleaguered and risible in-group to an auger of a frightening yet exhilarating future.

[1] H. H. Holmes [pseud. of Anthony Boucher], Rocket to the Morgue, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. 1942.

[2] “Inertrum, Neutronium, Chromaloy, P-P-P-Proot!,” The New Yorker, February 13, 1943, 42.

[3] Bernard DeVoto, “Doom Beyond Jupiter,” Harper’s Magazine, September 1939, 445-448.

[4] “1945 Cassandra,” The New Yorker, August 25, 1945, 15.

[5] Richard B. Herman, “Imagination Runs Wild,” New Republic, January 17, 1949.

[6] “Books: Never Too Old to Dream,” Time, May 30, 1949.

[7] “Horrors in Space,” Time, April 7, 1952.

[8] Parade Magazine, Oct. 18, 1953, 36

[9] Stephen Takacs, Safari Annual 1960, 90-91.

[10] John W. Campbell’s Golden Age of Science Fiction, Text Supplement to the DVD, by Eric Solstein and Gregory Moosnick.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] https://medium.com/@nettlefish/john-w-campbell-for-whom-this-award-was-named-was-a-fascist-f693323d3293. Ng notes that her original speech miscredited the magazine as Amazing.

[14] Solstein and Moosnick.