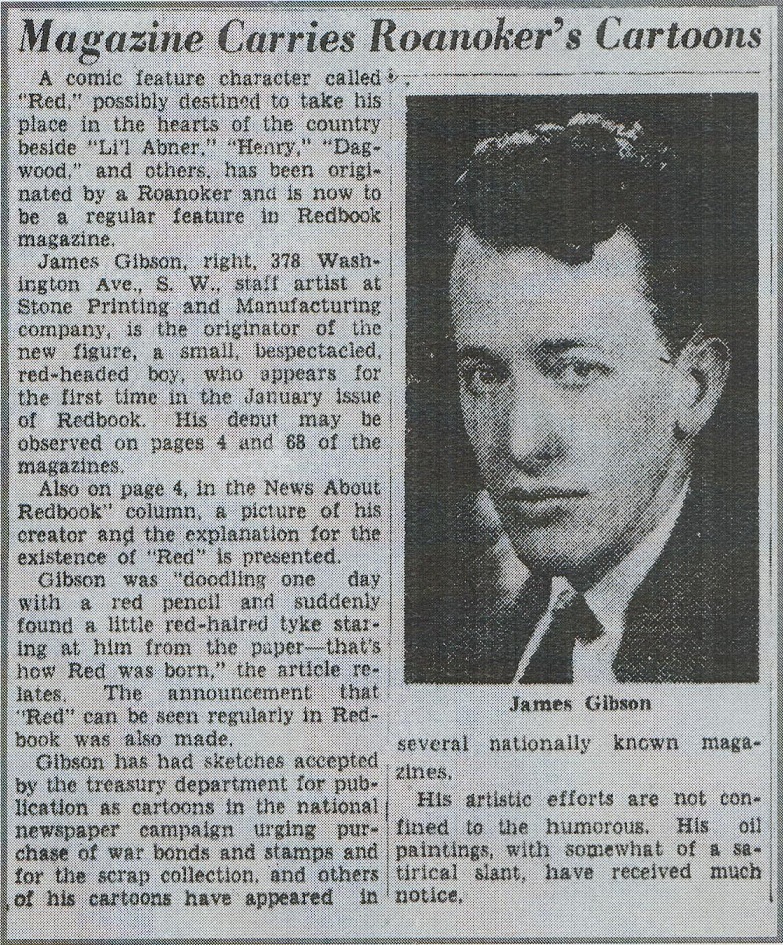

James Gibson

The Thirty-first of February (1949)

Comments

No biographical information is available on James Gibson in any database I could find. The ISFDB lists only two pieces of art by him, this Nelson Bond Gnome book and Exiles of Time, a 1949 book by… Nelson Bond. That left me wondering whether he had a personal connection to Bond. Bond lived in Roanoke, VA at the time so I searched for Roanoke artists.

Only a single, odd document was of any use, a scrapbook whose index of contents alone, almost all of newspaper clippings, could be found. Still, those headlines looked promising: Roanoker’s Painting Attracts Attention (James Gibson) – RWN 11/19/1941; Roanoke Artist’s Cartoons Helping Bond, Stamp Sales (James Gibson) – RWN 10/12/1942; Magazine Carries Roanoker’s Cartoons (James Gibson) – RWN 01/10/1944; Appealing Comic Book Published (Fred C. Hubbard, James Gibson, John Kessler, Russell L. Paxton) – 02/12/1950; Magazine Cites Roanoke Cartoonist (James Gibson) – 8/5/1956. Unfortunately, the RWN mentioned is likely the Roanoke World-News, a paper that newspaper databases skip many years of.

With those as a base, I found evidence of a James Gibson who appeared to be the same person, e.g., a brief note in the November 15, 1942, Bluefield [VA] Daily Telegraph that read, “James Gibson, of Roanoke, is winning national recognition as an artist. … The young man is a cartoonist. Two of his sketches have been approved by the United States treasury department for use in the publicity campaign urging the purchase of war bonds and stamps.” One of the few other papers in the database is, fortuitously, the January 10, 1944, issue with yields the only picture of the purported James Gibson on the Internet.

A James Gibson who was a cartoonist and comic book artist also pops out in searches. He is credited with the covers for several issues of the humor magazine Judge in 1945 and 1946. Similarly, a James Gibson co-illustrated a one-shot comic book called The Adventures of Flip and Chip: The Chipmunk Twins in 1949. It was published by the Paxton Press of Roanoke, so is almost certainly the “appealing” comic book mentioned above.

Finally, after much searching, the relevant newspaper page appeared. The Roanoke Times from February 27, 1949, carried definitive evidence. In an article headlined “Bond to Produce, Direct/Patchwork Air Theater,” mention is made of his forthcoming collection The Thirty-first of February. And the article ended with this:

Also adding interest locally is the fact that the dust jacket for the book was designed by James Gibson of Roanoke, whose cartoons sponsoring the local school bond drive are appearing currently in the local press.

Gotcha.

Harry Harrison

Tomorrow and Tomorrow/The Fairy Chessmen (1951)

Comments

Born Henry Maxwell Dempsey, but whose last name was changed by his father shortly after his birth, Harry Max Harrison (1925-2012) is far better known today as a writer, but started his career as an artist. His family moved incessantly during the Depression, so Harrison latched onto books and magazines. A copy of Amazing Stories led him into f&sf and at the age of 13 he became one of the founding members of the Queens chapter of the Science Fiction League founded by Hugo Gernsback. He started doing fanzine art while still in high school.

After the war, Harrison drifted into Manhattan’s Hogarth School of Art, which became the Cartoonists and Illustrator’s School, run by sometime Tarzan artist Burne Hogarth. Among a number of other soon-to-be-famous comic book artists, Harrison met – tiny world alert – future Gnome artist Wallace Wood. They teamed up for comic book work, swapping penciling and inking chores for dozens of titles from almost as many companies before breaking through to slightly better paid assignments for EC Comics.

Egos clashed by the end of the 1940s, and Harrison did some comics on his own along with a variety of editing and writing jobs. Along the way he became a member of the Hydra Club, a social group of the numerous f&sf pros living in and around New York, with admittance by invitation only. In fact, in his memoir Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!, he says that “I was still grinding out comics when I did a book jacket for Gnome Press. On the strength of this Marty [Greenberg] took me around to a Hydra meeting.” Tomorrow and Tomorrow/The Fairy Chessmen appeared in late 1951, though. By that time he had already been doing interior art for f&sf magazines for a full year. According to Paul Tomlinson, Harrison’s bibliographer, it was at the Hydra Club that Harrison got an assignment from Damon Knight, then editing Worlds Beyond. Harrison supplied most of the art for the three issues it lasted. The publication dates for those issues make it clear that the art had to be supplied in 1950. One of these timelines has to be wrong. Harrison must have been a regular at the Hydra Club by mid-1951 because he drew a cartoon of 40+ members to accompany an article by future Gnome anthologist Judith Merril in the November 1951 issue of Marvel Science Fiction. (see The History of Gnome) The caricatures give us possibly the best appreciation of the look and stature of the inner core of the field at the time and could only have been supplied by someone granted frequent attendance at the meetings. Unless Greenberg held the cover for over a year, it’s hard to credit Harrison’s account.

The cover for Tomorrow is the only one that Harrison is credited for in this period, and is frankly such an amateurish piece of fanzine-level art that it’s hard to image him getting more such assignments. Fortunately for him, his art career in f&sf was nearly over by the time the cover hit bookstores. While working on the art for Worlds Beyond, Harrison became too ill to properly hold his pen. In need of money, he laid a typewriter on his chest, pounded out a short story from his bed, and sold it to Knight for $100, far more than he made for art (all of five dollars per illustration) and with less time and effort. The dime dropped. Harrison started his transition to writer and made himself a major name that so overshadowed his art that today few remember his career began that way.

Mel Hunter

Star Bridge (1955)

Reprieve From Paradise (1955)

Comments

Another child of the 1920s, Milford Joseph Hunter III (1927-2004) followed a different pathway from most of his contemporaries. He was a self-taught illustrator, working nights after his job as a draftsman at Northrop Aircraft Corp. in California. Success did not come quickly. Except for a few interior illustrations in the Winter 1950 New Worlds, he didn’t break through until the February 1953 Galaxy, which featured one his spaceships on its cover. He moved to New York and got showered with assignments.

Hunter quickly became a favorite for his spaceships and alien landscapes, perfect fare for the space-happy fifties. His subjects overlapped Bonestell’s but Hunter was matte where Bonestell was gloss, and the two complemented rather than competed. Oddly, neither of Hunter’s covers for Gnome showed off his true talent; they foretell the designed rather than illustrated covers of Van der Poel.

Hunter would pick up four Hugo Best Artist nominations, mostly for a long series of covers for F&SF, before he left the field to concentrate on the technical and scientific art that brought him mainstream fame.

David Kyle

The Carnelian Cube (1948)

Conan the Conqueror 1950 (design with John Forte illustration)

Renaissance (1951)

Typewriter in the Sky and Fear (1951)

Foundation (1951)

The Sword of Conan (1952)

King Conan (1953)

Comments

As co-founder of Gnome, David Ackerman Kyle (1919-2016) gets his life story told in The Founders, but his art gets split off here. As a member of the seminal f&sf fan group The Futurians, his first art sales, in 1941 and 1942, were predominantly to magazines edited by fellow Futurians Frederick Pohl, Robert A. W. Lowndes, and Donald Wollheim. The illustrations generally featured detailed views of laboratories or cityscapes with a few slightly stiff people dwarfed by the onslaught on scratchboard lines. His art first appeared in Stirring Science Stories, February 1941, illustrating his own first story “Golden Nemesis,” the only fiction he published in that decade.

Kyle wisely stayed away from people in his Gnome covers, limiting them to tiny figures on two Conan covers, although these were quite good. He naturally designed the cover for the first Gnome book, The Carnelian Cube, not a smashing success, but did better with the soaring spaceships giving motion to the covers of Renaissance and Foundation.

Perhaps more important than any cover is that he established the look and feel of a Gnome book. Open the two books published from Fantasy Press plates, Vortex Blaster and Invaders from the Infinite, and the font and page designs look utterly different from any other Gnome volume, just as the two Talbot Mundy books printed off the original Appleton-Century plates, Tros of Samothrace and Purple Pirate, look like each other and are in no way similar to Fantasy Press or Gnome. His gnome, reading a book under the shelter of a toadstool, was the first try at a Gnome colophon, replaced but closely imitated by Edd Cartier’s more science fiction-y gnome on a book rocket. Kyle also established standards that linked together series of books (until Gnome finances required dropping any such frills). All of Greenberg’s early anthologies had similar cloth-backed spines and the Conan series retained a common design almost till the end. Kyle’s rendering of Robert A. Howard’s “map of the world of Conan” was reused on several of the Conan books as well, a design point much noticed in reviews.

His 40s amateur work and his short Gnome career are just about the entirety of Kyle as a professional artist. He was a fan’s fan for eight decades, though, and his name must appear in hundreds of fanzines over that period. No doubt many illustrations are waiting to be catalogued by researchers.

Stan Mack

Starman’s Quest (1958)

Comments

Stanley Mack (1936-) has exactly one entry in the ISFDB, the cover for Starman’s Quest. He would have been 22 at the time, probably just graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design. He is indeed the same Stan Mack who later became a famed cartoonist and author, chronicling the eccentricities of New Yorkers. In the 1970s he was suddenly everywhere, after starting as an art director at the New York Herald Tribune and gradually evolving a drawing style that was very different from the Gnome cover. Stan Mack’s Real-Life Funnies – “Guarantee, All Dialogue Is Reported Verbatim” – ran for twenty years in the Village Voice. The similar Stan Mack’s Outtakes – “Guarantee: All Dialogue Overheard” – skewered the workplace for a decade in Adweek. National Lampoon ran his “Mule’s Diner,” whose dialog would have been spoken by nobody in the real world. The first two strips were collected in books. More books followed, children’s picture books, cartoon American history, nonfiction for young readers. He’s still alive as of mid-2023 and active on Twitter.

He was willing to answer a few questions for me, presented verbatim from an email in his capital-free style.

i must have gotten that assignment five minutes after getting off the train. but still have a clear picture of the cover in my head. a black line drawing of starman with a bold blue second color against a white background.

exciting for a young budding illustrator, and a wake up call for a newby. i never got the art back and was never paid for it. and have not forgotten it.

sorry, i don’t know how i met the man who assigned it. in my memory, he was new york elegant, as was his apartment where we met. never saw the publisher’s office. van something. would your research have come across a vanderpohl?

That has to be W. I. van der Pohl, Jr., busily collecting promising and cheap young artists, all the cheaper if he could stiff them for their work. Mack also remembers selling van der Pohl an illustration for Galaxy, but a search through the magazines doesn’t find one so it may not have run.

Hubert Rogers

Gray Lensman (1961)

Comments

Reginald Hubert Rogers (1898-1982) was born and grew up in Canada. A high school teacher encouraged him to become an artist, introducing him to the school of Canadian artists now known as “The Group of Seven.” One of them, A. Y. Jackson, became his lifelong friend and mentor. After an underage stint in WWI, mostly as a staff assistant when they discovered his age, Rogers moved to the U.S. to take advantage of the greater opportunities there. In Boston he studied at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1925 he moved to New York City and studied with Dean Cornwell at the Art Students League. He soon found the pulp magazine world, his first cover appearing on the January 15, 1927 issue of the twice-monthly Adventure, then one of the premier fiction magazines. Adventure remained his main market, using more than 60 of his 80 pulp covers through 1938. (Rogers did six covers for Adventure in 1935, the year that the magazine serialized Talbot Mundy’s Purple Pirate, but none were on any of those issues.)

Street & Smith lured Rogers in 1939, when he appeared simultaneously on the covers of Street & Smith’s Wild West Weekly and the February Astounding. He instantly became John Campbell’s favorite artist, landing the cover for 32 more issues, including 28 in a row from 1940 to 1942, and dozens of illustrations before he left to do war work. (A few illustrations for Unknown were sprinkled in as well.) One of the highlights was Rogers’ third Astounding cover, October 1939. His portrait of Kimball Kinnison, the Gray Lensman, standing arms akimbo in front of gleaming futuristic apparatus, defined “stalwart” for a generation of pulp stories. The second world war took him away for five years, but he returned to Astounding in 1947 and added another two dozen covers and many interior illustrations over the next decade.

David Saunders at the online Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists, from which most of this biography comes from, quoted a Robert Heinlein anecdote I haven’t seen elsewhere. High among the many examples of the lowliness of pulp f&sf in the eyes of the mainstream is this anecdote.

“A Scribner’s editor asked me to suggest an artist for Rocket Ship Galileo. I suggested Hubert Rogers, [sic] She looked into the matter, then wrote me that Mr. Rogers’ name was ‘too closely associated with a rather cheap magazine,’ meaning Astounding Science Fiction. To prove her point she sent me tear sheets from the magazine. It so happened that the story she picked to send me was one of my own! I chuckled and said nothing. If she was only impressed by the fact that the stuff was printed on pulpwood paper, it was not my place to educate her. I wondered if she knew that my reputation had been gained in that same ‘cheap’ magazine. I concluded that she probably did not know and might not be willing to publish my stuff in Scribner’s had she known.”

The small presses had no such qualms. Rogers did the covers for three of Heinlein’s books with Shasta in the early 1950s. And Lloyd Eshbach of Fantasy Press decided to keep that October 1939 Astounding cover for his hardback edition of a misspelled Grey Lensman. The credits for Gnome’s reprint book read “Jacket Design by Hubert Rogers/Illustrations by Ric Binkley,” exactly the same as the Fantasy Press version. That should be clear enough, especially since the frontispiece is clearly signed “Ric Binkley” and the dust jacket cover is not. The ISFDB properly credits Rogers for the cover. Yet whoever wrote the ISFDB page for the Fantasy Press Grey Lensmen credits Binkley with the cover. This is clearly an error. To my eye, the Fantasy Press cover is identical to the Astounding cover except for minor shadings from the coloring process. Why pay an artist to duplicate a cover stroke by stroke when a reprint would be much cheaper? Why do so at a time when the original artist is very much active in the field and easily available?

So Hubert Rogers, who has no connection with Gnome otherwise, makes this list just as Chesley Bonestell did, by Greenberg using someone else’s ready art. The Gnome Press reprint of Gray Lensman, getting the spelling right, shrinks Rogers’ original cover and reduces the coloring to sepia without any other alteration that I can see. No Binkley at all.

Murray Tinkelman

This Fortress World (1955)

Comments

Murray Tinkelman (1933-2016) got his training at yet more of New York’s bottomless supply of art schools. The Brooklynite went to the High School of Industrial Art, and – after using some of his artistic talent in military service – came back to study at Cooper Union and finally at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. From there his career soared. Jane Frank, in her 2009 Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists of the Twentieth Century, claimed that he had “won more than one hundred fifty major art awards.” He did mountains of work in dozens of subjects and was a renowned teacher at several universities. Closer to home, he’s in Frank’s compendium mostly because of work from 1976 to 1981 for Del Rey/Ballantine.

His entry in the ISFDB for This Fortress World therefore looks like a misprint. No other work is cited until 1964. In 1955 he was still in school in Brooklyn. How he got to Gnome is another mystery. However, Frank reports that Tinkelman “was unhappy with the commercialism in galleries and instead decided to be an illustrator. His first published work in the SF genre was for the first issue of the short-lived magazine, Vortex.” Vortex, a seventh-rank zine (its contents pages listed “Jock Vance” and “Morion Z. Bradley”), started and ended in 1953. It packed 45 stories into its two issues. Three stories in the debut issue – “The Last Answer” by Bryce Walton, “The Honeymoon” by Charles E. Fritch, and “The Time Contraption” by Anthony Riker – are credited to “Tink” in the FictionMags Index, although the ISFDB credits F. Anton Reeds using the alias Anthony Riker for “The Time Contraption” and calls the other two “uncredited.” An interview late in his life drew forth memories:

I’m just a journeyman artist who is attracted to certain subject matter, and I do have a soft spot for science fiction. The first science fiction illustration I did was for Vortex, which lasted for just two issues. At three to five dollars for each illustration, I assure you I was overpaid,” Tinkelman said, smiling at the thought.

How he got to Gnome is unknown. Let’s hope it wasn’t lack of payment that drove him out of the field for years.

L. Robert Tschirky

Lost Continents (1954) (with Ric Binkley)

Comments

L. Robert Tschirky’s (1915-2003) first name is officially unknown and not given in any database. Jane Frank, in her 2009 Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists of the Twentieth Century, speculates that his name was Leopold, after his father. This is almost certainly correct. Tschirky graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1940 and Penn publications from 1938 and 1939 list a Leopold Robert Tschirky. The May 11, 1940, Philadelphia Inquirer has an engagement notice for a Leopold Robert Tschirky, a senior at Penn, and Jeannette Washburn Parker, who had graduated from Penn the previous year. Something interfered, possibly the war, in which he served in the Signal Corps, because his obituary states that he was “survived by his beloved wife of 60 years, Elenora Quinn Tschirky.” (Parker bounced back quickly. Newspapers have her engaged in 1941 and married in 1942.)

Tschirky later became an art director for the Encyclopedia Americana and a travel writer for The New York Times. He spent twelve years with Time-Life Books before retiring to Flagstaff, AZ.

Tschirky was a member of the PSFS, the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society, when members of the group decided to join in the rush to establish a small f&sf press after WWII. Frank says he was one of the four founding members of Prime Press, but ESHBACH lists their names and Tschirky isn’t one of them. No doubt though that he was heavily involved with the press because he’s credited with a half dozen covers for them from 1947 to 1950.

He was not a working professional artist then or later and has no other credits on the ISFDB except for Lost Continents.

That book was scheduled to appear from Prime but never made it to publication before the press collapsed. My speculation is that Greenberg picked up preliminary art from Tschirky as part of the package and that Ric Binkley incorporated it into his final design.

W. I. Van der Poel, Jr.

Interplanetary Hunter (1956) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”) (with Ed Emshwiller illustrations);

Coming Attractions (1957) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”)

SF:’57: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy (1957) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”)

They’d Rather Be Right (1957) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”)

SF:’58: The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction and Fantasy (1958) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”)

Tros of Samothrace (1958) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”) (with Lionel Dillon as Lionell Dillon)

The Path of Unreason (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”) (1958)

Purple Pirate (1959)

SF:’59: The Year’s Greatest Science-Fiction and Fantasy (1959)

The Dawning Light (1959)

The Bird of Time (1959)

The Menace From Earth (1959)

The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (1959)

Agent of Vega (1960)

The Vortex Blaster (1960)

Drunkard’s Walk (1961) (as by “W. I. Van der Poel”)

Invaders From the Infinite (1961)

The Philosophical Corps (1962)

Comments

Washington Irving van der Poel, Jr. (1909-1987) was a scion of a Dutch family that had lived in the New York area for hundreds of years. (Genre databases list his birthdate as July 27, 1908, but his obituary gives the date as 1909 and two separate newspapers state that he was 78 at the time of his death on October 29, 1987.) Born in Brooklyn, he moved with his family to the suburban village of Freeport in Nassau County, where his father, a newspaperman, became the mayor for eight years. Known as “Van” or “Irv” to friends, he married Priscilla Paine in Freeport in 1938.

He received a traditional artist’s education, attending Trinity College and the Art Students League in New York. He went to work for Time and Fortune magazines until the war started, which saw him used as a director of graphics and training aids for the Army.

Van der Poel was the art director for Galaxy Science Fiction magazine and the rest of Horace Gold’s projects, including Beyond Fantasy Fiction and the Galaxy Novel series, from the beginning. I know of no pictures of him, but he is the handsome Mad Man-type second from right at the bottom holding a martini glass on the cover of Galaxy’s 2nd anniversary issue, October 1952, drawn by Ed Emshwiller.

That seems apropos to his style. When Stan Mack got the call to submit artwork, he remembers: “in my memory, he was New York elegant, as was his apartment where we met.” Van der Poel is not known to have illustrated a single item for Galaxy nor does a search bring up any art he drew for the many other publication he worked as art director for. He designed rather than drew.

At some point in the 1950s, van der Poel doubled up as Gnome’s art director. From then on he actively sought out talented young artists and solicited their work for both Gold and Gnome. He brought in Stan Mack, Lionel Dillon, and Wallace Wood. They and he are credited for 27 of the last 29 Gnome covers. (The exceptions are the two books that recycled older art: Edd Cartier’s for Earthman’s Burden and Hubert Rogers’ for Gray Lensman.)

As Gnome sunk deeper into debt, Van der Poel couldn’t afford to hire even brand-new artists just out of school. Nor could Gnome afford the full-color art it once used to liven its dust jackets. Instead, Van der Poel used his skills to find clever ways to use shapes, outlines, and single-color washes to create arresting abstract designs.

In 1960, Van der Poel abruptly left Galaxy and apparently also left the f&sf genre when Gnome folded. He stayed an art director working for the New York State Conservationist and various technical journals like the Journal of the American Diabetes Association. He also left New York City, moving to noted art enclaves like Woodstock and Santa Fe. In the 1970s he moved to Missoula, MT, where he died in 1987. His son, Washington Irving Van der Poel III, stayed there to work as a geologist and environmentalist, a cause also promoted by his father.

Wallace Wood

Colonial Survey (1957)

The Return of Conan (1957)

The Shrouded Planet (1957)

The Survivors (1958)

Undersea City (1958)

Comments

Wallace Allan Wood (1927-1981) was known to millions as “Wally” but his friends called him “Woody,” which he preferred. Just barely old enough to spend time in the service at the end of WWII, he used the GI Bill to enroll the Minneapolis School of Art and then moved to New York in 1948 where he studied at the Hogarth School of Art. There he met and partnered with Harry Harrison, the two of them providing art for multiple comic books from their little studio. Jules Feiffer described it as “in a very slummy Upper West Side. It was an artist’s and writer’s ghetto. Just a huge room where the walls were knocked down, dark, smelly, roach-infested, and all these cartoonists and writers bent over their tables.”

One of the comic book companies was EC Comics. Wood and Harrison started with romance comics in 1949 but soon convinced owner Bill Gaines to publish Weird Science and Weird Fantasy, comic books that often adapted stories from the f&sf magazines. In 1952, he, along with fellow Hogarth students Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman, added on assignments for EC’s Mad, then a comic book. Wood’s panel-filling illustrations, with tiny jokes everywhere one looked, would run in Mad for more than a decade.

While today’s comic fanatics look at the early Mad as a pinnacle of the genre, Gaines paid so little that Wood supplemented his income with work for the same f&sf magazines he took stories from. Illustrations paid next to nothing but took less time than a dozen pages of panels and plenty of opportunities for cover art were available.

Wood contributed interior art to Planet Stories for a couple of years before, who else, W. I. Van der Poel got his hands on him. Starting in 1957, Wood did six covers for Galaxy Science Fiction, four covers for the Galaxy Science Fiction Novels series, and five covers for Gnome before 1960 rolled around. In and around those, dozens of interior illustrations appeared in Galaxy and later its sister magazine Worlds of If, until the end of the 1960s. Those earned him two Hugo nominations as Best Professional Artist in 1959 and 1960.